When I taught New Testament to high school juniors, I always looked forward to the unit on the infancy narratives of Jesus. One of my favorite assignments involved asking students to identify the scriptural roots of various Christmas hymns and songs. We would listen to classics such as “O Holy Night” and “The First Noel,” as well as more contemporary hits such as the ’90s cult anthem “All I Want for Christmas Is You.”

While Matthew and Luke are the only two evangelists who provide accounts of the events surrounding Jesus’ birth, their descriptions give us the familiar images we have come to know and associate with the Christmas season. Matthew tells of the star, the magi, and a king whose lust for power could not be sated without the murder of a child. Likewise, Luke tells of the circumstances surrounding Mary and Joseph’s journey to Bethlehem and the heavenly angels who announce the good news to a motley group of shepherds.

But Luke’s gospel has something else that is not present in Matthew: Luke includes four canticles or songs in his infancy narrative, all of which appear during the scripture readings of the Advent and Christmas seasons.

Mary proclaims a great hymn of trust in God as she embraces her cousin Elizabeth, singing, “My soul magnifies the Lord, and my spirit rejoices in God my savior, for he has looked with favor on the lowly state of his servant. Surely from now on all generations will call me blessed” (Luke 1:46–48).

Similarly, after the birth and naming of his son, Zechariah prophesizes God’s saving work, saying, “Blessed be the Lord God of Israel, for he has looked favorably on his people and redeemed them. He has raised up a mighty savior for us in the house of his child David” (Luke 1:68–69).

At the birth of Jesus, the angels praise God, singing, “Glory to God in the highest heaven, and on earth peace among those whom he favors!” (Luke 2:14).

Finally, when Jesus is presented in the Temple, Simeon exclaims, “Master, now you are dismissing your servant in peace, according to your word, for my eyes have seen your salvation, which you have prepared in the presence of all peoples” (Luke 2:29–31).

While there is debate about the origins of these canticles, most scholars agree that they were probably Jewish hymns. In A Coming Christ in Advent (Liturgical Press), Raymond E. Brown writes, “Although in the Infancy Narrative Luke has various characters speak these canticles, modern scholarship has moved away from thinking that they were respectively the historical compositions of Mary, Zechariah, or Simeon (or a fortiori, of angels). They have an overall common style and a poetic polish that militate against such individual, on-the-spot composition. . . . If these were the hymns of early Jewish Christians, they now appear in the Gospel on the lips of the first Jewish believers.”

The circumstances of these songs are indeed joyful. Mary shares the joy of her consent to God’s work within her. Zechariah praises the God of covenantal love. The angels rejoice at the birth of a savior. Simeon celebrates that he has seen the God who saves.

It may seem surprising, then, that the text of these songs is not so easily digestible. Each canticle names harsh realities and issues bold claims. Mary sings of the God who throws down the mighty rulers from their thrones and lifts up the humble, who fills the hungry with good things and sends the rich away empty. Zechariah prophesizes that through God’s tender mercy the dawn will break on those who sit in darkness and the shadow of death. The angels sing of the glory of God to a group of shepherds, allowing lowly vagabonds to be the first to know the good news of Christ’s birth. Simeon proclaims of the salvation brought to a people who have known exile and disparagement.

Each canticle speaks to upsetting the status quo, protecting the vulnerable, and bringing life to people who live in fear. These first Christmas songs are joyful, yet they do not ignore the significant realities of sadness and suffering, longing and woundedness. This is the mystery of the incarnation. God chooses to share Godself with all of creation, participating in human life in a way that goes beyond watching from a distance. Through the incarnation, Christ is intimately present with and in all people, including those who know hurt and rejection.

Pope Francis often reminds us of this reality. In his Christmas message last year, he spoke of the dialogical nature of the incarnation: “The Word became flesh in order to dialogue with us. God does not desire to carry on a monologue, but a dialogue. . . . By the coming of Jesus, the Person of the Word made flesh, into our world, God showed us the way of encounter and dialogue.”

We see images of this dialogue in some of our favorite Christmas songs. “Once in Royal David’s City” sings of the God who “was little, weak, and helpless.” “O Little Town of Bethlehem” tells us “where meek souls will receive him, still the dear Christ enters in.” It is only through the ordinary littleness that God’s saving action is possible. “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing” reminds us that a child is “born that we no more may die.” The traditional African American spiritual “Go Tell It on the Mountain” proclaims, “Down in a lowly manger the humble Christ was born, and God sent us salvation that blessed Christmas morn.”

Consider also Adam M. L. Tice’s stunning contemporary hymn “A Weary Couple,” sung to the tune of “Londonderry Air (Danny Boy).”

A weary couple lodged within a stable,

the only space where they could spend the night.

Were other trav’lers happy to be able

to keep her labor out of mind and sight?

But choirs of angels heard the mother’s weeping,

and heaven rang with songs of peace on earth.

They went unheard by those in comfort sleeping,

for Jesus came among the outcasts at his birth.

An angel came to Joseph in his dreaming

and warned him so his family could flee.

As they escaped King Herod’s evil scheming,

the Son of God became a refugee.

How many children die without such warning?

How many mothers will not be consoled,

their voices choked with anger, tears, and mourning,

for songs unsung and stories never to be told?©

This text vividly portrays the reality of Christ’s birth in a holy and provocative way. The questions posed are not light, nor are the answers easy. There is pain and suffering in our world that need to be named and addressed. Ableism, homophobia, racism, sexism, and xenophobia run rampant in our hearts, homes, communities, and churches. They are often exacerbated during the holiday season. Corporate parties are not accommodating of all people. Adult children fear returning to their homes. Sickness disproportionately affects people of color. Misogynistic jokes at the table make for uncomfortable dinners. And people who do not celebrate Christmas are vilified, both unintentionally and intentionally.

But this darkness does not have the final word. Because of the incarnation—because God becomes human—we can find hope this Christmas season. The concluding verse of Tice’s text reminds us of this:

But still the angels sing their hymn of “Glory”

beyond our fears that never seem to cease.

For Christ has come, and God’s unfolding story

redeems the world to live in love, good will, and peace.©

Should Christmas music be less joyful? No. But like the first Christmas songs in Luke’s gospel, it can’t ignore the messy realities of

the incarnation.

Words and Arrangement © 2018 GIA Publications, Inc. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

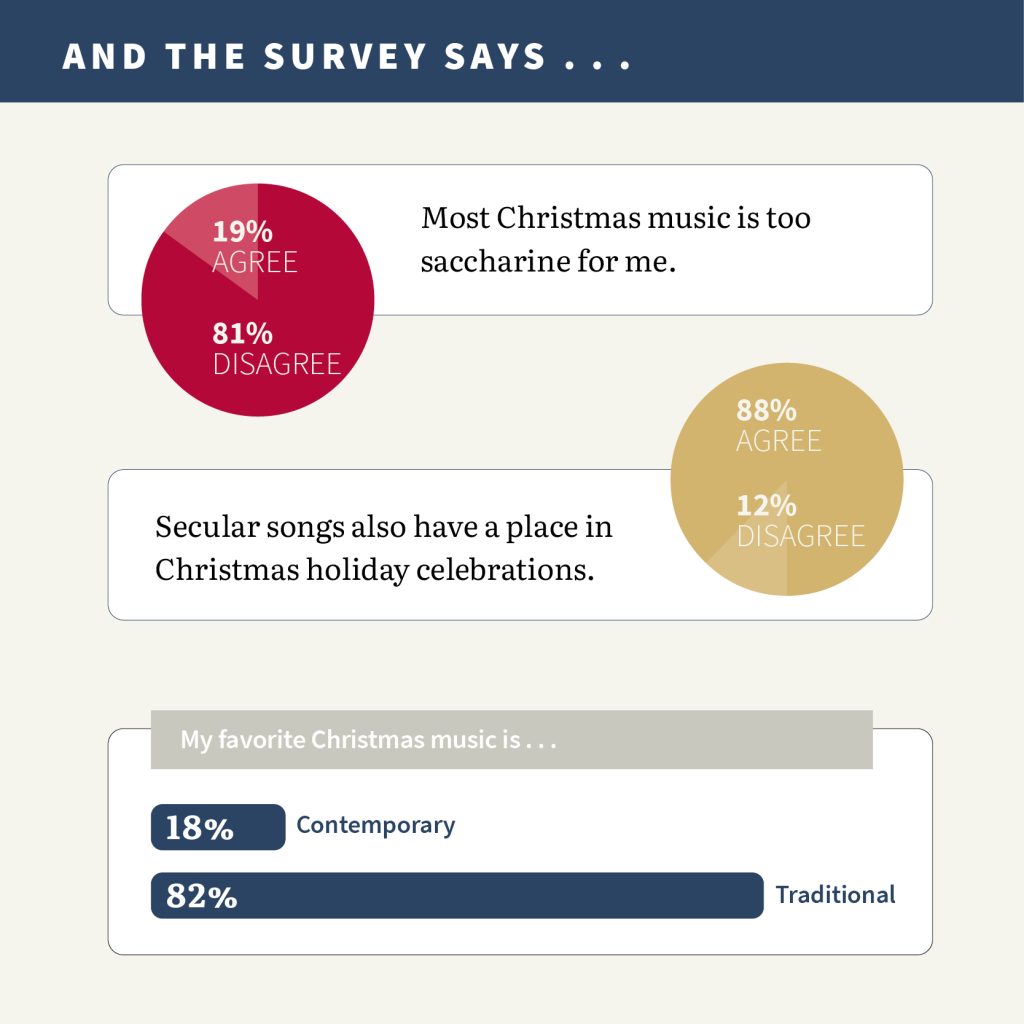

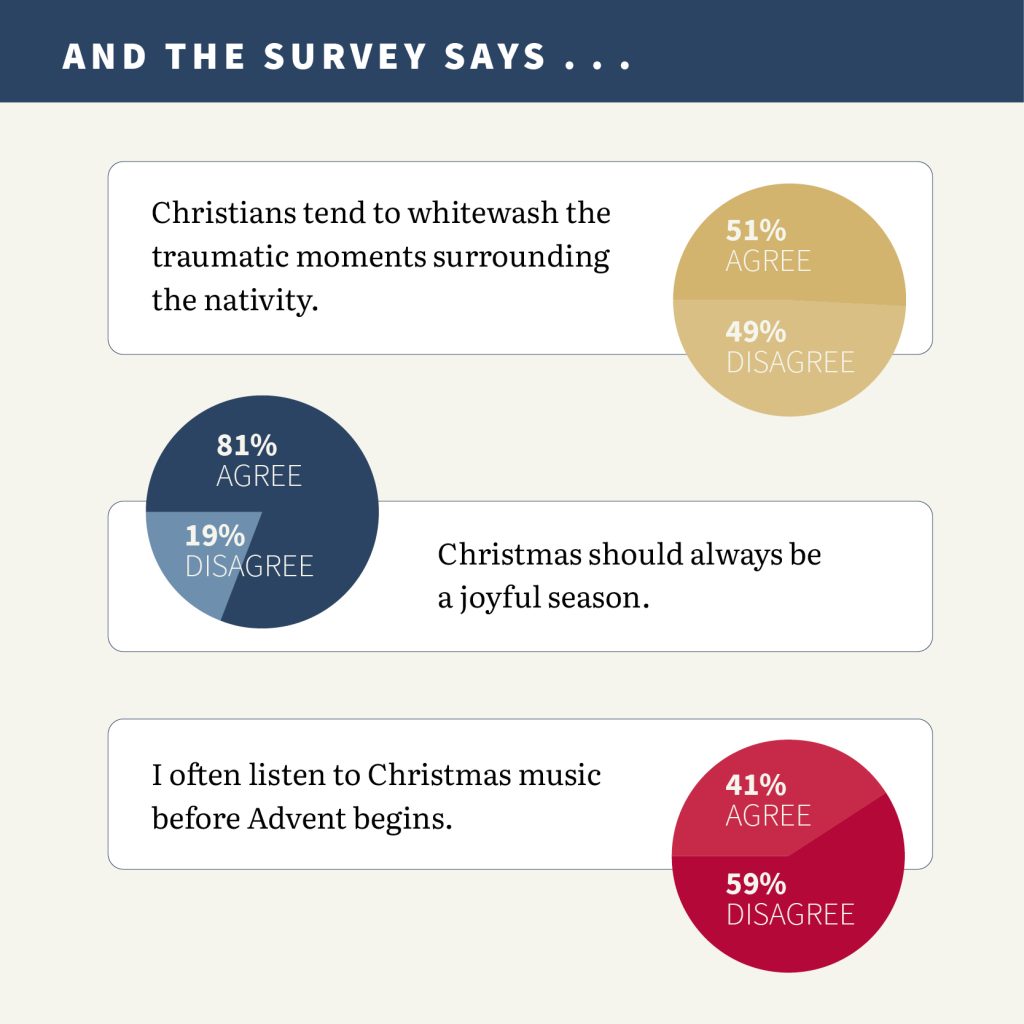

Survey results are based on responses from 98 USCatholic.org visitors.

Sounding Board is one person’s take on a many-sided subject and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of U.S. Catholic, its editors, or the Claretians.

This article also appears in the December 2022 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 87, No. 12, pages 31-35). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Unsplash/Annie Spratt

Add comment