In my years of counseling, teaching, and working alongside Catholics of all ages through parish work and hospital chaplaincy, I’ve come to realize that a nontrivial number of individuals from our faith tradition have an uncomfortable—if not downright problematic—confession story.

Here’s mine: Just as I was beginning my semiannual, school-sponsored sacrament of reconciliation circa 2002, the priest held up one finger as if to signal “this will only take a moment,” reached into his alb, whipped open his vibrating flip phone, and urgently exclaimed, “I’m hearing confessions. Call you back in 20 minutes!”

Banging his phone shut, he returned his gaze to me and equally urgently commanded, “Tell me your sins, my child!”

I was taken aback—our teachers never answered their phones in the classroom—and skeptical. Twenty minutes? Had he not seen the long line of seventh graders behind me? Or was he that optimistic about what a seemingly harmless gaggle of East Coast adolescents could possibly disclose?

One thing was for sure: I wasn’t about to confide anything that was actually troubling me to this priest. Sensing his shortage of time, patience, and care, I spent that confession prattling off a benign list of faith-related misdemeanors that had little bearing on my development of moral conscience. The priest absolved me of my sins, and I was out the door in 2½ minutes, keeping him on track to wrap up as expected, so long as his brother priests in the neighboring confessionals maintained the pace.

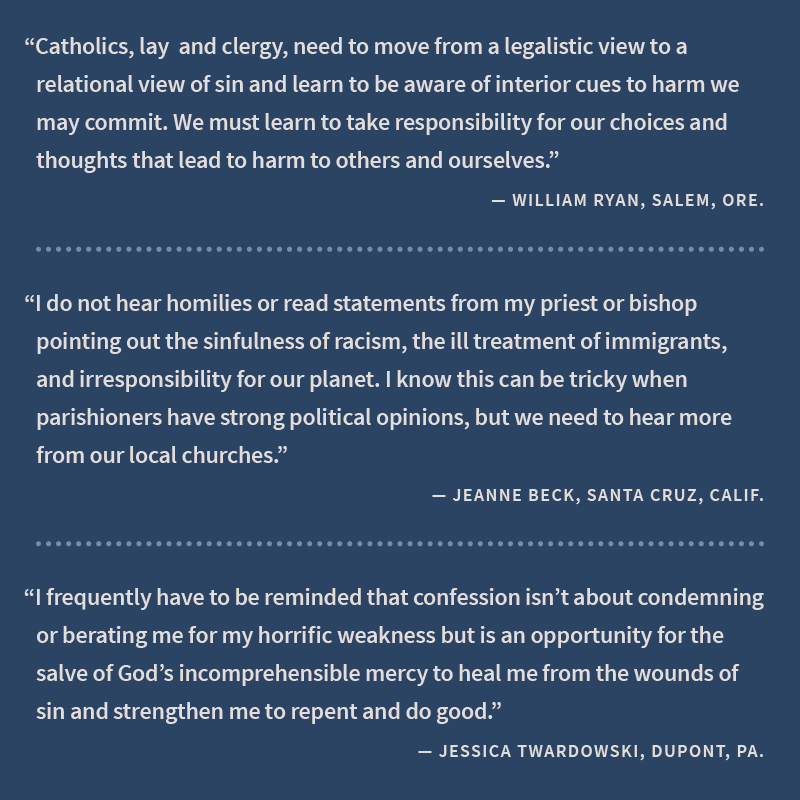

Although I’m quick to point out the flaws that come with the sacrament as the Catholic Church celebrates it—and I tend to lean Protestant in my belief that acknowledging our sins before God is enough to receive forgiveness—I’m actually not opposed to the practice of confessing sins to a priest. The sacrament institutionalizes a time to examine our hearts and name where we’ve fallen short. The practice forces us to take a good, long look at ourselves and consider, with the help of a spiritual guide, where we could be doing better. If done correctly, confession keeps us humble and growing.

The sacrament loses its potency, however, when rote action replaces reflection and we fail to actually examine our recent words, thoughts, and actions with any level of depth. Regrettable confessional experiences like the one I described lead to a less-than-useful approach to the sacrament of reconciliation. So does an unexamined and rigid view of sin.

For example, if I think of sin as breaking the Ten Commandments but resist pondering the layers of meaning embedded within the ancient and life-giving moral code, every single one of my confessions could sound like this: I took God’s name in vain when I stubbed my toe. I claimed to be busy to avoid talking on the phone with a friend. I skipped Mass in favor of lounging in bed with a novel. A confession like this demonstrates what I think of as the “bad things we do” model of sin, an understanding that isn’t necessarily wrong but limits our way of thinking about sin and, in turn, limits our way of thinking about goodness. If sin is just a laundry list of wayward behaviors, then is goodness simply the absence of those behaviors? Is a good person someone who never swears and wouldn’t dream of missing Mass? Perhaps. But when I picture that person, I think of Mark Twain describing a character as “good in the worst kind of way.” We all know a person like this. I avoid her.

One of my cousins, as a child and adolescent, tended to get hung up on an idea and obsess over it. My strongest memory of him comes from the summer he spent proclaiming, “There is no darkness! There is only the absence of light!” At the time, I didn’t give his declaration much thought, but apparently it ingrained itself in my mind because it’s what comes to mind now when I think about sin. What if, instead of thinking about sin as “bad things” or darkness, we instead think of it as the absence of light or the absence of love?

Sin isn’t the hissed “Goddammit” so much as it is the carelessness and lack of love with which I invoke the name of our Creator any time I’m frustrated. Sin isn’t the few words I shoot off in a text: “Can’t talk now. How about next week?” It’s the absence of care I’m showing toward my friend in her moment of need. Sin isn’t the extra rest on a Sunday morning. It’s the failure to demonstrate commitment to my community and gratitude to God.

This shift in thinking about sin, far from giving us a free pass to do as we please, summons us to ponder more deeply our actions, relationships, and emotions. Goodness isn’t about checking boxes. It’s about pruning our hearts so that they slowly but surely conform to the heart of God. It’s what Jesus was calling the young man who had “kept all [the commandments] from [his] youth” (Matt. 19:20) to do when he told him to sell all his possessions and follow him.

Adjusting how we understand sin asks a lot of us, both in terms of rigorous self-examination and accordingly changed action. When considering, say, the seventh commandment not to steal, it means not patting ourselves on the back because we don’t shoplift but instead examining our consumption and comparing our lifestyle to that of the rest of our human family. Honestly assessing whether we take more than our share in terms of global resources is painful, to say the least.

Or consider the eighth commandment not to bear false witness: It’s one thing to phrase our words in a way that we never tell a lie, but it’s an entirely different thing to earnestly seek and lovingly speak the truth (which, by the way, doesn’t include firing off angry tweets or dogmatically voicing our opinions to anyone who will listen). Truth seeking involves asking questions, admitting biases, and becoming aware of blind spots. Truth speaking requires listening closely, integrating seemingly dichotomous ideas, and discerning whether our voice will contribute good to—versus merely add to the cacophony of—the public discourse.

It’s easy enough to sit down in a confessional and rattle off the times we skipped Mass, disrespected our parents, or looked longingly at someone else’s possessions. It’s a lot harder to ask ourselves, “Where was my love incomplete? When did I put care for self above care for others? How did my thoughts, words, and deeds fall short in following the path of Jesus?” But if we can think of sin in this broader way, if we can look at sin not as the bad things we’ve done but as the instances where love was lacking, well, that’s when we grow and evolve. That’s when we move in the direction of becoming the people whom God created us to be.

This article also appears in the October 2021 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 86, No. 10, pages 25-30). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Unsplash/Josh Applegate

Add comment