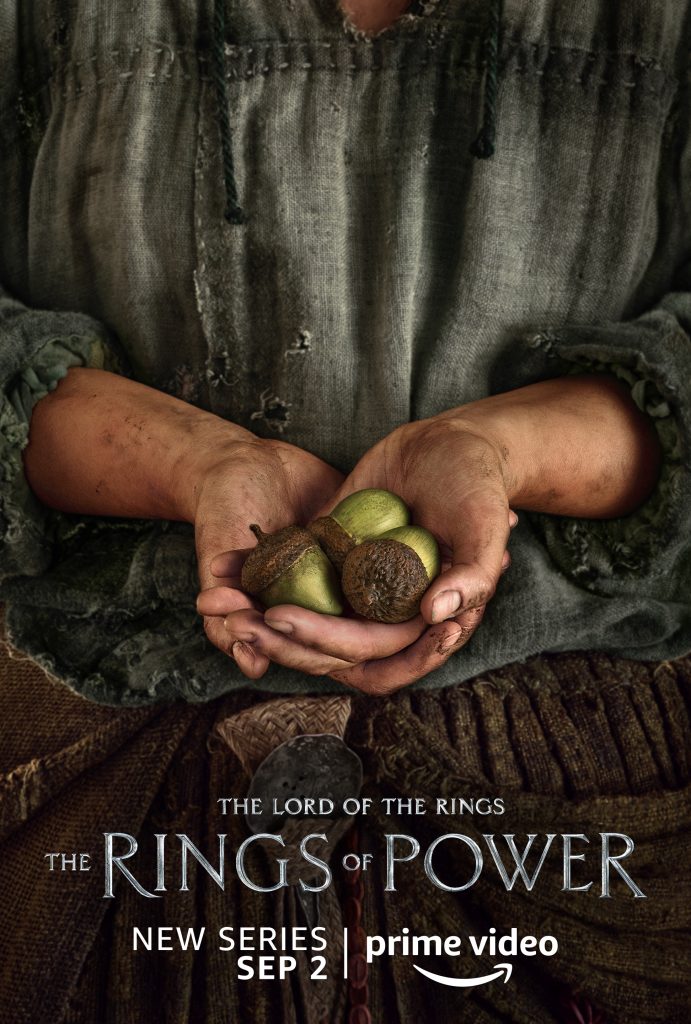

The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power

Developed by J.D. Payne and Patrick McKay (Amazon Studios, 2022)

Catholic tradition has always held evil to be a privation of what in origin is fundamentally good. The Book of Genesis tells us that God looked out on the world when God finished forming it and declared it good. Evil as a force of its own forms no part of creation.

This is a key theme underlying Amazon’s much anticipated Lord the Rings: The Rings of Power. It’s interesting to consider how the series’ producers fleshed out the origins of evil in J. R. R. Tolkien’s Middle Earth, staying true to Tolkien’s own Catholic sensibility. “Nothing is evil in the beginning,” as one of the chief characters states in The Fellowship of the Ring.

Of equal importance to Tolkien in his fantasy world is a fundamental diversity of races. As a Catholic in early 20th-century Britain, Tolkien grew up aware of the prejudice against his faith and church throughout his life. He was careful to reveal and dramatize this awareness through the tensions between the elves, dwarves, men, and hobbits that populate Middle Earth.

It’s all the more ironic, then, that even before the first episode of Amazon’s series premiered, controversy arose about what Tolkien purists complained was the producers’ forced inclusion of people of color in major roles to make Middle Earth appeal to members of a wider audience, many of whom were not even born when Peter Jackson’s spectacular film adaptations were released 20 years ago.

But series producers J. D. Payne and Patrick McKay have succeeded in assembling a marvelous troop of believable actors, staying true to the diversity at the heart of Tolkien’s work from the earliest of his writings. For example, by starting with the darker-skinned hobbits (the Harfoots), the series sets up the future meeting of these rustic travelers with their more adventurous and fairer-skinned Fallohide and Stoor relatives. Indeed, Tolkien deliberately modeled the three ethnic groups of hobbits on the three major ethnic groups that established England in the early Middle Ages: the Angles, the Saxons, and the Jutes.

Then there is the wider inclusion of women in major roles, compared to the Lord of the Rings books themselves, but in keeping with Tolkien’s older, darker work, The Silmarillion. The main driver of the series is “young” elven Galadriel, centuries before she will become the Lady of Lothlórien and the friend of Frodo Baggins. In The Rings of Power, she is the central character, bringing together the plotlines of the other peoples in their struggle to rescue Middle Earth from the encroaching menace of orcs, massing anew since the downfall of the first Dark Lord.

Building the main structure of the season around Galadriel and her quest to root out the chief servant of the vanquished Dark Lord wherever she can find him is also a solid anchor for the eight episodes. Morfydd Clark is commanding in the role (indeed it’s a little jarring to hear her addressed as “commander” by her soldiers), in spite of the often wooden dialogue she has to work with and some of the overly contrived obstacles that often stagger the series’ momentum, discussed below.

Given that the entire series is a prequel to the original cycle of Jackson’s films, I think the producers also succeeded in finding actors that looked enough like their later “selves” to be intriguing, subtly suggesting how experience and wisdom can over time physically alter even immortal beings like the elves that are not “doomed to die.”

In terms of the momentum through eight episodes, the series only seems to stall where it is overly committed to some of the outright departures from Tolkien’s timeline. The departures are by no means showstoppers, given the superb performances of the entire cast. Joseph Mawle as Adar, an emerging Dark Lord, is haunting. In addition to presenting a beautifully underplayed menace, his character presents a much-needed fleshing out of how the orcs came into being (only suggested in Jackson’s films) and even a sense of grievance against their former masters. This, again, is in keeping with Tolkien’s own attachment to Catholic tradition: “Nothing is evil in the beginning.”

But here, one can have reservations about how the producers chose to go off-trail from Tolkien and in the process lost an opportunity to more deeply explore the connection between the elves and their craft—a connection that is almost sacramental in nature and that was always fundamental to Tolkien’s work.

Grace is never an abstract idea for Tolkien. Rather, it is something real that can be passed from creator to creature—and from creature to creature. The liturgy describes both bread and wine as the “work of human hands,” even though we understand from tradition that our human hands are sinful. Nevertheless, they establish the means through which the Eucharist is granted to us.

For Tolkien, the immortal elves are to be understood in a crucial way, as humans that never suffered the metaphysical and physical consequences of original sin. In this regard, in addition to being immortal, everything the elves make, and everything they establish, has an overflowing grace that can bring supernatural and natural benefits to whomever they contact.

The Rings of Power has (thus far) not explored this crucial aspect of Tolkien. But perhaps it will in the next season.

Image: Ben Rothstein/Prime Video

Add comment