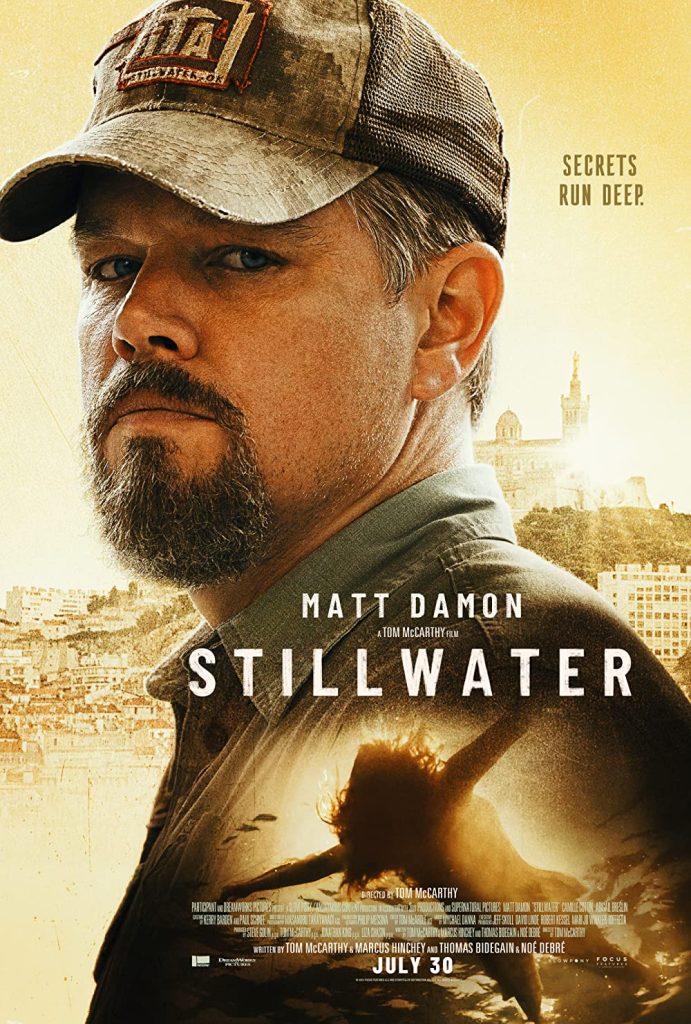

Stillwater

Directed by Tom McCarthy (Participant, 2021)

Stillwater opens to the roar of demolition, a quick montage of heartland decay as Matt Damon’s Bill Baker, a laconic oilman and addict, helps a crew take down the American dream one abandoned building at a time. The Oklahoma landscape makes us brace for yet another Hollywood take on Trump-era Red State despair, only for the plot to whisk us to the south of France, where Bill’s flannel, baseball cap, and work boots stand in stark relief to director Tom McCarthy’s shots of Mediterranean architecture and crystalline coasts.

No tourist, Bill works jobs on the plains to save for visits to his daughter, Allison (Abigail Breslin), imprisoned in Marseille for the murder of her girlfriend while studying abroad. There’s more that separates the two than bulletproof glass: Allison left their small town to go as far away as she could. Newly cosmopolitan and fluent in French, she embodies a caged desire for forward motion and change, sharply paralleled with Bill’s clumsy attempts to impress himself on the culture.

The driving narrative thrust of the film is Bill’s quest to prove his daughter’s innocence. This is also where it is strongest; we feel his growing helplessness as he tries to navigate a world where much is alien to him. Help comes in the form of a bohemian actress (Camille Cottin) and her young daughter (Lilou Siauvaud), who welcome Bill into their life after a kind deed. Although given spark by Cottin, this relationship feels cloying and forced. The workmanlike direction is never able to establish a realistic rapport between these divergent characters.

The film endeavors to show the potential for human connection across class and culture, but these themes languish on the surface as the plot descends into implausibility. Ultimately, Bill’s downfall is ingrained individualism, which robs him of what he truly desires. Clumsily handled material does the same for the audience.

This article also appears in the November 2021 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 86, No. 11, page 38). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Jessica Forde / Focus Features

Add comment