On December 2, 1990, soldiers murdered or wounded three dozen unarmed Tz’utujil Indians in Santiago Atitlán, a picturesque, mostly indigenous town of about 28,000 on the shores of Lake Atitlán in Guatemala’s Highlands. What followed was a revolt so unusual that it merits recognition in modern Guatemalan history. Never before had a Guatemalan town succeeded in ousting the army from its vicinity—and the villagers of Santiago Atitlán did so without resorting to violence.

This revolt is inextricably tied to another killing in Santiago Atitlán a decade earlier: that of Stanley Francis Rother, a priest from rural Oklahoma. Throughout his thirteen years as a missionary in their town, Rother had deeply impressed and influenced the downtrodden Tz’utujil by immersing himself in their lives, respecting the beauty and spirit of their culture, and committing himself to their struggle for dignity. In the process, communal and spiritual bonds were forged between the pastor and the people. The priest’s close-knit relationship with the villagers—and his murder—would ultimately play a significant psychological role in what took place in Santiago Atitlán in December 1990.

A Welcomed Presence

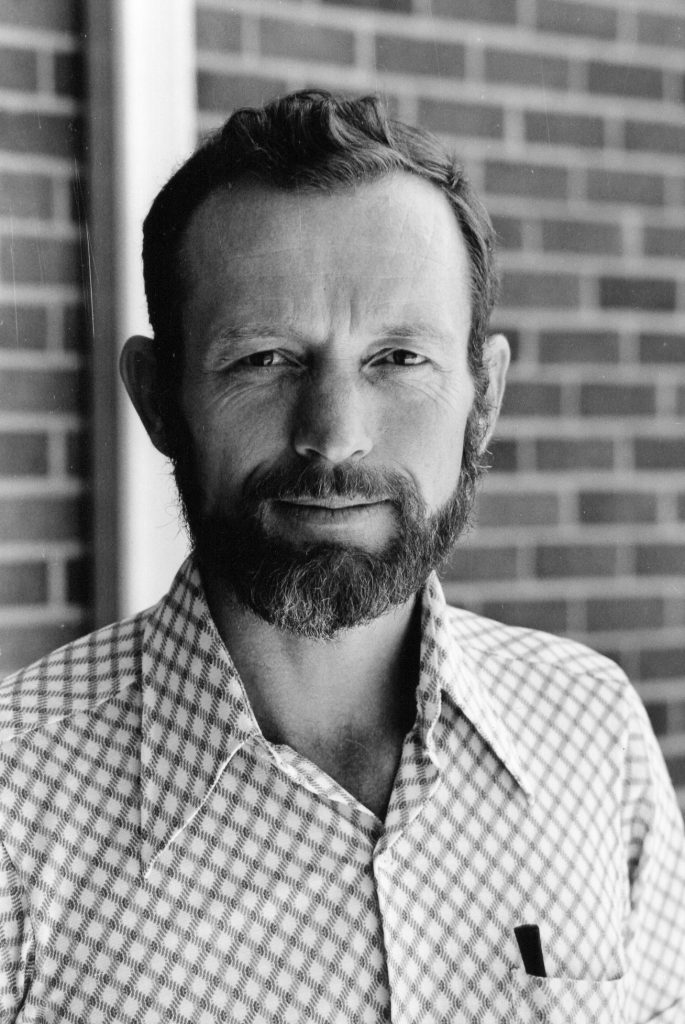

In 1953, a martyr’s death seemed unlikely for Stanley Rother, who struggled with his studies as a seminarian before flunking out. His bishop saw something special in this unassuming farm boy, however, and arranged for him to enter another seminary. Rother persevered and was ordained in 1963, but the ordeal left him feeling inadequate in his priestly ministry. When he was offered the opportunity to serve in Oklahoma City’s diocesan mission parish in Santiago Atitlán in 1968, he jumped at the chance. In Guatemala, he would find the fulfillment that had eluded him in Oklahoma.

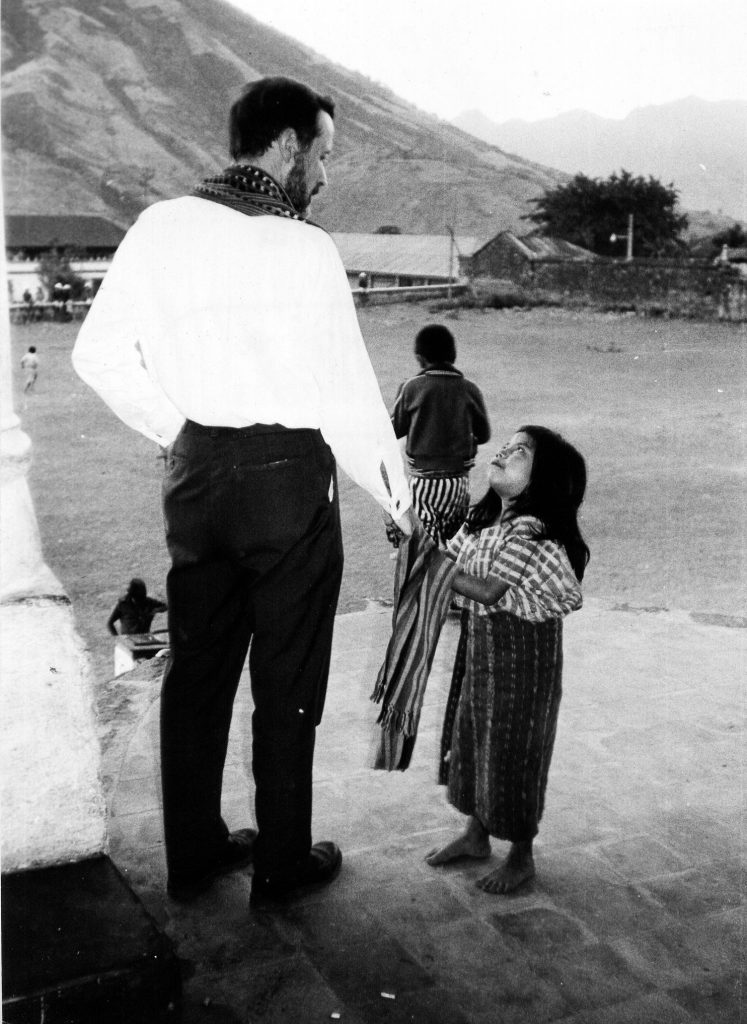

The Tz’utujils were a poor people who survived by growing corn and beans. Rother, a farmer like them, gained their respect by getting his hands dirty while working alongside them. He was indefatigable and applied his considerable skills in carpentry, agriculture, mechanics, and design to benefit the villagers. More importantly, he treasured their culture and religious traditions. The fact that Padre A’plas, as his Tz’utujil parishioners affectionately called him, had actually learned their native tongue—no easy feat for an outsider—cemented their close bond. Soon he was accepted as a trusted and beloved member of their community and even was honored by the cofradía (brotherhood) elders.

This peaceful tranquility began to erode in 1978, and by the early 1980s about 3,000 Guatemalans, mostly Indians, were being murdered every month. At first Santiago Atitlán was spared the carnage. But when the army built a military base on the outskirts of town in October 1980, the Tz’utujils began to die or disappear in alarming numbers. By January 1981, thirty of Rother’s parishioners had been abducted or murdered, and Rother discovered that he too had become a target. By 1990, between 800 and 1700 Guatemalans would meet a similar fate in Santiago Atitlán.

A little after midnight on July 28, 1981, three masked men forced their way into the village’s Santiago Apóstol parish rectory. After a short struggle, the pastor lay dead in a pool of blood. Padre A’plas had been warned that a death squad was on his trail. He might have escaped, but he told his friends, “The shepherd cannot run at the first sign of danger.” Refusing to abandon his people, he fought to the death with the three men trying to abduct him. In 2017 he was officially declared the first U.S.-born Catholic martyr and was beatified.

An Enduring Bond

The relationship established in life between Padre A’plas and the Tz’utujils endured after his death. When grief-stricken Tz’utujils asked the Rother family if the pastor’s heart could remain in Santiago Atitlán, they graciously consented and it was reverently buried in the sanctuary of Santiago Apóstol church.

For almost three years after Rother’s death, Santiago Atitlán had no resident priest. Then, in 1984, Father John Vesey became pastor, but was reassigned due to death threats after only a few months. During his short tenure, however, Vesey transformed the room where Rother had been martyred into a chapel honoring his memory. Later, when the spiritual writer Henri Nouwen visited Santiago Atitlán and entered this chapel, he was deeply moved by what he witnessed:

It may be years, decades or even centuries before the church officially declares Stan a saint, but the people of Santiago Atitlán are not waiting. They have already declared Padre Francisco [Rother]… a saint. They come to him daily and ask for help with their concrete, personal needs. He is one of them, a father, brother, and friend who for 13 years served them on earth and now intercedes for them in heaven. He was their shepherd, he still is their shepherd.

Nouwen’s comments attest to the enduring symbiotic relationship between the Tz’utujils and Padre A’plas. Rother had chosen to remain with them when he could have fled to the safety of Oklahoma. This profoundly affected the Tz’utujils: He had been murdered, as had their own family members and friends.

Father Tom McSherry, Vesey’s pastoral successor, eventually moved Rother’s heart to a more prominent location near the entrance of Santiago Apóstol. Here he erected a shrine accentuated by a plaque dedicated to the Oklahoma priest-martyr. But this was not all: He honored the villagers who had been murdered, covering the shrine wall with metal plates, each of which contained the name of a Tz’utujil victim, and placed a candle in front of each one. Like the chapel, this shrine further entwined Rother with every local indigenous person who had suffered a similar fate.

As violence mounted in Santiago Atitlán in the late 1980s, the Atiteco townspeople lived in fear of the army encamped nearby. Few ventured out after dark and farmers abandoned their milpas (cornfields), most of which were on the outskirts of town, because many of their neighbors had been intercepted and murdered or abducted by army patrols.

But, as Frankie Williams, a frequent volunteer at the Oklahoma mission, remarked in a letter written in 1987, even in the midst of such brutality she could sense a new vitality and pride gradually developing in the beaten-down indigenous people. It was “like watching flowers come to full, perfect blossoms,” she noted.

A Revolt of Solidarity

In 1990 a small band of guerrillas moved into the Lake Atitlán region, and the military used this excuse to double down with their cruelty. On the evening of December 1, a drunken soldier shot an eighteen-year-old Indian, paralyzing him from the waist down. After ten years of army repression, the Tz’utujils had had enough. Town leaders hurried to the church, where they rang the bells from midnight to 1:00 a.m., calling Atitecos to assemble. After a crowd of about 3,000 had formed, the villagers marched peaceably to the military base, about a mile away. Carrying white flags, they shouted, “Get out, army! We want to live in peace!” As the mayor tried to speak, soldiers suddenly fired on the unarmed crowd, killing fourteen and wounding twenty-one.

But the villagers refused to be intimidated. They formed a human chain that encircled the base, so that no one could leave or enter. About 20,000 Atitecos signed or put their thumbprint on a petition to President Vinicio Cerezo, demanding justice and the closure of the military base. National elections were on the horizon; Perhaps for this reason the president immediately dispatched his human rights procurator to the scene of the massacre.

Expecting the usual whitewash, Atiteco leaders found a foreign photojournalist, who took graphic photos of the victims. They were immediately sent out on news-wire service, along with her commentary. Simultaneously, Voice of Atitlán Radio broadcast the truthful account of the massacre throughout the region.

When the procurator’s report appeared five days later, it placed full blame for the massacre on the army. Never in modern history had the Guatemalan government taken such a bold action.

Soon after the report was issued, the usually unassertive Guatemalan Congress unanimously called for the army to withdraw from Santiago Atitlán and for the perpetrators of the massacre to be punished. On December 20, less than 20 days after the massacre, the army left, never to return.

The Atitecos, however, still had work to do. They devised a blueprint that placed the responsibility for policing Santiago Atitlán in their own hands and it proved to be remarkably successful. As Father McSherry would later attest, villagers again came out on Friday and Saturday nights, farmers returned to their fields, and since December 1990, virtually no serious violent incidents have taken place.

Today in Santiago Atitlán there stands a “Peace Park” where the Tz’utujil massacre took place. Prominently displayed is a stone replica of President Cerezo’s declaration that forced the army to withdraw. The park holds a cross for each of the victims and every year on the anniversary of the massacre Atitecos gather there to celebrate a memorial Mass.

Most Atitecos still live in dire poverty, but due to their own persistent and assertive non-violent efforts, they at least live without fear of military death squads. Although it cannot be verified, there is little doubt that the Atitecos’ memory of their beloved Padre A’plas, coupled with their continued connection to him well after his death, were factors in empowering them to confront the army which had persecuted them for ten long years.

Perhaps it is no coincidence that Rother was officially declared a martyr by the Catholic Church on December 2, 2016, exactly twenty-six years to the day after the Tz’utujil revolt. Perhaps this is a sign that Padre A’plas was still with his people even after his death, when they cried “Enough!” and successfully stood up to demand that they be left to live their lives in peace.

And just as Rother helped inspire the Tz’utujil to stand together in solidarity, their victory in 1990 inspired several other indigenous towns to force the closure of their local military bases. Perhaps he and the Tz’utujil people can inspire that same sense of solidarity in us as well.

Images: Courtesy of Donna and Ed Brett

Add comment