Many people struggle to understand the relationship between justice and charity. Are they opposites? Complementary? Is any form of care for the poor automatically charity? Should all such care be the sole obligation of the individual? How does the state fit in to all this?

It’s a real question we face often. For instance, the Biden administration recently proposed no longer cutting SSI monthly benefits for people who get additional help with meals or groceries from friends and family. Some complain that this is unfair, but the biblical tradition urges us to remember what the church calls the “preferential option for the poor.” The paradox of that option is expressed in Deuteronomy 10:17–19, which states that God is “not partial,” but that this divine impartiality manifests itself through justice and the righting of wrongs: God “executes justice for the fatherless and the widow, and loves the sojourner, giving him food and clothing.”

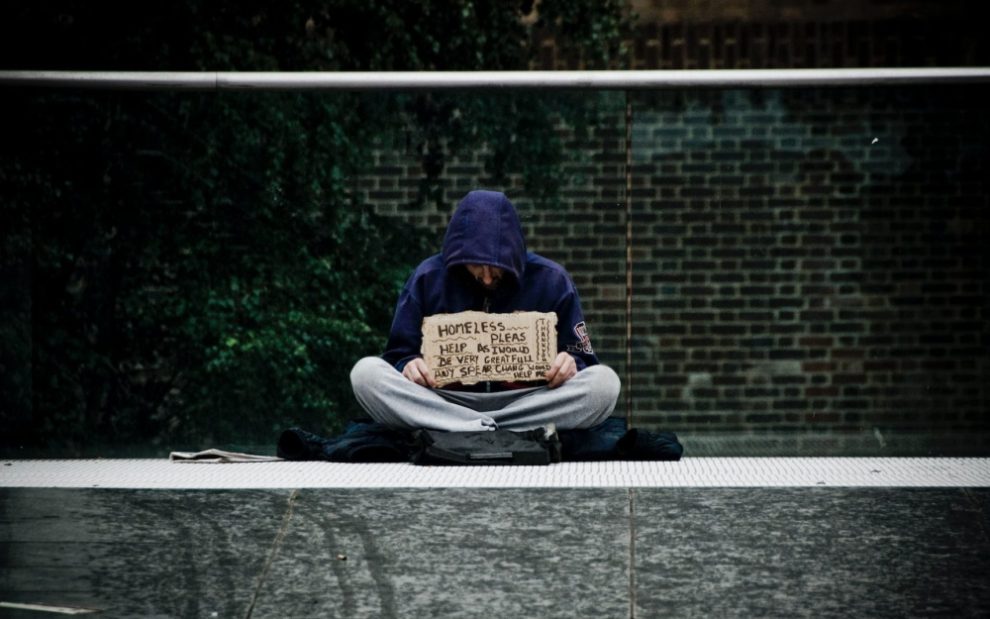

This is God from the perspective of the weakest, the outcast, the lowest, the poorest, and the most wretched. God takes their part because, while the rich may have battalions of lawyers, stockpiles of guns, and plenty of money, the weak and the poor have no one to defend them. We are called to imitate this divine impartiality, as Jesus did, when he took his place with the least of these and literally had no place to lay his head (Matt. 8:20). When Jesus was on trial for his life, he too had nobody to defend him. And he taught us that we do for (or to) the poor, we do for (or to) him.

It is commonly believed that all help given to the poor counts as charity. So, the argument goes, it is good for Christians to be personally generous to the poor. But what, many ask, is the sense of involving the state? If the state helps the poor, doesn’t that interfere with the individual doing so?

The trouble with this approach is that it takes the focus away from the poor or the outcast getting what they need and fixates instead on who gets the credit for helping them.

Here’s the biblical truth: According to the church, much of what we do for the poor and the outcast is owed to them. It is justice, not charity. Failure to admit this is the sin that the rich man in Jesus’ parable committed when he neglected the beggar, Lazarus, at his gate. In the story, the rich man ignores Lazarus, enjoying his life of luxury, but then dies and finds himself in hell. But the rich man was not being punished for his failure to be charitable. His failure was one of justice. He refused to give Lazarus what he owedhim. For the same reason, the Samaritan in Jesus’ most famous parable did not show charityto the beaten man lying by the road. Rather, he gave him what he owed him as his neighbor.

Charity is not owed. Charity is pure gift. If I am sitting next to you on the bus and don’t hand you $10, I am not sinning against you: I do not owe you $10. You have no claim in justiceon my $10. If I give you $10 anyway, that is charity: an act of loving generosity I need not have done but do anyway, out of kindness or love.

But if I step off the bus and find you lying injured on the sidewalk and I do nothing, I deprive you of justice—not charity. Why? Because as a human being made in the image and likeness of God, you are owed your life, and the care of your community.

St. Gregory the Great summed it up this way: “When we attend to the needs of those in want, we give them what is theirs, not ours. More than performing works of mercy, we are paying a debt of justice.”

That is why the state as well as the individual is involved in the care of the poor. The reality is that the needs of the least of us are often not met for a host of reasons. And this is unjust. It is not the job of the state to do charity, but it is absolutely the task of the state to ensure justice: to see that the most vulnerable among us do not starve, that families have drinkable water and shelter, that young people receive an education, that adults have access to meaningful work, that our communities have functional roads, that everyone gets adequate medical care. All human beings are owed those things in justice because of our fundamental human rights. That is not socialist utopianism. That is bedrock Catholic doctrine about the dignity of the human person and the demands of the common good.

“The responsibility for attaining the common good, besides falling to individual persons, belongs also to the State, since the common good is the reason that the political authority exists…. The individual person, the family or intermediate groups are not able to achieve their full development by themselves for living a truly human life. Hence the necessity of political institutions, the purpose of which is to make available to persons the necessary material, cultural, moral and spiritual goods” (Compendium 168).

There are two crucial things to note here. The first is that the church puts the needy, not their benefactor, at the center of the common good. As of this writing, about one-third of all GoFundMe campaigns are devoted to helping people pay for their enormous medical costs. When parents of a girl with leukemia are facing astronomical medical bills, the issue is about caring for the child and saving her family from living under a freeway overpass, not about the sanctification of their benefactor or the well-off person’s feeling of having done an act of kindness. If the state can provide health care for them without their economic destruction, then let it be provided. If some private benefactor can do it, then let them provide it. But the point, again, is providing for the health care needs of the sick, not who gets the credit.

And that leads to our second point: Because the church puts the needs of the needy, not the methods we use to meet these needs, at the center of the equation, we shouldn’t waste too much time worrying about whether individual generosity or a state social safety net is the exclusive ideal. This is like worrying about which blade on the scissors does the cutting. Developed nations with robust safety nets and a state health care system do not thereby render their citizens incapable of all personal charity. Developed societies can provide basic human necessities such as food and shelter both by private and public means. The point is to care for those who are most in need.

Our duty as Catholic citizens involves a both/and, not an either/or approach to the question of justice and charity. We pay the taxes we owe so that the common good can be served by the state but also remain alert to opportunities to share the gifts we have received from God, both material and spiritual, with our fellow humans.

Image: Unsplash/Jean-Luc Benazet

Add comment