I love Holy Week. With its processions, readings, incense, colors, and music, it is the most theatrical time of the liturgical year, when each of us can step into the rich tradition and oral history of our faith.

As a working actor, I know that “theatricality” doesn’t have to mean falseness or ostentation; it can be a vibrant, communal, embodied form of telling the story of our salvation. We find sacred theatricality in the extravagant passion plays that draw crowds every year from Australia to Brazil; in the humble Christmas pageants held in church basements; in the procession of palms on Passion Sunday, the stations of the cross, and the reenactment of the first eucharistic meal at every Mass.

Since the founding of the church, Catholics have been physically acting out the drama of our faith. We recite prayers and break into song. We role-play as acolytes, lectors, and musicians, saying words and going through motions that generations have performed before us. Theater has always been central to the way Catholics worship, contemplate, and understand God.

My Catholic background has greatly influenced my approach to theatrical performance. Knowing the power of a story that feels both personal and universal, I decided to apply acting techniques to reading scripture, a kind of lectio divina for actors. Through this I found a beautiful new way of “putting on Christ” and feeling immersed in the stories from scripture.

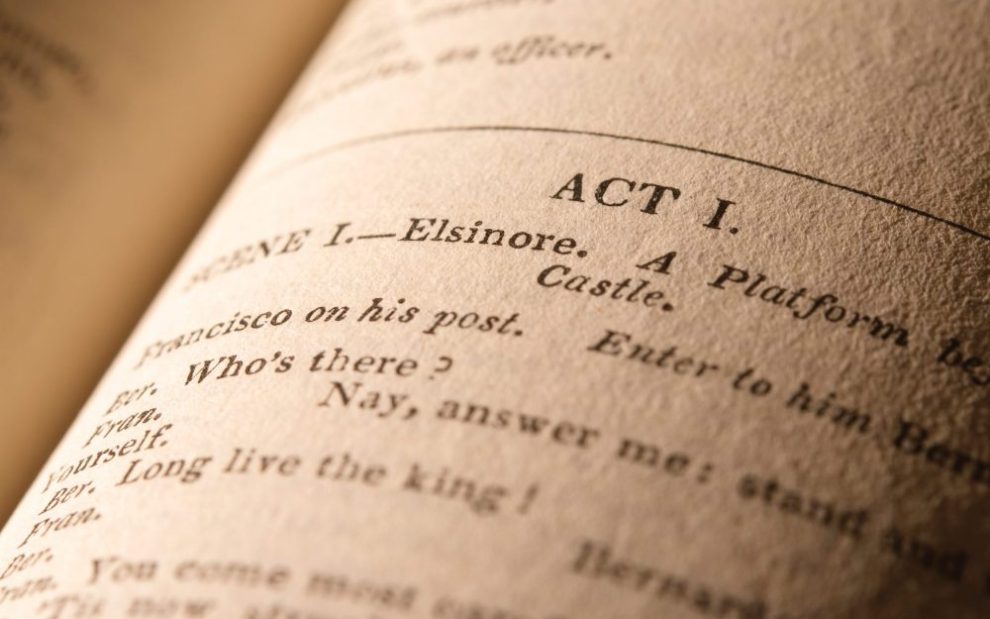

And where better to start my experiment than with William Shakespeare, who was possibly a closeted Catholic himself?

Like scripture, Shakespeare’s plays were written to be shared aloud. And like the people in scripture, Shakespeare’s characters—from Juliet to Othello, Lady Macbeth to Hamlet—bridge legend and reality as they confront ultimate questions of faith and doubt, exile and homecoming, power and honor, good and evil. An actor’s approach to Shakespeare requires careful attention from the mind and full engagement of the body. What would happen if I engaged my mind and body in reading scripture the way I did while working on a Shakespearean monologue?

I chose five tools from my Shakespearean acting toolbox and a favorite reading from the triduum. The first, simple as it may seem, is the reminder that every word matters. When confronting a new Shakespearean monologue, an actor must accept that each word—whether flowery poetry or bald-faced prose—is chosen by the character (not the author!) for a reason. Finding the reason is what gives the moment life.

For my experiment, I chose the Farewell Discourse from the Gospel of John (John 14–17). It is one of the closest things to a monologue I could find in the gospels. Viewing this gospel scene like a Shakespearean scene means meditating on why these characters say what they say. Since this is a spiritual exercise, not a scholarly one, reading scripture in translation didn’t keep me from feeling empowered to give each word its due importance.

After committing to take no word for granted, I focused on understanding the given circumstances, or the context in which a scene happens. I asked myself: Who is there? Who is talking? Who is listening? What made these events happen? I pushed myself to go beyond baseline assumptions and imagined the scene as if it were my first time.

The given circumstances of the Farewell Discourse are that a dying man is sharing a meal with his closest friends and has important things to tell them. He chooses simple words. He reassures. He challenges. He uses wit. The character of Jesus is not issuing instructions or peering into the future like a seer but looking into each beloved, sometimes hapless face and saying things over and over so they’re understood. Taking the time to imagine this moment made the passage more urgent, surprising, and moving. I found myself leaning in to catch every word.

The next tool was simple but deceptively effective: Whenever I saw a question mark, I actually asked the question. It’s common advice to avoid viewing any of Shakespeare’s questions as rhetorical, even if the speaker is alone.

When I really asked the questions that Jesus asks his disciples during the Farewell Discourse, it felt less like a monologue and more like, well, a discourse. The scene shifted from Jesus standing stoically in front of silent followers to Jesus looking into their eyes, inviting interaction. The scene became more complete, the characters more real, and the esteem—even respect—Jesus had for his friends more pronounced. He wasn’t just announcing, “I have called you friends”; he was demonstrating it. A God who leads by example rather than command, who acts out a mission while verbalizing it.

Next, I focused on repetition. Actors know that Shakespeare’s repetition is always intentional. It emphasizes the point and builds intensity. Shakespeare didn’t make an anguished Lear say, “Never, never, never, never, never” for no reason. Each “never” is more vital than the last.

Jesus repeats himself a lot in the Farewell Discourse. As I read aloud, I tried to experience the repetition as intentional. Words popped out at me: “Love” and “joy” shone like beacons throughout—not what I expected, given what was about to happen. Whole phrases were repeated: “Ask for whatever you wish, it will be done for you”; “I will come again”; “When the Spirit of truth comes, he will guide you into all the truth.” The repetition characterizes Jesus as comforter, nurturer, and mothering friend—an unexpected note in the drama of Holy Week, in which Jesus is often a tragic figure, defiant king, martyr, victim, or sacrifice.

Finally, I emphasized the verbs. In his book Thinking Shakespeare (Theatre Communications Group), renowned stage director Barry Edelstein calls verbs “the hardest-working words in show biz,” the “life force” of language. “Find them, embrace them, and let them rip,” he instructs. An actor must never breeze through a Shakespearean verb without giving it the weight it deserves.

In emphasizing the verbs, I was struck by how active the text became. Jesus repeats his central verbs frequently: love, hate, give, reveal, go, and come. His final words are not about ideology. They are instructions—in acting terms, with “playable notes.” He’s telling us how to act. Jesus envisions the world as an active, vibrant place.

Using Shakespeare to explore the Farewell Discourse allowed a tender, intimate look inside a tightly bonded circle of friendship on the brink of disruption. Jesus wasn’t the detached teacher I’d remembered from previous readings; he was the attentive mother hen from Luke 13:34, honest yet optimistic, who intuits what others need to hear. He was speaking to real, three-dimensional people he loved. He wasn’t aloof from his feelings; he was in the thick of them as he comforted and prayed.

But along with rediscovering Jesus’ humanity, putting on Christ also reminded me of Christ’s divinity within me, promised in this very discourse: “On that day you will know that I am in my Father, and you in me, and I in you” (John 14:20).

Theatrical storytelling, whether on stage or at the altar, has the potential to be sacred for both the listener and the teller. This belief keeps me going back to work, to rehearsal, to auditions, even though it’s a difficult and unpredictable life. Surely it’s the belief that kept Shakespeare writing through plagues, political violence, even the death of his beloved son. And this belief is renewed when I see people gather to hear the word, to sing the psalms, to process with palms, to participate in our theatrical faith. As you encounter the scriptures this Holy Week, consider letting your inner actor guide you toward a new encounter with the Word made flesh.

This article also appears in the March 2023 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 88, No. 3, pages 45-46). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: iStock.com/221A

Add comment