The authors of Catholic Social Teaching: Our Best Kept Secret (Orbis) lament that contemporary college students, seminarians, and people in the pews know very little about Catholic teachings on social justice. Indeed, many Catholics refer to Catholic social teaching as the “church’s best-kept secret.”

I don’t know who coined this “best-kept secret” line, but I don’t buy it. Sure, many U.S. Catholics can’t define Catholic social teaching—but is it really the best Catholic case for social justice? Is it even a secret? When I hear people complain about the neglect of Catholic social teaching, I often think they should be more worried about the church’s suppression of liberation theology.

Liberation theology is a movement in Christian theology that arose in the 1960s and ’70s. It emphasizes liberation from oppression as the anticipation of ultimate salvation, arguing that poor and oppressed people can interpret scripture through their own experiences.

One example is Ernesto Cardenal’s The Gospel in Solentiname (Wipf & Stock). In this classic of liberation theology, Cardenal records the insights of Nicaraguan peasants as they discuss scripture during a time of dictatorship. Their authority comes from their lives, not from theological training, priests, or popes. The Nicaraguan people talk about corrupt government officials and greedy capitalists who threaten their well-being, but their concerns are spiritual as well as political. They point to the text and say, “Look, Jesus says this is wrong, too.” By talking to one another and bringing scripture into the conversation, people in this marginalized community realize that God is on their side.

Catholic social teaching, on the other hand, has the papal seal of approval—literally. It is the church hierarchy’s body of teaching on social, economic, political, and cultural matters. The hierarchy claims the authority to interpret God’s word in the world and to explain it to laypeople. The texts of Catholic social teaching include papal encyclicals, bishops’ pastoral letters, and documents from councils.

Modern Catholic social teaching dates to 1891, when Pope Leo XIII issued Rerum Novarum (On Capital and Labor), an encyclical that condemned inhumane labor conditions. Rerum Novarum is a touchstone for the Catholic Worker movement and others concerned with labor. Although it was a big step for the modern papacy, it was reactive in many ways. The Vatican disapproved of rising socialism and needed an alternative for disaffected working people. Rerum Novarum attempts a “third way,” a Catholic alternative to both capitalism and socialism.

Twentieth-century encyclicals touch on everything from war to interfaith relations. Despite the impact of many social encyclicals, they are not household names. Nevertheless, Americans of every religion do know about Catholic social teaching. They may not know the name Humanae Vitae, the 1968 encyclical that prohibits contraception, but they know that the Catholic hierarchy opposes birth control and abortion on moral grounds.

If most Americans don’t know about the content of Laudato Si’ (On Care for Our Common Home) or Rerum Novarum, it’s because many church leaders do not center those documents in their rhetoric or political action. The word secret is too innocent, and it’s misleading. The Catholic hierarchy prioritizes some parts of Catholic social teaching and neglects others. Meanwhile, many Catholics emphasize their preferred aspects of Catholic social teaching and ignore the rest.

St. Pope John Paul II visited Nicaragua in 1983. A few years prior, the revolutionary Sandinista party had overthrown a U.S.-backed dictator. The country was on the verge of civil war, with the U.S.-backed Contras poised to fight the Sandinistas for control. Cardenal was a priest, poet, Marxist, and, in violation of canon law, the minister of culture in the Sandinista government. He went to the airport to greet the pope, but when he knelt to kiss St. Pope John Paul II’s hand and receive a blessing, the pope withdrew. In a photo seen around the world, St. Pope John Paul II wags a finger, scolding the priest. The following year, the pope suspended Cardenal’s priesthood.

St. Pope John Paul II was far from the only opponent of liberation theology. According to Catholic Answers, liberation theology “distorts the Gospel message from one of salvation and transformation to mere social work.” Other critics go further, arguing that it is a Marxist threat to the integrity of the church. Outside Catholicism, Ronald Reagan’s foreign policy framed liberation theology as a “weapon against private property and productive capitalism.” Ultimately, many proponents of liberation theology were murdered because they threatened oppressive regimes.

Liberation theology, unlike Catholic social teaching, is populist—of the people. To be sure, it is often mediated by academic theologians, and many of its founders were men. Liberation theology and Catholic social teaching are not entirely separate, either: There has been major cross-pollination, for instance, through the 1968 Medellin conference, a meeting of the Latin American bishops after the Second Vatican Council.

Yet they diverge, because liberation theology moves authority from the Vatican to the streets. This threatens the hierarchical structure of the church. Catholic opponents of liberation theology do not see the church as a movement community of poor and oppressed people. By contrast, liberation theology sees the church as a people working for their spiritual and material liberation. The people do this by identifying with Jesus and emulating him in their own context.

For Black liberation theologians, identifying Jesus with Black people in the United States bolsters resistance to segregation and state violence. For the Nicaraguans in Solentiname, identifying with Jesus meant comparing King Herod to the dictator Anastasio Somoza.

Liberation theologies address all sorts of people and experiences. Liberation theologies can be queer, womanist, feminist, Dalit, mujerista, and much more. Christians ascribe to shared truths, but we understand those truths through experience, context, tradition, and conscience. European men have led the Roman Catholic Church for nearly two millennia, and they’ve tended to treat their context as universal. They have colonized the world to impose their truth.

The question of authority is the heart of the difference between liberation theology and Catholic social teaching. Who has the greatest authority to interpret scripture and tradition? The magisterium of the Catholic Church grants different levels of authority to different people; famously, the pope reaches the highest level when he speaks ex cathedra. Liberation theology operates outside this structure. It transcends Christian denominations. It elevates the marginalized people whom Jesus befriended. It can be unpredictable, subjective, and anticlerical. Church leaders call it heretical, because it threatens their power. It contradicts their understanding of what the church is and who it is for.

When Catholics want to center social justice without critiquing the power structure of their church, Catholic social teaching is their best bet. Elements of Catholic social teaching challenge hierarchical power structures, but the teaching still derives authority from the Catholic magisterium. Many parishes have Laudato Si’ study groups and committees, but few offer groups about liberation theology. Liberation theology is too controversial, too ecumenical, and too uncomfortable. Some people treat it like an embarrassing family secret.

Forty years after St. Pope John Paul II wagged a finger at Cardenal, church hierarchy has made slow, quiet concessions to Cardenal’s movement. Several years before Cardenal died, Pope Francis reinstated his priesthood. Although no great champion of liberation theology, Pope Francis is more open, lacking the anticommunist zeal of his predecessors. The times are changing, and not just because the Red Scare has died down. I think today’s church hierarchy perceives liberation theology not as a threat but as irrelevant. Decades of neoliberalism and suppression have taken their toll.

In 2019, commenting on his warm collaboration with Gustavo Gutiérrez, Pope Francis said, “Today we old people laugh about how worried we were about liberation theology.” This line makes me sad, because the church hierarchy should be worried about liberation theology. Liberation theology threatens power structures. If more people took it seriously, they would start to dismantle those structures.

Catholics who want profound change in their church and world should look to liberation theology. When laypeople reclaim liberation theology, we reclaim our own authority as the church.

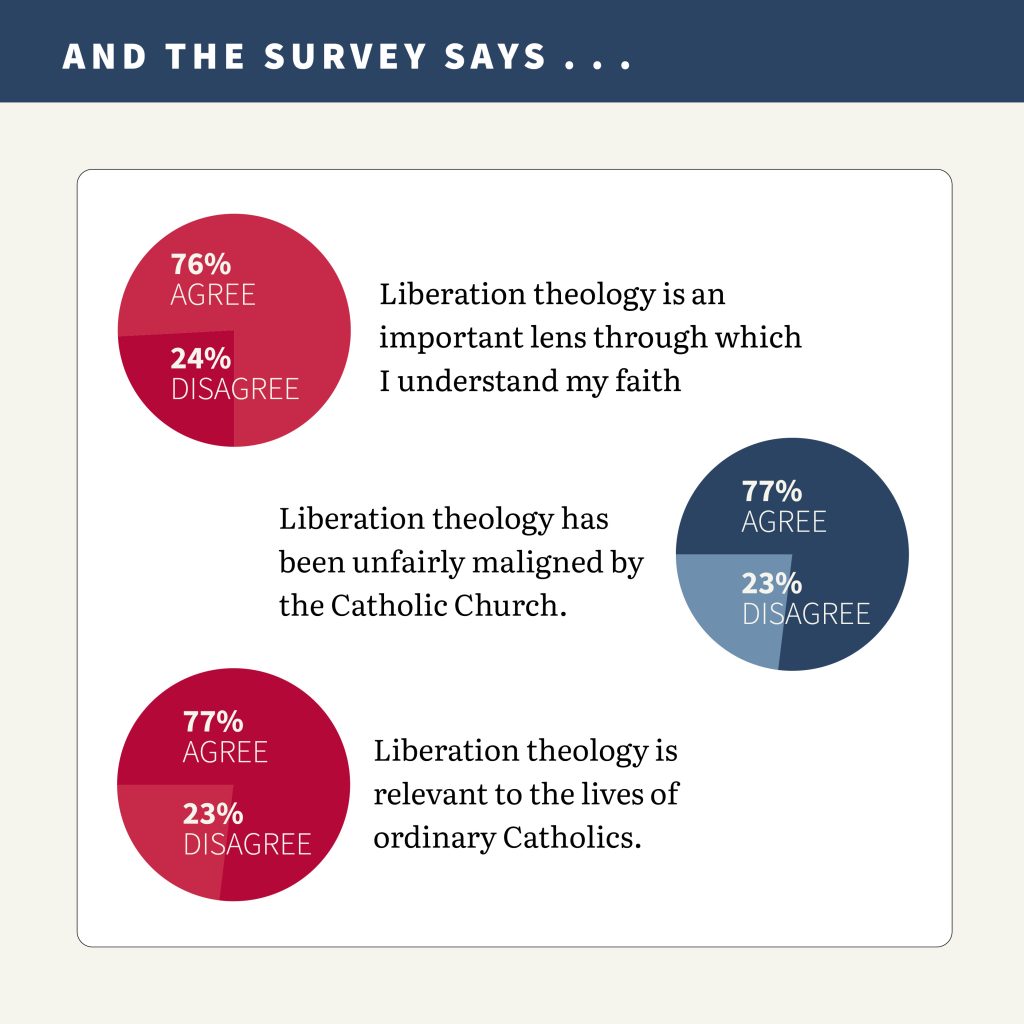

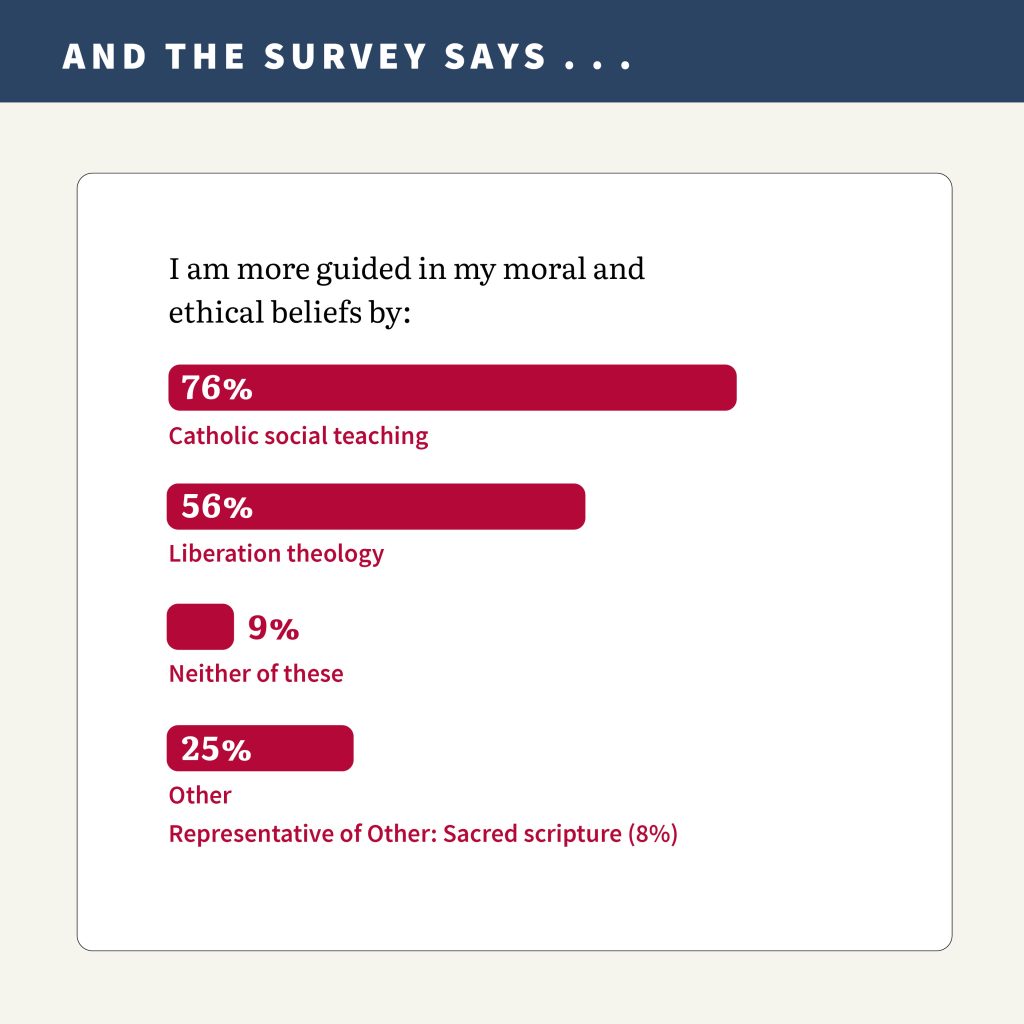

Results are based on survey responses from 79 uscatholic.org visitors.

This article also appears in the January 2024 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 89, No. 1, pages 21-25). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Fuego he venido a traer a la tierra, Maximino Cerezo Barredo

Add comment