In 2022, when Pope Francis canonized St. Titus Brandsma, all I knew about the saint was that he was a Carmelite friar who was murdered at the Dachau concentration camp. Now, having read several biographies of Brandsma, I realize I have another heavenly spiritual director to inspire me. Like Dorothy Day, St. Titus was a journalist who preached gospel love in the face of evil. He now joins St. Francis de Sales as the patron saint of journalists. St. Titus had the heart of a mystic and an abiding love for St. Teresa of Ávila. His lifelong goal—which he was unable to achieve—was to translate all St. Teresa’s writings into Dutch.

Today, St. Titus, along with his fellow Carmelites St. Teresa of Ávila, St. John of the Cross, and St. Edith Stein, stand as symbols of hope—not only for me personally, but for the entire world. At a time when racism and antisemitism are alarmingly on the rise, I am guided by these four saints who teach me courage, strengthen my faith, and offer me comfort. They, as well as Our Lady of Mount Carmel, remind me that we have always been connected as one human family and that “we shall overcome.”

Our Lady of Mount Carmel

In the early 13th century, the first Carmelite hermits—who lived on Mt. Carmel, where the Prophet Elijah sheltered in a cave and erected an altar to honor the Hebrew God—named Mary Our Lady of Mount Carmel. Centuries later, the Carmelites built a monastery and chapel on the site dedicated to Stella Maris, the Star of the Sea. Eventually, the Carmelite order spread throughout Europe.

In my interpretation of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, Mary’s traditional brown scapular is embroidered with a Star of David while the child Jesus in her arms wears a yarmulke. Written on streamers in the trees behind her are the names of four Carmelite saints: Teresa of Ávila (1515–1582), John of the Cross (1542–1591), Edith Stein (1891–1942), and Titus Brandsma (1881–1942). I created the piece not only to illustrate this article but also to help me better understand the deep connections between Jewish and Carmelite spirituality across the generations, from Elijah’s time to our own.

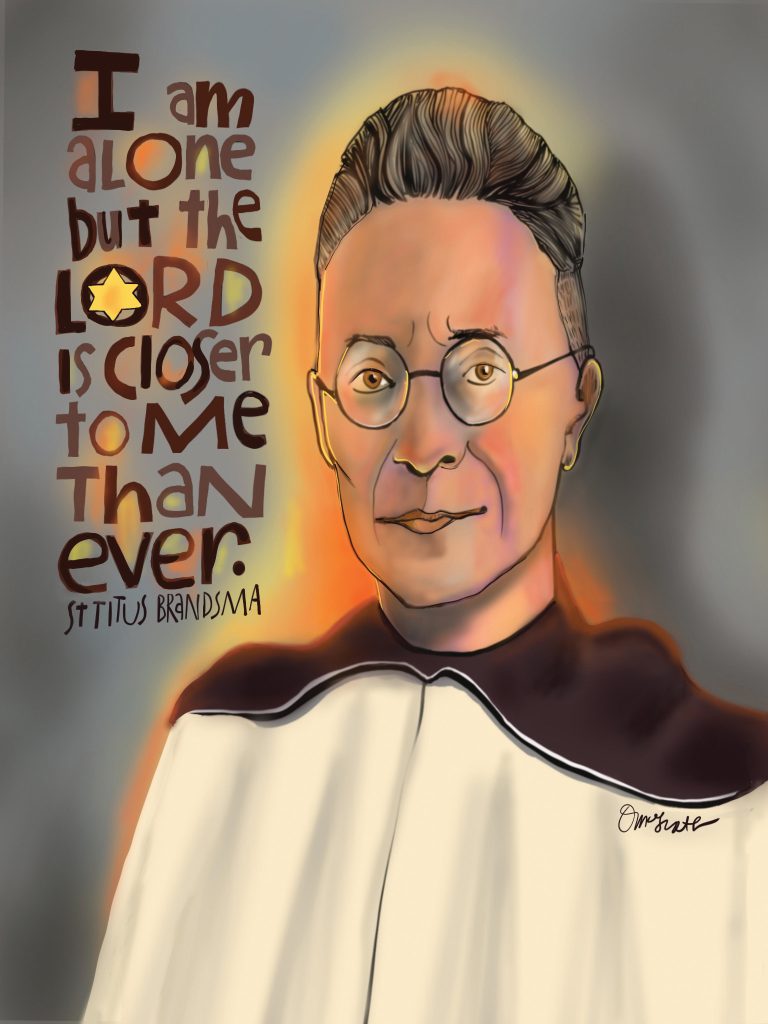

St. Titus Brandsma

St. Titus was a professor who bravely condemned Nazism in his Catholic university classroom. A forward-thinking, open-minded intellectual, he defended the rights of artists to express themselves, was active in ecumenical circles, openly criticized national socialism in his philosophy classes, and saw the main purpose of the Catholic press as spreading the gospel of love and mercy. In partnership with the Dutch bishops, he implored Catholic news editors to refuse the Nazis’ demands to publish antisemitic propaganda. Doing so cost him his life.

When the Nazis first jailed him, St. Titus wrote a poem on the face of Christ inspired by a picture on a holy card he managed to bring with him, thus creating a soulful connection to the 16th-century Carmelite St. John of the Cross, who also wrote poetry while imprisoned. St. Titus was nicknamed “Uncle Titus” by his fellow prisoners because of his kind and gentle nature. And it’s safe to assume he taught them his personal favorite of St. Teresa’s prayers: “Let nothing disturb you, let nothing frighten you. God alone is sufficient.”

St. Teresa of Ávila

St. Teresa of Ávila herself had Jewish roots in Toledo, a beautiful city renowned for the study of Jewish and Muslim literature and mysticism. Conversos was the term for Jews who converted to Catholicism rather than face exile from Spain or even execution due to antisemitic laws enacted during the reign of Ferdinand and Isabella—laws enacted with the support of popes and monitored by the Spanish Inquisition. By law, conversos were forbidden from holding church or government positions, teaching in Catholic universities, or entering religious orders unless they were third-generation Christians. Even then, they faced constant scrutiny and suspicion.

Both St. Teresa and St. John of the Cross—her fellow Carmelite doctor of the church—were of converso heritage and therefore should not have legally passed the test of limpieza de sangre (“purity of blood”). In 1485, the Inquisition accused St. Teresa’s converso grandfather, Juan Sanchez, a successful Toledo merchant, of secretly practicing his Jewish faith.

He was subjected to public humiliation and brutality along with his 5-year-old son, St. Teresa’s father. Soon after, Juan moved his family from Toledo to Ávila to make a fresh start.

Most scholars assume that St. Teresa knew of her Jewish background but didn’t publicly acknowledge it because of the repercussions. She had other challenges to overcome as a woman, writer, mystic, and reformer in a clerically dominant, status-obsessed church that didn’t look kindly on female mystics who preferred to nurture their own relationship with Jesus rather than rely on priests. St. Teresa bent the rules by continuing to write and by welcoming converso women into her reformed monasteries and accepting financial help from converso benefactors.

St. John of the Cross

St. Teresa’s work of reform influenced St. John of the Cross, who for a time served as spiritual director and confessor for her and many of her nuns. In courageously rising above the narrow restrictions of their time, Sts. Teresa and John reformed the Carmelites and the church at large.

Other leaders of the Carmelite order resisted their reforms, however. They captured St. John and locked him in a monastery, where he was subjected to isolation and public whipping. During this time of imprisonment, he composed some of his most celebrated mystical poetry. About eight months after his capture, St. John managed to escape his cell. Eventually, the pope allowed the Carmelite reformers to separate from the main order, and the “Discalced Carmelites” (named for their injunction against wearing covered shoes) became official.

St. Edith Stein

In 1940, nearly four centuries after Teresa’s death, the Germans invaded the Netherlands. Shortly afterward, inspired by St. Titus Brandsma, Dutch Catholic bishops issued a letter denouncing the Nazis and their persecution of the Jews. In retaliation, the Germans arrested hundreds of Catholics who were converts from Judaism and sent them to concentration camps. Among them was St. Edith Stein, a Carmelite nun who in her previous life was a philosopher and university professor in Germany. Raised in a Jewish family, St. Edith was an agnostic as a teenager. She studied under the phenomenologist philosopher Edmund Husserl and, after reading the work of Teresa of Ávila, later decided to convert to Catholicism and join the Carmelite order.

While they never met in person, Sts. Edith and Titus were both devoted to the work and spirituality of St. Teresa of Ávila. Yet neither of them could have known about St. Teresa’s Jewish heritage. They both died in concentration camps in 1942, she in Auschwitz and he in Dachau.

I am deeply grateful that “Uncle St. Titus” entered my life and inspired me with a new awareness of God’s silent, pervasive presence in our troubling era. Through his intercession, that of his fellow sainted Carmelites—Teresa, John, and Edith—and that of Our Lady of Mount Carmel may we be led by the gospel of love, each in our own way, to eradicate antisemitism and racism from the world once and for all.

This article also appears in the October 2023 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 88, No. 10, pages 10-13). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

All Images: Brother Mickey McGrath, O.S.F.S.

Add comment