December feels like the soft landing every year could use. While January is often propelled by a crazed monster of executive function—New Year’s resolutions, goals and budgets, new semesters and scheduling!—the end of the year generally drifts through gentle, benevolent hours like a hushed twilight snowfall. January stares forward and plans. December gazes backward and reminisces.

We who celebrate Advent define these weeks as a beginning nonetheless, though this fresh church calendar has none of the energy and ambition of a secular new year. During Advent we simply sit in the dark—and wait. Like seeds buried in soil, we anticipate the new life that will emerge from this apparent inactivity. Waiting, after all, isn’t the same as doing nothing. Waiting involves an expectancy that something is coming, that change is possible, that a transformation of the present reality is just around the corner and may be closer than we imagine.

Waiting is, essentially, an act of hope. Those in whom hope has been extinguished expect nothing more than more of the same.

At the end of another long year of sickness, when a return to normalcy still feels elusive, another season beckoning us to be patient may be a little harder to embrace than usual. The streets still feel meaner than we want them to feel. The cautious way we’re obliged to live for the holy sake of each other is getting threadbare. Another day of masking up. Another shot in the arm. Another hesitation at the sight of a stranger and the reflexive mental measurement of the space between you and them. All of this takes its toll.

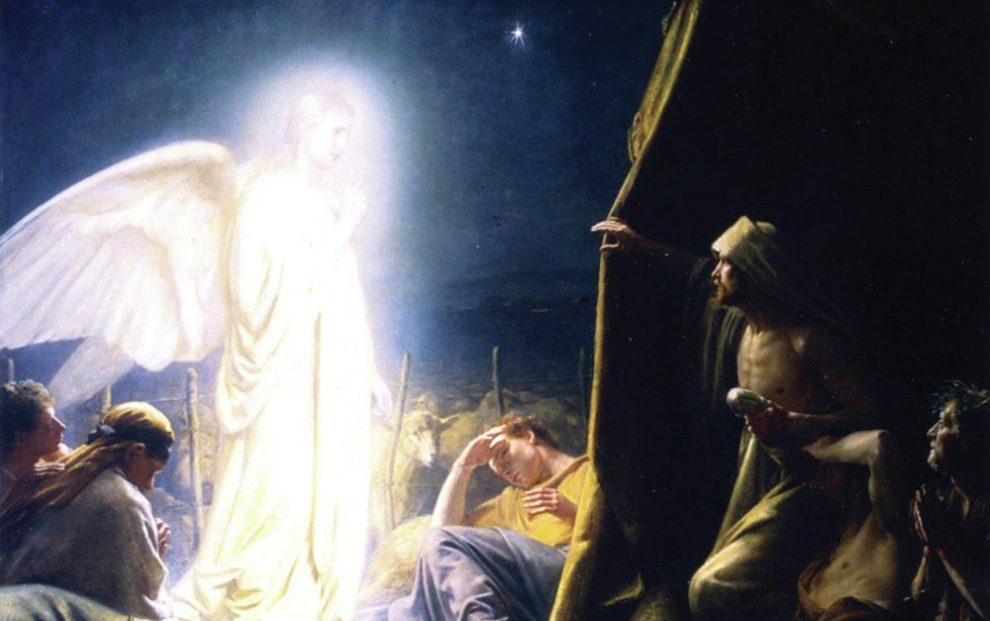

Advent is a reminder that, while you and I may be sick and tired of caution and risk, God isn’t giving up on humanity and its possibilities. “Do not be afraid,” the angel will soon declare. “I am bringing you good news of great joy for all the people.” Those who carry the burden of fear the way Atlas mythically carried the world on his shoulders may well be skeptical of this claim. We literally carry a world’s worth of fear these days: climate change, global terrorism, wars, floods and fires, economic anxiety, clashing politics, social violence, and age-old plain vanilla bigotries. Add in any personal relationships in jeopardy or physical frailties of your own. It’s easy for an angel to take fear off the table. Angels don’t stare at the ceiling all night worrying about the future.

Yet the cosmic promise hangs in the air. Good news of great joy is on the horizon. For everybody, no less. How in the world—how in this world—is that even plausible?

Advent people gear up for the improbable, the unlikely, the gosh darn near impossible. Because let’s face it: Good news for everybody is about as conceivable as virgin birth or God walking in our shoes—should we be fortunate enough to have a pair. Yet an angel hereby pledges that overwhelming celestial joy has arrived to remove the terrible dread from our backs and to replace it with an extraordinary lightness of being. Are you and I truly waiting for this? Are we making room for the advent of something as new, and as necessary, as a future without fear?

Waiting is, essentially, an act of hope.

Advertisement

Some of us, it has to be said, prefer to cling to the familiar, even if it means our present anxiety or deep pessimism about the future. The rationale behind this choice goes something like this: I can’t be disappointed if I expect nothing more from life, leadership, or tomorrow. It’s a stance too many people are taking. Digging our heels into history’s serial disappointments or being convinced that our scars tell the whole story about what’s likely to come is an option, of course. But that’s not what Advent people do. We’re seeds. We’re waiting in joyful hope for a transformed reality: not for the next dismal shoe to drop.

What do seeds do while they wait? They’re hardly asleep. In fact, they’re making incremental changes every moment. Seeds nourish themselves in the dark for the future that will summon them to a remarkable new reality. Seeds expand and divide, preparing for the tomorrow that’s coming. They bide their time, seeking optimal conditions for survival before they make their move. Then comes the risky part. Seeds break open, abandoning their protective shell and emerging vulnerably into a future that transcends everything they

knew in the past.

We hear friends and family say all the time: I want the world to go back to how it was. I want the life, abilities, and opportunities I used to have. I want truth to remain what I was taught years ago. I want old practices and values—and yes, even old standards of judgment and prejudice—to be restored to me as normative. I don’t want to adapt to new information, to expand my thinking, to grow up and out of my comfort zone.

Seeds that remain in the dark and never face the risk of leaving the shell have no life in them. Honestly, even a rock surrenders to the elements of change: heat and cold, pressure and release, wind and water and time. If you and I have the vitality God gave a stone, we’ll bow to the necessity of transformation. Yet we’re called to be more than stones. Much more.

Advent people gear up for the improbable, the unlikely, the gosh darn near impossible.

An angel announces the arrival of good news of great joy for everyone. It’s real and it’s happening, but it demands that we be present to it. The shepherds on a Bethlehem hillside who first received this proclamation might have shrugged their shoulders, stayed put with their flocks, and by doing so never became the possessors of that joy for themselves. The magi might have observed a new star rising in the east, marked it on a papyrus chart, and gone home to their suppers, never seeking the new king or bringing their gifts. A daughter of Nazareth may have waited out the angel yammering on about God’s favor and divine overshadowings, only to reply: Heavens, no, you’ve got the wrong girl. A carpenter might have divorced her quietly. Any one of us can refuse to emerge from the shell we’re presently in because we’re comfortable here and the world out there is fraught with danger. And in the grand scheme of salvation history, our choice matters.

Advent darkness is a quiet, cozy place in many respects. We may frankly appreciate the absence of penitential feeling and obligations to fast in this final yet first season, in a cross-section of time between secular and sacred calendars. We enjoy cheery carols and merry lights, social traditions of giving and receiving gifts, which, by doing so, express love and gratitude to people we may fail to visibly celebrate the whole year through. The glitter and sparkle of seasonal decorations and gatherings make the routines of living seem for a time special and wondrous—which indeed they are.

Yet underneath the familiar Advent rituals observed by church and family, that unpredictable seed is sleeping, harboring its precious and challenging new life. Don’t be afraid, the angel invites us. The wild newness coming can’t be imagined or contained, tamed or controlled. But the world needs this new life to bring light to its darkness, a way through its madness, a truth to dispel its comfortable and convenient fictions. The news is only good if it’s good for everyone. Joy is only lasting if it wipes away every tear. Merry Christmas.

This article also appears in the December 2021 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 86, No. 12, pages 47-49). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Wikimedia Commons/The Shepherds and the Angel, Carl Bloch, 1879.

Add comment