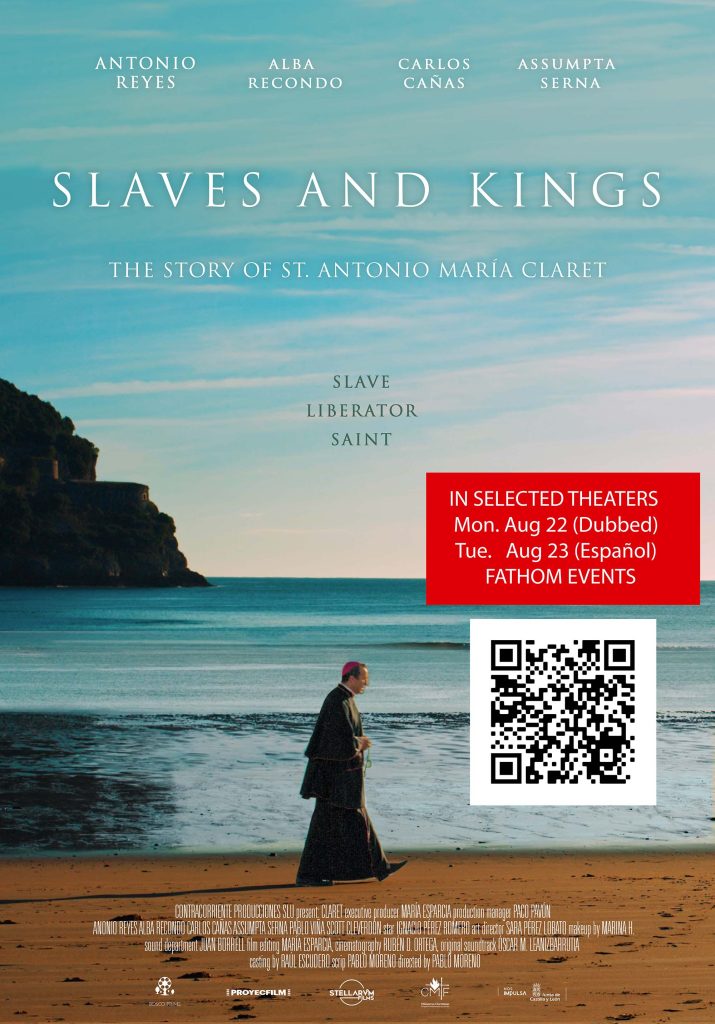

Slaves and Kings

Directed by Pablo Moreno (Bosco Films, 2022)

The Spanish-language film Slaves and Kings is subtitled “The Story of Saint Antonio María Claret.” As the subtitle clearly indicates, this film invites historical scrutiny (in Spanish, the words story and history are identical). The story is intended to function as a correction to popular histories of St. Claret and as a positive introduction to his life. I am not a historian, much less an expert in 19th- and 20th-century Spanish history, so my remarks should also be taken with some degrees of caution. It does seem worth noting that an authorized autobiography of Claret is widely available in Spanish and as an English translation.

The film is driven by a double plot, a classic “story within a story,” narrated by a secular Spanish intellectual and author, Azorín, who finds himself immersed in studying the life of Claret. Arozín is motivated, in part, by a visit from a Claretian priest seeking to advance Claret’s cause for sainthood.

This 20th-century plot line narrates the story of Claret from his time as a weaver to various stages of his life as a seminarian, young priest, archbishop, and confessor and counselor to the Queen of Spain. In the film’s final biographical note, the film notes Claret’s attendance at the first Vatican Council just before his death in 1870.

The arc of Claret’s conversion is portrayed in his initial inability to forgive a friend who wronged him, which propelled him into the priesthood, to eventually forgiving a hired assailant and having the man’s death sentence commuted.

The political environment of the Carlist Wars is palpable in Claret’s young priesthood; the film identifies him as a Carlist while also showing him caring for a wounded Liberal soldier. Claret’s place in an overtly political social context while eschewing politics himself begins in this period and is a theme that continues throughout his life. The Liberal value of books, disclosed by the wounded soldier, is framed as a motivation for Claret’s authorship of devotional texts.

The film describes Claret during his tenure as Archbishop of Santiago, Cuba as an abolitionist willing to invoke Spanish and church law—including excommunication latae sententiae—upon those who practiced enslavement. He worked actively to marry interracial couples, openly noting how Spanish men often abandoned their children born of enslaved Black women.

The film portrays Claret as caught between a throne and altar in Spain and Rome that are morally skeptical of enslavement and located just south of chattel slavery in the United States, with strong business interests for annexation. This political context informs a complex kind of abolitionism where Claret, an archbishop appointed by the Catholic Queen of Spain, intervenes on behalf of enslaved people and faces violent threats and assault as a result but does not play a direct role in the abolition of slavery in Cuba (which would not come until 1867).

The film portrays Claret’s exit from the Caribbean as a triumph of his influential enemies who at one point describe his fate as enslavement: An unfortunate phrasing that seems to operate in the film’s title. A presentist but macabre reference to Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” yields a harrowing lynching scene that punctuates the difficult kind of apolitical abolitionism the film portrays Claret as championing. Claret’s return to Spain is emphatically due to obedience, not choice, including a note of skepticism about the proximity of the Spanish throne to the Roman altar.

The remainder of the film is predominately focused on the relationship between Claret and Queen Isabella II, first as her confessor and then, in a rebound after Isabella recognizes the secular Italian state against papal state interests, as her counsellor. Claret only accepts his role as confessor to the Queen on the condition that he live outside of the royal palace and be allowed to work in the community without royal luxuries such as transport.

Claret continues to be a divisive and controversial figure, trying to remain apolitical amidst relationships of church and state that are intentionally political. When Claret’s revolutionary opponents finally pressure the Queen to recognize secular Italy, we glimpse Claret’s political allegiance to the papal state as he not only terminates his post as her confessor but also advises her of the canonical consequences of her offence.

His enemies’ second removal of Claret is short-lived when Claret eventually returns as the Queen’s adviser and founds a seminary and school while she also consults him on major ecclesial appointments. As public sentiment against the Crown increases, Claret goes into exile with the Queen. (At this point, this plot aligns with the narrator’s secondary plot as Azorín goes into exile with his wife.)

Claret’s enemies do not rest when he is exiled. They plan to destroy his memory by publishing a distorted biography. Likewise, in the narrator’s plot, Azorín finally chooses to publish his article in Argentina’s La Prensa and finds his love rekindled with his once-estranged wife. Azorín’s article serves Claret’s canonization in 1950.

When Azorín chooses to publish his article, he mentions that he may, as a result, be seen as sympathetic towards Francisco Franco. Franco’s wife, Carmen Polo, attended Claret’s canonization and was granted an audience with Pope Pius XII. This final note is not included in the film, but it seems worth noting because there is a profound tension that is mirrored by both Spanish historical plots and is also at work in Claret’s life and thought.

For example, despite Claret’s apolitical self-characterizations, he lived in an environment where he had to resist being a political pawn and often made consequential political moves of his own. In his own autobiography, he wrote, “The Lord has made me know the three great evils that threaten Spain and they are: Protestantism, or better yet, the discatholization of Spain; the Republic and Communism.”

This film’s motive is clearly not to engage with these tensions, and it often suffers from romanticism and presentism, but it does succeed in illustrating the tense and difficult political history of the Catholic Church in Europe and the Americas, including the struggle for and against colonialism, slavery, and reactionary political movements such as fascism. Bringing this story to the English-speaking world is a contribution to the reform and renewal that Claret so fervently desired to see.

Image: Bosco Films / Stellarum Films

This article is also available in Spanish.

Add comment