Imagine you have just read something about Servant of God Dorothy Day. Perhaps you recently rode a Staten Island ferry that bore her name. Maybe you saw Pope Francis’ message in a new edition of her first autobiography, From Union Square to Rome. (And yes, Day’s life was so eventful and significant that she has autobiographies, plural.) Where might you go to learn more about her and the Catholic Worker, the newspaper-cum-movement that she began?

Like hundreds of thousands of other 21st-century seekers, you might open a web browser and type in: “Dorothy Day” or “Catholic Worker.” If so, the first—sometimes second—site you would encounter would be CatholicWorker.org. You would be forgiven for thinking this is the movement’s “official” website. It is not. The site is the brainchild of one man—Jim Allaire—and it started, like the newspaper it’s named after, through relationships.

“That website is the most significant thing I’ve done with my life,” Allaire says.

Catholic Workers on the internet

Bringing the Worker to the internet was not a clear decision. The Catholic Worker is an anarchist, grassroots social movement; there are no central organizing committee, president, or, really, rules. There are certainly no membership cards.

Catholic Workers “are working for a Christian social order,” Day wrote in February 1940. The website, which, again, is not official, lists just under 200 Catholic Worker communities in existence today.

The New York Catholic Worker houses—where Day lived, worked, and died—still publish a print copy of the newspaper Day started in 1933. They still lay the paper out by hand, rather than in a digital program, according to managing editor Joanne Kennedy. And they don’t have a house website or an email—by choice. They have refrained from publishing a digital version of the newspaper.

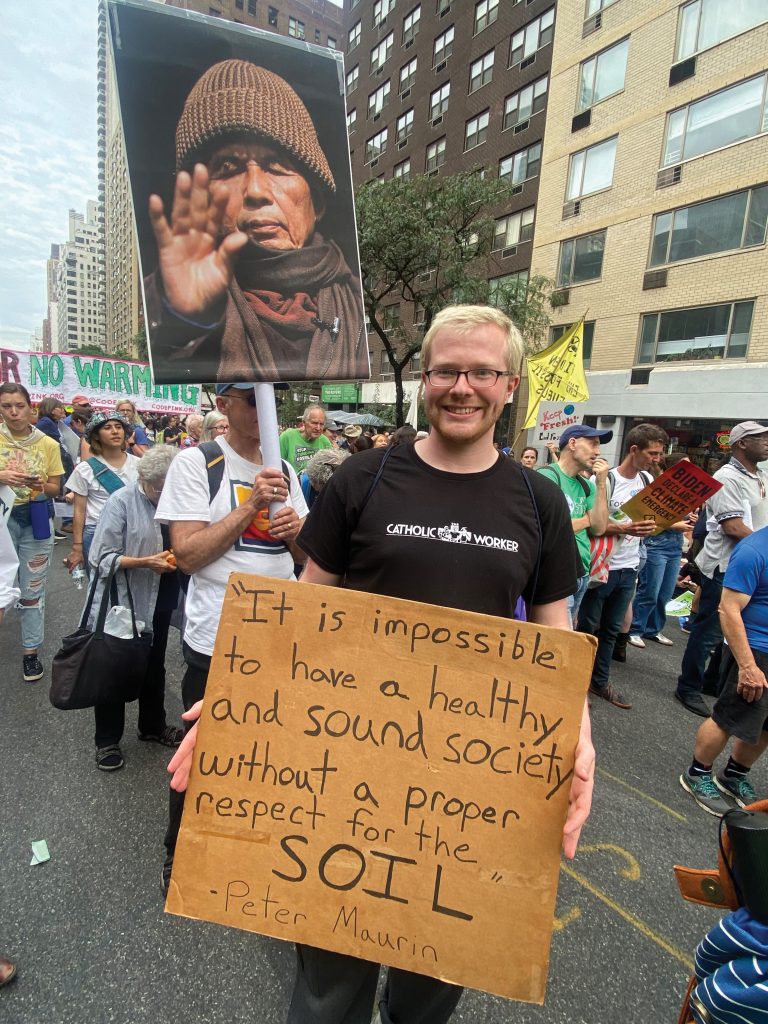

But one of the house’s newest and youngest members, Liam Myers, started an Instagram page for the house in October 2022. “With younger generations, the newspaper can’t be the only way that we share what we’re doing and what’s happening,” Myers says in a phone interview.

For folks out of state, Myers says, there’s no way to contact the house—and, crucially, subscribe to the newspaper—besides snail mail or the phone, “Younger people don’t love to pick up the phone and cold call someone,” Myers, 26, says. For many of Myers’ peers, their cell phones are their front porches.

Although the Instagram page now has more than 1,000 followers from all over the world, Myers says the impetus to start the page was local connection. Down the street from the Catholic Worker’s two houses in the East Village, Washington Square Park Mutual Aid operates, offering homeless folks in the neighborhood free food, clothing, and a beauty store. Spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic, mutual aid groups and community organizers advertised and connected with young neighbors over Instagram.

“I just felt that there’s this wealth of wisdom at the Catholic Worker houses—people who have been doing this work, which is very akin to mutual aid, for a long time—and I just really wanted to try to help foster those connections,” Myers says.

Worker houses’ Instagram presences have proliferated. Today at least 30 communities have profiles. The Day House in Detroit even has an account for their cats.

The New York house’s Instagram still thinks local, despite their global reach. They post Friday night meeting announcements, event invitations, and calls for soup kitchen volunteers; they also post messages for special days such as Day’s birthday and the anniversary of her death. They even encourage subscribing to the newspaper—yes, the real paper-and-ink one.

Myers was pleasantly surprised by the positive response to a call for subscriptions he shared on Instagram. He got 10 direct messages, a medium that is more accessible for the Instagram-scrolling crowd than a cold call might be.

Myers says he’s also fielded some skepticism from the community. “They ask, is this a good thing? Where’s the personalism?” he says. The Catholic Worker’s yearly “Aims and Means” refers to the “unbridled expansion of technology, necessary to capitalism and viewed as ‘progress,’ ” echoing Pope Francis’ skepticism of the “technocratic paradigm.” On the World Day of Peace last December, Pope Francis called for a global treaty on the use of artificial intelligence. “Technological developments that . . . aggravate inequalities and conflicts, can never count as true progress,” he said.

But one thing Myers learned was that the Catholic Worker—both the newspaper and the message—still holds appeal for younger generations. Myers just had to go to their digital space to invite them. “I’m doing this out of personalism,” Myers says. “Part of connecting with people is knowing where they are at.”

When the Catholic Worker distributed its first newspapers on May Day 1933 in Union Square, it was competing with communist tabloids and flyers. Now, with 76 percent of Gen-Z Americans on Instagram, the cell phone, not a park bench or hand-distributed flyers, is the most common entry point to the public exchange of ideas.

“Dorothy Day used the technology of her own time to get her message out—publishing newspapers and going to Union Square,” says Nathan Schneider, a professor of media studies at the University of Colorado Boulder and author of Governable Spaces: Democratic Design for Online Life (The University of California Press). “I can understand the urge to say no to the onslaught of internet technologies, but a lot of that comes out of not knowing there are other ways of engaging with the internet,” he adds.

Schneider, who became a friend of the New York Worker house when he was living in Brooklyn, hopes that the Catholic Worker can lead the movement to doing the internet on its terms: distributism, the common good, dignity of workers, and Catholic social teaching.

A key facet of the bourgeois mindset, according to personalist philosopher Emmanuel Mounier, is the prioritization of private goods—my house, my lawn, my car—rather than investment in the common good. The most popular technological infrastructures of the internet tend to promote, rather than challenge, our privatization and isolation.

As Elon Musk’s purchase and transformation of Twitter to X shows, social media is only as good as its owners. Schneider points out that people don’t feel they have power when they’re using platforms run by Big Tech such as Meta and Google—which are structured for shareholder profit rather than the common good of the community—but they don’t know any alternatives.

Simone Weil House in Portland, Oregon, hosted two talks last year about “Decommodifying Software” to help imagine what communitarian internet and technology look like. One of the points made was that the big tech companies use the same technology available to everyone, but we only access the technology by creating accounts with the tech firm. Mike Bass, one of the speakers at the Portland talks, compares free software—such as Firefox, Nextcloud, or May First Movement Technology—to a community garden. It’s accessible, and members can take personal responsibility for contributing labor; they can also build relationships with other neighbors in the garden.

“Digital resources are not infinite. You’re taught to think they are, and you’re taught to not think about managing them,” Schneider says. Invoking Leo XIII’s endorsement of distributism in Rerum Novarum (On Capital and Labor), he proposes: “But what if you thought of them as a commons that you comanage with other people?”

Personalism on the internet

When Peter Maurin, a French teacher who came from a poor farming family, wanted to start a newspaper for the workers of the United States, he went to Day at the recommendation of Commonweal’s editor, George Shuster. Maurin had become familiar with the workers of America while spending most of his 30s traveling around the country working in coal mines, on farms, and as a janitor.

He introduced Day to the philosophy of Mounier and other French personalists, who rejected the cruelty of industrial capitalism, the individualistic bourgeois search for comfort, and the systemic materialism of communism. Here was the distinctly Catholic social program and theory of change Day had been seeking since her conversion.

Maurin formulated “Easy Essays” to succinctly communicate complex theological, historical, and philosophical ideas. With Day’s encouragement, he wrote them down and published them as short, easy-to-remember, blank-verse poems.

Despite his commitment to poverty, simplicity, and eating local, Maurin would never scorn a global bullhorn like the internet. “If somebody told Peter Maurin that there was a way to communicate with everyone in the world, he would say: ‘Let’s do it,’ ” Joe Zarrella, a Catholic Worker who knew Maurin well, once told Allaire.

Allaire, now 82, read the Catholic Worker as a college student. In 1992, he and his wife, Barbara, opened a Catholic Worker house in Winona, Minnesota, on the Mississippi River with their friend Mary Farrell.

Allaire’s sons—“tech guys,” as he calls them, who went on to invent ColdFusion, a program that rapidly connects databases to HTML webpages used by Fortune 500 companies—had helped get Noam Chomsky’s writings on the internet. Allaire began thinking of how to make Day’s writings more accessible to researchers, writers, or anyone flocking to the internet. His sons helped their dad figure out how to make an online database for Day’s writings.

Before Allaire went live with the site, he wanted to take the pulse of the wider Catholic Worker community. At a regional gathering in Iowa, he shared his plan for a digital repository, and many of his fellow Workers around the country logged their objections. They pointed out that technology furthered the advances of the state into daily life and promoted mechanistic rather than interpersonal communication. They also noted the military roots of many contemporary technologies.

Marshall McLuhan, a Catholic Canadian media theorist, would support the arguments of technoskeptic Catholic Workers. According to McLuhan, all human invention extends from some bodily faculty: walking, hearing, or even thinking. The invention of certain technologies, McLuhan believed, exponentially magnifies that power—whether of communication, movement, or thought—and so eventually numbs the physical faculty on which it was originally based. We depend on the machine, he says, and then we become its servant. McLuhan’s theory suggests that the Catholic Worker’s personalist, arts-and-crafts philosophy of labor, which prizes handiwork and manual labor rather than automation, could not be compatible with the de-personalized world of the internet.

Undaunted, Allaire sent a circular letter in 1995 to the communities that had objected to his project. He also enlisted support for his Catholic Worker website from personalist Emmanuel Mounier. Mounier argues that technology is a neutral field of action; it can be used for ill but can also be used for good by well-informed users. Moreover, says Mounier, it ought to be used, since engagement in the world is the “essential imperative of personalism.”

Ultimately, Catholic Worker philosophy dictated that Allaire’s personal initiative should be respected. “Don’t keep beating on Jim Allaire,” he remembers Catholic Worker Karl Meyer saying. “We’re anarchists, we can do what we want.” Jim Forest and Tom Cornell, former managing editors of the Catholic Worker along with Day, also supported Allaire’s site. And thus, the movement’s digital front porch was created, and CatholicWorker.org was born.

Anne Fullerton, a Catholic Worker in the Washington, D.C. community, was also beginning her own website at about the same time, and she and Allaire presented their work in 1997 at the centenary celebration of Day’s birth. She and Allaire collaborated, and eventually she shut hers down and gave her materials over to CatholicWorker.org.

Soon after Fullerton and Allaire launched their sites, Mark and Louise Zwick at the Houston Catholic Worker put up a website with the help of their son, Joachim. This one was bilingual, like their newspaper, which was published in English and Spanish. And that was the Catholic Worker’s dot-com bubble.

As social media sounded a drawn-out death knell for the print newspaper, the Worker migrated more and more to the digital realm. “Even newspapers are hardly in the business of printing newspapers,” Theo Kayser, of the St. Louis Catholic Worker, says. Today, although the New York Catholic Worker continues to print the paper, other houses distribute their newsletters and papers digitally.

Sharing news to connect houses in the movement was one function of the Catholic Worker that moved online. In 2006, a Google Group began to pass along digital newsletters from different houses of hospitality. It shared news clippings and bore a strong resemblance to the back pages of the early editions of the Catholic Worker, full of letters and updates from different communities across the country.

Other sites have also brought the Catholic Worker newspaper to the internet. In 2019, the Catholic News Archive digitized all but the first 10 years of Day’s paper. In 2023, the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University digitized all the papers online.

Personalist internet 2.0

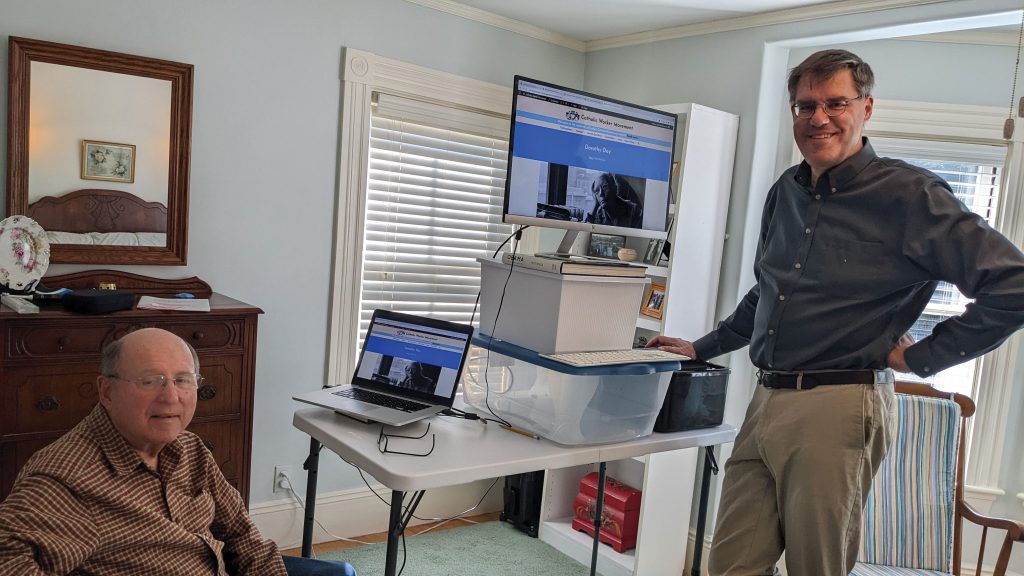

For its first two decades of life, CatholicWorker.org kept a very first-gen internet look. Its blue banner with pictures of Day and Maurin greeted the reader on the first page, and it remained unchanged until November 3, 2022, when the site’s new design went live.

Jerry Windley-Daoust, who took over webmaster duties from Allaire earlier that year, wanted to give the website the digital equivalent of a fresh coat of paint. This was just a small sign giving the workhorse site its due. After all, Windley-Daoust notes, the internet is often the first place a curious seeker may go to find a Catholic Worker house or read more about Day. More than one Worker has found the movement by googling “homeless shelter” or “soup kitchen near me.”

Windley-Daoust first met Allaire around the time Allaire launched his website, when Jerry and his wife moved into the Dan Corcoran Catholic Worker house in Winona, where Allaire and his wife, Barb, were also residing. Windley-Daoust, a journalist, author, and father of five, was “up to his eyeballs,” according to Allaire, when Allaire asked him if he was interested in taking over the webmaster duties. But he was absolutely interested.

One of the most important features of the site is its directory of Catholic Worker houses. In the beginning, very few communities were online, but now, Windley-Daoust says, about 90 percent of the houses have a website or Facebook page.

He’s created a system where houses can update their listing digitally, rather than sending in a postcard, in order to encourage communities to keep their listings up to date with accurate contact information. (Phone numbers that go nowhere and cluttered inboxes are a common bugbear in Worker houses.) “Phone books have been replaced by the internet now—and this is like the movement’s listing,” Windley-Daoust says.

In his redesign of the website, which launched in November 2023, Windley-Daoust’s goal was to make this website evolve from a static archive and phone book into a digital front porch that welcomes the curious and helps them learn about what the movement is doing near them today.

When Windley-Daoust took over the website in the fall of 2023, it received about 8,000 unique visitors every month. Now, he says, he anticipates more than 100,000 visitors to the site each year (they are already getting 10,000 a month). He has assembled a team of volunteers to write news about the communities’ activities. In January 2024, he launched an online newsletter for the site, Roundtable, which shares Catholic Worker communities’ stories and updates.

Spiritual works

“Peter Maurin used to go to Union Square and argue about politics, now people argue on Twitter,” says Theo Kayser, a Catholic Worker from St. Louis.

Kayser, 34, spent the past two years as a “nomadic Catholic Worker” before returning to St. Louis, where he had originally met the movement as a student at Chaminade High School in St. Louis. After graduation, he found the Los Angeles Catholic Worker through—surprise, surprise—searching online and finding a listing at CatholicWorker.org.

Kayser is one of the moderators for a Catholic Worker Facebook group dedicated to discussion of the Catholic Worker (think subreddit-like relationships, with tight, on-topic moderation). He began curating the group about four years ago, when he realized people on Facebook were looking for a place to meet and chat about the Catholic Worker but found the current options disorganized and unhelpful.

“People are looking for the Catholic Worker in these spaces and not finding it,” he says. Since then, the membership of the group has grown from 2,000 to 8,000. Kayser also has his own Instagram and Facebook presence, in which he regularly shares Day’s quotes in the form of memes.

In November 2022, Kayser and Lydia Wong, a Chicago Catholic Worker, also started their own podcast, Coffee with Catholic Workers. They interviewed Workers young and old, highlighting the voices and experiences of a diverse movement. Kayser has taken the Worker’s communicative message seriously. “Dorothy repeatedly refers to it as a media organization,” Kayser says.

Nevertheless, he has encountered plenty of older Workers who are skeptical about the Catholic Worker having a social media presence. And he does agree, to a certain extent, about the dangers of becoming “too online.” “The Worker is something to be lived and experienced in the real world,” he says. When we put our bodies on the soup line, listen to a recurring guest tell the same old story about the same problem, or hold a conversation and space in our hearts for the same people in our community over and over again, we ground ourselves in the harsh and dreadful reality of active love. We “touch grass,” as online denizens say.

Kayser points out, though, that in Peter Maurin’s original idea, houses of hospitality were for unemployed college students. Through action and clarification of thought, the scholars would become Workers, and Workers would become scholars. These Worker-scholars could create an economy based on the Catholic principles of personalists such as Mounier, organized around the health of the community, rather than healthy profits for shareholders or the priorities of the state.

As Dorothy Day wrote in the Catholic Worker in June 1946, “What we would like to do is change the world—make it a little simpler for people to feed, clothe and shelter themselves as God intended them to do.” And so, she continued, even the smallest of actions can make a difference. “We can throw our pebble in the pond and be confident that its ever-widening circle will reach around the world.”

The Catholic Worker, both the newspaper and its movement, was designed as a place to practice the works of mercy: for the body, through hospitality, and for the spirit, through “clarification of thought,” as Maurin would say. Spiritual works of mercy—to instruct the ignorant, counsel the doubtful, admonish the sinner, and comfort the sorrowful—do not always attract headlines, but they are at the heart of the Catholic Worker.

“The corporal works of mercy are obvious once you see them. The things about the spiritual works of mercy—the paper, the talks, the books written—is that you don’t often see the results,” Allaire says. But their effects, although invisible, are often tangible. “People find out about the Worker on the web, and pretty soon they’re hanging around one,” he says.

This article also appears in the March 2024 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 89, No. 3, pages 10-15). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Header image: Renée Roden

Add comment