Madonnas of Color (Clear Faith Publishing) takes you on a rich journey of theological aesthetics. Brother Mickey McGrath weaves together personal reflections, various spiritual writings, and commentary on the value of art to further conversations on dismantling systems of oppression. McGrath proudly opens the book with what he deems the biggest honor of his career, which came by way of an African American parishioner on a spiritual retreat in Saginaw, Michigan. While examining his art, an older Black woman, amazed at the various portraits of Black and Brown images of Mary and Jesus, remarked, “Well honey, you have a Black soul.” McGrath took this grace-filled moment as confirmation from the Spirit to continue his acts of artistic resistance by way of painting Madonnas of color.

Orphaned in his 30s after the death of his father, McGrath began to struggle with finding meaning in his vocation as a religious brother and artist. But the love and faith of another Black woman pulled him out of his grief and into a new era of artistic inspiration. Moved by the life of Sister Thea Bowman, McGrath acknowledges that her witness taught him that “music, art, and beauty of any kind are the best connectors we have as a diverse human family in search of love and in desperate need of unity.” For him, the most captivating beauty comes from the margins—a sentiment that he assures readers has been true in every time and place throughout history.

Some of the most spiritually enriching sections of the book include those where McGrath reflects upon the movements of Spirit Sophia, who inspires his observation that God is always present in what he calls “Gabriel announcements/annunciations.” He defines these as those “out of the blue” moments where something that appears ordinary catches our attention and provokes us to a silent awareness of God’s goodness, our response being one of gratitude. Drawing further on the image of the annunciation, McGrath notes that the darkness of the Black Madonnas reminds us that beneath the rich, black, fertile soil new seeds of life grow upward. These tiny particles of heaven emerge from the womb of Mother Earth.

It is clear that the spirit of Mary through the embodiment of McGrath’s Madonnas of color continues to give birth to spiritualities of survival and resistance. Highlighting several devotions throughout Africa, the Caribbean, East Asia, Latin America, and the United States, McGrath showcases the stories of Madonnas who have appeared to those most oppressed and marginalized in our world, instilling in them a sense of hope and salvation from suffering.

Vietnam’s Our Lady of La Vang was a Marian apparition who appeared to persecuted Vietnamese Christians in 1798. Routinely hiding in the surrounding jungles, villagers often prayed the rosary until one day a vision of Mary holding the infant Jesus appeared to them in the trees. The story goes that, due to a contaminated water source, sickness was spreading rapidly throughout the village. Knowing this, our Lady instructed the people to make tea by boiling leaves from the tree in which she appeared. This miraculously cured the villagers.

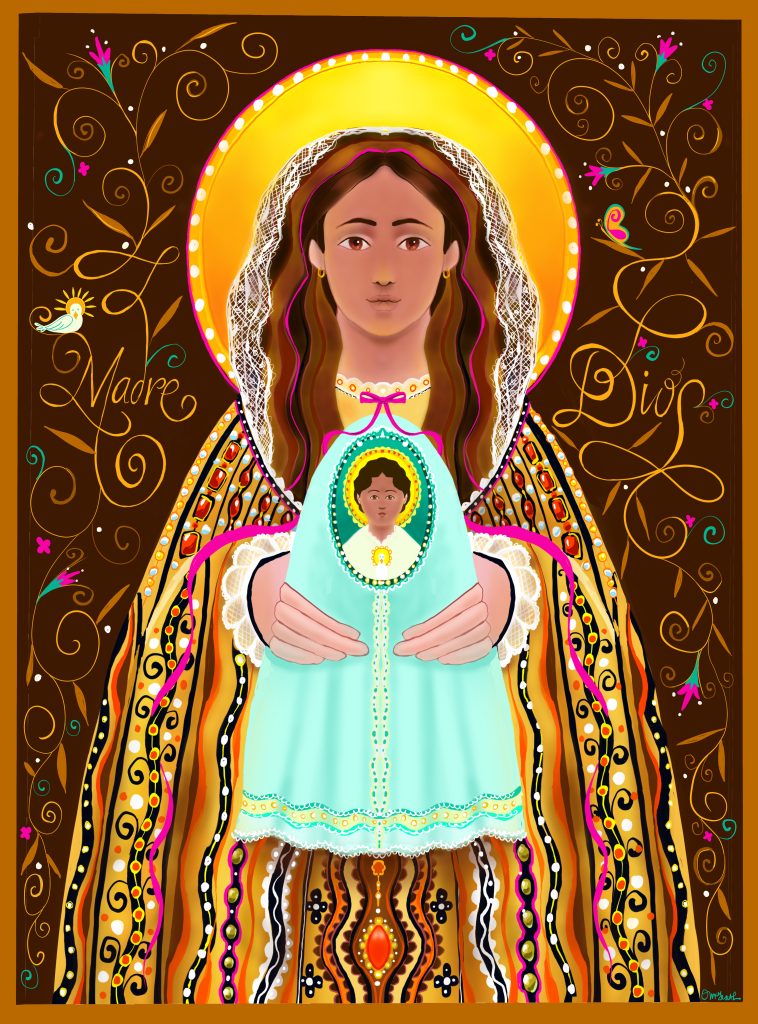

Mexico’s well-known Our Lady of Guadalupe appeared to the indigenous Juan Diego on the small hillside of Mount Tepeyac just outside of Mexico City in 1531. The miraculous account of her apparition—as recorded in the Nican Mopohua—finds Juan Diego traveling throughout the Mexican countryside until he begins to hear beautiful music and what he thinks is someone calling his name. After encountering a brown-skinned woman who identifies herself as the “Ever-Virgin Holy Mary, Mother of the God of Great Truth, Teotl, of the One Through Whom We Live, the Creator of Persons, the Owner of What Is Near and Together, the Lord of Heaven and Earth,” Juan Diego is instructed to travel to the archbishop of Mexico and inform him that a shrine should be erected in her honor at Tepeyac. Following several failed attempts to convince the archbishop of her appearance, Juan Diego is instructed to gather nonnative flowers from the top of Tepeyac where they are arranged by the Virgin in his tilma. Upon his return, Juan Diego opens his tilma before the archbishop who finds Castilian flowers falling at his feet and an image of the Virgin on the fabric.

Other narratives from Brazil and the United States also offer miraculous accounts of devotion to Mary, specifically her solidarity with enslaved Africans in the diaspora. Brazil’s Our Lady of Aparecida was a Marian statue found in the water by three fisherman who later erected a shrine to her. Enslaved persons traveled from all over to seek her intercession from their Portuguese oppressors. In fact, many Afro-Brazilians are still especially devoted to her today, her Blackness being interpreted as God’s condemnation of slavery. Finally, Our Lady of Stono is the incredible true story of enslaved Kongolese Catholics in South Carolina. Prior to their arrival in the “New World,” Mary was revered as Mamanzambi, or Mother of God, in Catholic Kongo, where a fervent devotion to her existed. Upon their arrival in the Carolinas, these enslaved Black Catholics erected a small shrine to her in the woods on a farm near the Stono River. On September 9, 1739, a band of freedom fighters—in part fueled by the energy of Mary’s feast day on September 8—led an armed insurrection against their enslavers, chanting Lukanga, the Kongolese word for “liberty” and “freedom.”

McGrath rightly states that it can be easy for many white Christians and contemporary followers of Christ like him to look back upon the horrors of colonization and slavery—traumas which inevitably permeate our interconnected histories—and opt for a posture of shame or guilt. However, he is adamant that white Christians can neither ignore nor excuse their acts of complicity or complacency toward history’s victims and survivors. Rather, his task as an artist is to respond in a spirit of truth, peace, and reconciliation to these accounts by first acknowledging the gut-wrenching pain of BIPOC persons. For him, genuine acts of penance look like the intentional creation of dark-skinned icons, since icons are continually whitewashed by the biases and racist attitudes of the church.

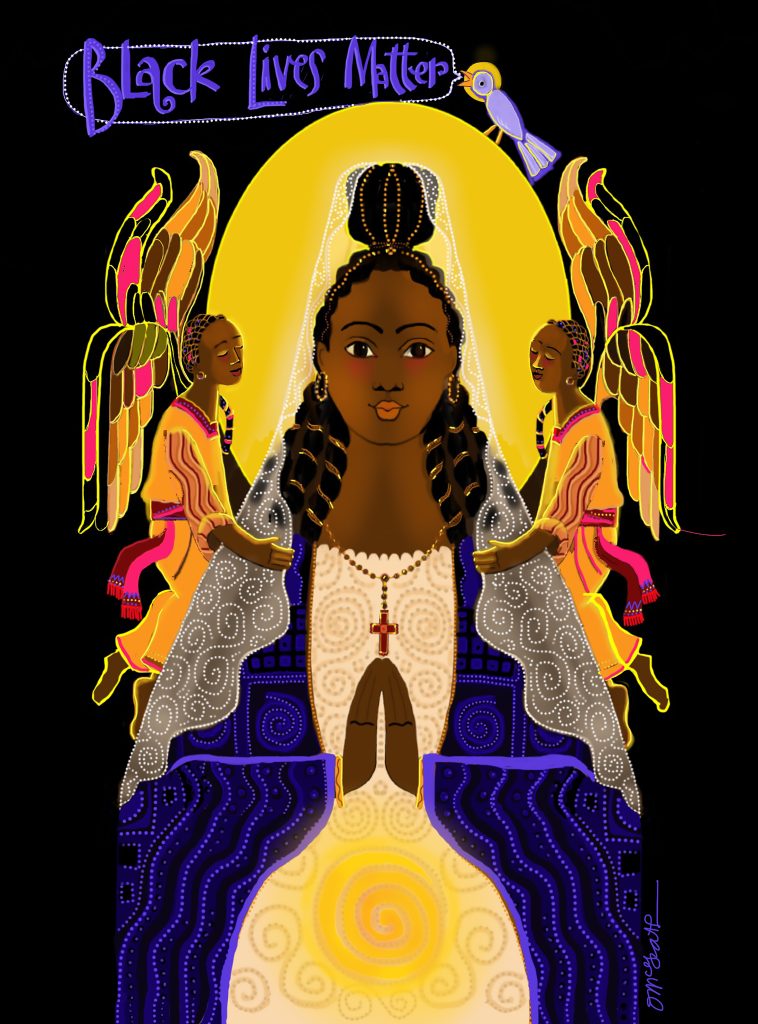

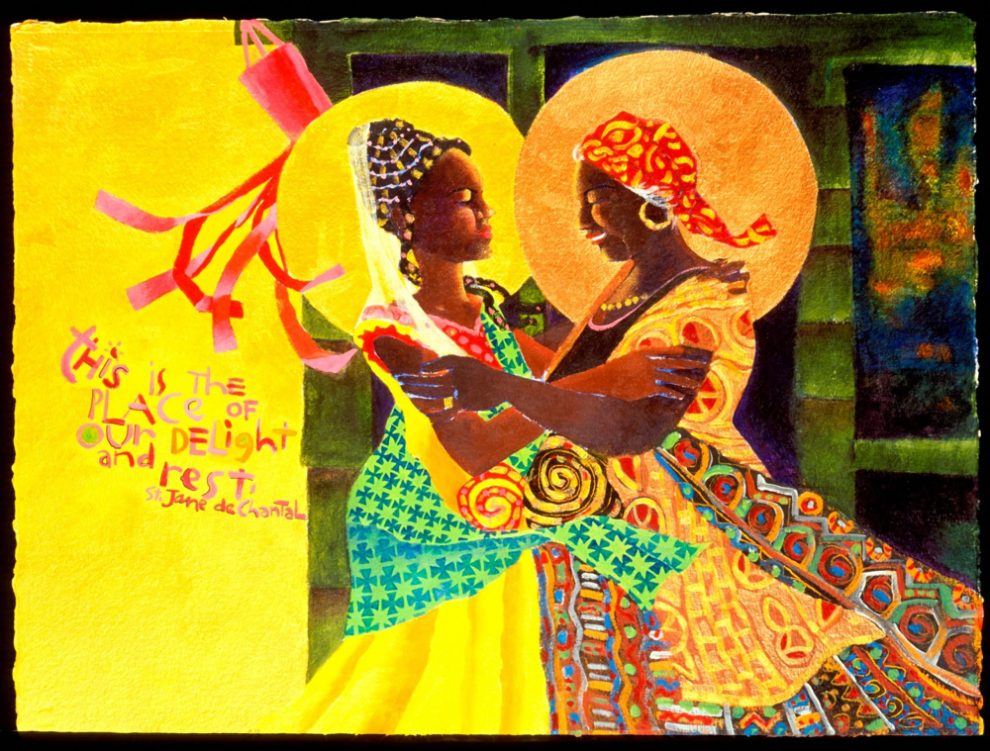

Indeed, McGrath’s love for Blackness specifically is evident in various images throughout the text, including the Windsock Visitation of Minneapolis and the BLM Madonna. When looking at his art, I am confident that he recognizes in Black and Brown bodies what Elaine Scarry coins the four features of beauty: (1) It is sacred; (2) it is unprecedented [unique]; (3) it is salvific; and (4) it is intelligible. The gift of McGrath’s Madonnas of Color is that Catholic hearts and imaginations are reoriented to the beauty and sanctity of Black and Brown bodies, bodies that for too long have been discarded and dehumanized. May all who encounter the different shades and hues of these Madonnas come to recognize the divine within each of these images and the bodies they so keenly represent.

All images: © Michael O’Neill McGrath, OSFS / www.bromickeymcgrath.com

Header image: Windsock Visitation, from Madonnas of Color, by Brother Mickey McGrath

Add comment