“Good book. Did you know he was Catholic?”

You never know what questions will mark you for life, but there was no doubting the impact of this one. I had just walked into a required theology class the fall semester of my junior year. On top of my schoolbooks I had Black Elk Speaks, which I had been rereading for fun.

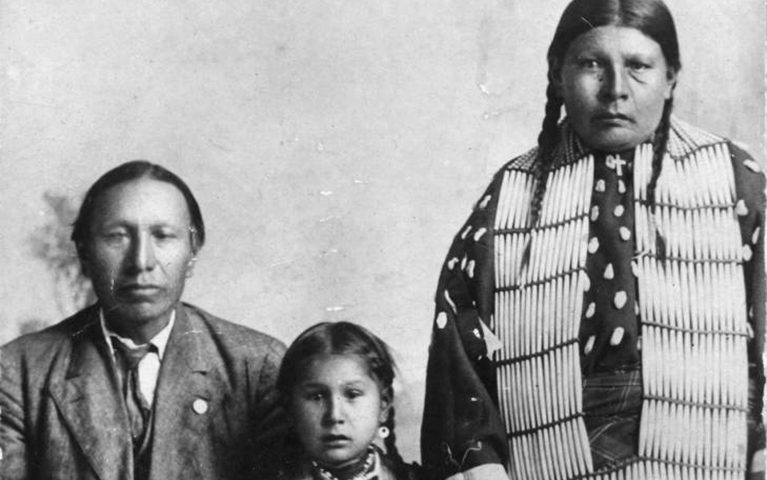

Catholicism was about the last thing I would have associated with Nicholas Black Elk. Like virtually everyone who has read the book since it was published in 1932, I read it because it is a beautiful Native story about a Lakota boy growing up hunting buffalo on the plains during the so-called Sioux Wars. At 9, he was given a great vision of the sacred tree with the calling to save his people. Black Elk recounts epic battles and miraculous healings and introduces the larger-than-life figures of Crazy Horse, General Custer, and Sitting Bull.

A prophet for his people

A big part of the book’s lasting influence is how the drama of Black Elk’s early life seems to so perfectly capture the whole drama of Native American history. The book makes the 1890 Massacre at Wounded Knee the final exclamation point of a continentwide tragedy. It then skips Black Elk’s adult life and leaves the reader thinking he was a broken old man lamenting the sacred tree that never bloomed. Through this image and the book’s epic tone, Black Elk became a kind of prophet that spoke to the seemingly intractable global problems we face now. I read my angst and fury into the story and saw it all through Black Elk’s eyes.

Above all, the authenticity of Black Elk’s spirituality spoke to me—the power of his great vision of the renewal of all peoples and his unending quest to live up to that calling. I found Black Elk’s other book, The Sacred Pipe (University of Oklahoma Press), an account of the seven sacred Lakota ceremonies, and it taught me about Lakota spiritual traditions. More important, Black Elk portrayed an authentic relationship with God outside of my usual stereotypes and spoke directly to an only partially identified spiritual longing: Black Elk connected deeply with every facet of creation.

My professor encouraged me to do a senior project on the topic. How could Black Elk be Catholic and Lakota at the same time? I embraced this educational opportunity like never before. I read everything I could find, completely immersing myself in the topic. In the process, I discovered a number of unexpected things about Black Elk.

How could Black Elk be Catholic and Lakota at the same time?

Black Elk’s Catholicism

First, Black Elk was thoroughly and completely Catholic. After his baptism in 1904, he taught himself to read the Bible in Lakota. Because of his zeal, the Jesuits appointed him to the position of catechist, which in Black Elk’s community functioned much like a permanent deacon does today. He became famous for memorizing scripture and weaving passages into his oratory. He was a long-term missionary to other tribes and is credited with bringing over 400 people into the church.

Black Elk’s Catholic faith had a traditional hue that I didn’t expect. Devotions, such as the rosary and Sacred Heart, were important to his prayer life. Black Elk loved the Latin liturgy and sang his grandchildren to sleep with Latin hymns from the high Mass. He was comfortable weaving these into his Lakota spirituality, not replacing it.

What I saw then and even more clearly when I continued the project in graduate school was how Christianity addressed questions about the colonial situation the Lakota people faced. Black Elk wasn’t the broken old man that Black Elk Speaks portrays, and the Lakota world didn’t end with Wounded Knee. The Catholic faith, despite the church’s participation in the colonial oppression of the Lakota, was a key ingredient to proactively survive the upheaval.

On the one hand, Catholic teaching gave Black Elk’s faith a new standard of justice to hold the invaders accountable. On the other, Black Elk’s faith gave him the framework to understand the invaders as human beings suffering from similar issues as the Lakota did and to reinterpret traditional Native enemies as sisters and brothers in Christ. “We all suffer in this land,” Black Elk writes of the Lakota, former enemy tribes, and settlers in a 1909 pastoral letter. “But let me tell you, God has a special place for us when our time has come.”

Black Elk’s Catholic faith had a traditional hue that I didn’t expect.

Advertisement

Protecting his Lakota tradition

It wasn’t until unexpectedly finding myself living in Indian Country that the full depth of Black Elk’s witness emerged. The final stage of his ministry was the revitalization of Lakota tradition. Lakota ways had been under assault by boarding schools, grinding poverty, American culture, and even the church circles he so eagerly embraced. The devastating effect on the younger generations was becoming clearer. Near the end of his life, Black Elk gathered the elders to help find new ways to pass on Lakota lifeways.

Part of the revitalization process was The Sacred Pipe. For almost everyone who first reads it—including me—the book appears to be a straightforward description of the old buffalo-hunting days. Dig deeper into Lakota tradition and you see how different The Sacred Pipe, a product of decades of theological reflection, is from earlier accounts. Black Elk subtly reread the tradition in light of Christ: smoothing out the problematic aspects of Lakota tradition to gospel standards and infusing the practices with a rich Christian spirituality of a loving Creator. Together, Black Elk’s Catholic writings and The Sacred Pipe form a unified vision of all that is, something like Thomas Aquinas’ Summa for Native Christianity.

Black Elk states his purpose for The Sacred Pipe right up front: “God sent to men His son [to bring peace]. . . . This I understand and know that it is true.” After this clear affirmation of his Catholic faith, he explains why we should all know the “greatness and truth” of Lakota tradition: “to help in bringing peace upon the earth, not only among men, but within men and between the whole of creation.” That’s what I saw in the living traditions of Indian Country.

He was comfortable weaving these into his Lakota spirituality, not replacing it.

Advertisement

Cause for canonization

Black Elk’s cause for canonization began in 2017 and is now at the Congregation for the Causes of Saints. Not all Lakota fully support Black Elk’s possible sainthood. A good percentage do, many in a straightforward Catholic way. Some add a particular Lakota twist, such as in relation to the mountain that now bears Black Elk’s name. A two-year campaign to change the highest peak in the Black Hills to Black Elk Peak was finalized in 2016. The catalyst, Lakota Catholic elder Basil Brave Heart, sees the canonization and the name change as two sides of the same living spiritual presence: Black Elk’s vision of the sacred tree extending out into the world.

Declaring Black Elk a saint is not just to rubberstamp what happened in the past but is an event that changes the church and the whole world: a deep affirmation of Native ways that will help bring us back to our spiritual center and a step toward righting the wrongs that structure our world.

Click here for a free documentary about Black Elk’s life and legacy: “Walking the Good Red Road- Nicholas Black Elk’s Journey to Sainthood.”

This article also appears in the May 2021 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 86, No. 5, pages 45-46). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Add comment