One night, I came home late from work and took off my shoes at the door, as is my family’s custom. Walking in barefoot, I stepped on my son’s Legos that had been left out and cried out in pain: “Jesus Christ!”

Vocal responses like this are what many of us think about when we hear “do not take God’s name in vain.” But this is a long-held misunderstanding of the verses in question, Exodus 20:7 and Deuteronomy 5:11. These verses are not concerned with individual swearing as much as publicly misrepresenting who God is.

To understand this, there are several things to keep in mind. The first is literary context. In the Exodus narrative, God, through Moses, offers the Hebrews not only “freedom from” the oppression of enslavement but also an interconnected “freedom to” become a new people who will carry God’s saving presence to all others. This invitation and its acceptance are the covenant, through which is born Israel, the Jewish people. The Ten Commandments are part of the ethics and spirituality of this ongoing covenant.

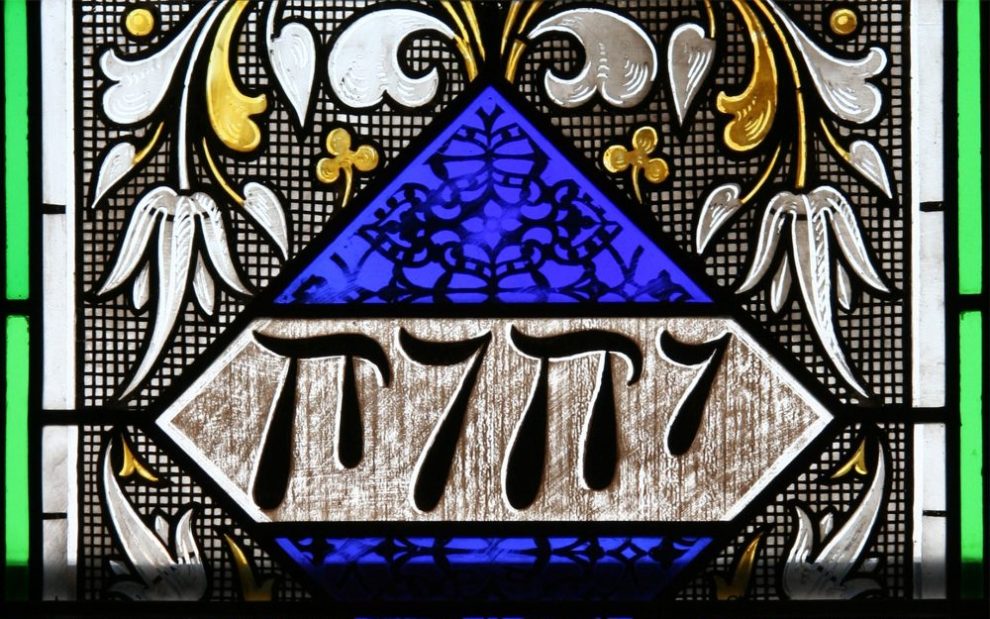

The second thing to keep in mind is the Hebrew word that often is translated as “take.” Its root, nasa’, carries a wider web of meanings that include: “to lift,” “to carry,” “to bear,” and “to take away.” It is a verb that connotes physical action such as lifting up God’s name and carrying it with you for all to see.

So a better understanding of this commandment may be “do not carry the Lord’s name in vain.” This has little to do with a moment of verbal weakness when overwhelmed by emotions or pain. Rather, it is a warning about putting God’s name and approval on anything violent and harmful to our fellow creatures. It is carrying God’s name and claiming God’s approval for war, injustice, dehumanization, and the desecration of creation. It is an attempted domestication of God’s spirit of limitless love, justice, and compassion to fit our limited human understandings.

When teaching, I often tell my students that the easiest way Christians have tried to justify that which is horrifying—enslavement of African peoples, violence against our Jewish and Muslim siblings, the dehumanization of women, genocide against Indigenous peoples, intolerance toward LGBTQ people, exploitation of the Earth—is by placing that so-called justification into the mouth of God. Then Christian leaders wash their hands of responsibility—just as Pontius Pilate did when he had Jesus executed as an enemy of the empire, though he knew Jesus was innocent—and claim there is nothing they can do because it is “God’s plan” or “God’s word” or because “God wills it.”

The second commandment warns against such dangerous hubris. The commandment not to take God’s name in vain reminds us that our words, beliefs, actions, and habits reflect an understanding of God to others. And the Spirit desires that we testify to a God of life, not a god of death.

This article also appears in the September 2023 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 88, No. 9, page 49). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Add comment