We like to think that there are deep, internal, and existential reasons why people convert, but Stacy Davis, professor of religious studies and theology at Saint Mary’s College in Notre Dame, Indiana, says that is not always the case. A variety of events and experiences cause people to reevaluate their lives.

Davis’ theories about conversion come from Lewis R. Rambo’s Understanding Religious Conversion (Yale University Press), which she has taught since 2003. Something we don’t think about often is conversion as the process of intensifying the faith you already have: the prophet Moses in the Hebrew Bible who never stops trying to do God’s will; the Trappist monks in Of Gods and Men who decide to stay in Algeria during the civil war; Chimamanda Adichie who in an article for the Atlantic explains how she disengaged from Catholicism but then reclaimed it upon seeing how Pope Francis prioritizes compassion.

The concept of conversion also explains how people and communities grow and change in ways that might not always be considered religious, because, as Davis says, “life events and world events should change how you view the world.” From whether or not to wear a face mask during a pandemic to how we individually and collectively think about movements like ecological and racial justice, convictions shift due to conversion processes at play—as long as we’re open to learning from one another.

What is conversion?

Conversion is a change in how someone sees life, faith, and/or God. If someone is baptized as an adult, that would be a conversion event, but how someone remains part of a tradition or changes or shifts traditions is a conversion process as well.

In the Catholic tradition, the Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults (RCIA) is a process: You take classes, attend services, and receive spiritual direction. The event of confirmation is the culmination of a process; it’s not actually the conversion itself. While RCIA ends with initiation into the church, the conversion process does not end. If you are the same person 30 years after confirmation, you didn’t do all you could to be formed in the faith.

One common way people convert is what’s known as intensification, which means you become more or less committed to your current tradition. For traditions that are theistic—Islam, Judaism, Christianity—there’s an idea of a relationship with the divine, and relationships are not static. They progress. If a marriage stays the same for six years, that may not be the best thing, because people grow and change. You shouldn’t want to be in the same place you were six years ago.

In an Atlantic article titled “Raised Catholic,” Chimamanda Adichie starts off by saying she was raised Catholic and it didn’t work out, but then she hears about Pope Francis and sort of reclaims cultural Catholicism. She’s saying she may not be practicing, but Catholicism is a part of her heritage, and she’s pulling for this man. If she steps foot in a church again, it’s going to be because of him.

That’s conversion. Even if we move away from something or aren’t practicing regularly, what shapes us is what shapes us.

What’s the difference between conversion and just changing your mind?

The difference depends on the reason for the change. If you start recycling because you are concerned about the trash piling up in your house, that would not necessarily be a conversion.

If you start recycling because you read that plastic ends up in the ocean; whales eat it and it gets stuck in their blowholes; your tradition says, “God created all things and behold they were good”; and you decide it is probably not in your best interest to do harm to God’s good creation, then that is a conversion.

In other words, it’s not so much what you do but why you do it.

Is it OK for someone to be content in their faith, or are conversions necessary?

Conversion operates on two levels: the individual and the group. Group norms are going to be different than individual ones. For Catholics, I’m not sure the expectation would be that you need to keep growing in the tradition in the strict sense of the word. Once you have been confirmed, as long as you are going to Mass regularly and maybe hitting up reconciliation occasionally, you’ll be fine.

If you are the same person 30 years after confirmation, you didn’t do all you could to be formed in the faith.

Advertisement

If you are Southern Baptist or evangelical, there are different expectations about conversion. There’s talk about backsliding and the need to recommit. There are actual liturgical processes, if you can call them that, for recommitting to a tradition that I don’t think Catholicism has.

Buddhists would say you don’t necessarily have a recommitment process. You can be a temporary monk or nun and have an intense retreat process, but then you go back to your life.

So, it depends on the tradition.

Is conversion ever a bad thing?

If a conversion does not lead to greater maturity, if the group asks you to cut off yourself from your family, or if you start concluding that everyone else is crazy and you’re not, that’s unhealthy or coercive conversion.

One example would be Jim Jones and his Peoples Temple, which in the 1970s was really doing quite progressive work in terms of racial justice and class issues. As Jones became more unstable and people followed him to Guyana and then got trapped there, that became an unhealthy conversion. By the end, these folks were willing to drink cyanide-laced punch because they thought this was what they were supposed to do. Hundreds and hundreds of people died as a result.

A more recent example is Lori Vallow, who joined an evangelical cult and apparently thought her children were zombies. Her children are now dead.

We don’t have many examples that extreme, but the presence of community is important. I would be concerned about any tradition that says you need to cut ties. We can have disagreements, but beware of any tradition that says you need to cut off family and friends.

Does the religious language of conversion get misused by secular movements?

All language is designed to persuade. Words have power. They’re not value neutral. You can easily manipulate religious language to say you must do something or must not do something. It is dangerous when someone says, “I have religious sanction for the position that I hold.”

For example, I will go to my grave saying that leggings are not pants. You cannot persuade me otherwise. I’m allowed to hold that view, but if I start saying, “I have heard from the Lord based on this verse here that leggings are not pants,” that’s problematic. In this country, we do that a lot. We tack religious language onto something that really isn’t religious at all.

In many cases what draws a person to a tradition are the relationships and practice, and these have a tendency to precede belief.

Another example is whether or not people choose to wear a face mask during a pandemic. I might think people should wear masks, but I don’t get to argue that there are religious reasons to wear one. I could argue there are ethical reasons. I can make persuasive arguments from a health perspective or even from a perspective of caring for the planet, but I don’t get to say that it’s God’s will. That is where you’ve gone beyond what I think is an ethical use of how to make an argument.

What are some effective conversion techniques?

People are naturally going to become defensive if you start a conversation by saying, “I need you to change your mind.” If you’re trying to elicit a change in people, one of the most effective ways to do that is to simply act. Don’t talk a whole lot. Just do.

The more traditional forms of conversion—like going door to door—don’t work very well. When people tell their conversion stories, often you realize that what appealed to them about a particular tradition is not always the theology but the people. Then they consider everything else.

I teach a class on Christian anti-Judaism. I cannot come out on the first day of class and say, “My goal is for you to realize anti-Judaism is bad,” even though that’s definitely what I want my students to think. Instead, what I have to do is walk them through some resources: Here are the Second Vatican Council documents, here’s the Hebrew Bible, here’s the New Testament. If they reach the conclusion that anti-Judaism is bad, that’s fabulous. If they don’t, no one has lost anything, because they don’t feel like they’re being attacked and I don’t feel like I’m having to preach.

Even with the Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter-day Saints, which is known for going door to door, those who actually convert will say that what appealed to them was not necessarily what they were told on their doorstep. A stronger conversion tool is what are known as family home evenings, where you’re in a smaller group with a community and you make friendships. It’s called affectional conversion. In many cases what draws a person to a tradition are the relationships and practice, and these have a tendency to precede belief.

Pope Francis uses the term ecological conversion in his encyclical Laudato Si’ (On Care for Our Common Home). Why do you think he uses the word conversion when speaking about ecological justice?

The stereotype for a long time has been that the ecological movement is a bunch of atheist tree-huggers. I think what Pope Francis is trying to say is that how you care for the interconnectedness of species is actually a mainstream part of Catholic tradition. He’s using a religious term to argue that part of what it means to be Catholic is to change how you’re viewing the Earth.

Pope Francis uses pro-life arguments in both their literal form and their broadest form to say that people are responsible not just for human species but also animal species. Catholics should be concerned about the Earth precisely because they are Catholic. It’s a way to positively insert religion into the environmental movement.

The pope talks about both interior conversion and community conversion. What’s the difference?

Interior conversion is often how we think about conversion. It’s me and Jesus, me and Allah, me and the Buddha, me and whomever. It is an internal change of heart: I had this particular view of the world or of God, and now I have a new one.

Christianity would not have developed if the original 12 disciples hadn’t each first had an interior change to thinking Jesus is the Son of God and then joined together to start spreading the word.

Christianity would not have developed if the original 12 disciples hadn’t each first had an interior change . . . and then joined together to start spreading the word.

I know a woman who started a food bank in her church. She had to get community buy-in. It wasn’t enough for her to have had this individual moment saying, “Jesus wants me to feed people.” She had to have that change, but she also had to get other people to support that and say, “Yes, and the way we will feed people is to start a food bank in our church.”

The reason you also need the community conversion, particularly when you’re dealing with any type of big social problem like the environment, is that interior conversion is not going to be enough to affect the necessary change. It needs to be a group effort.

I think what Pope Francis is trying to say is that you need the interior conversion, but you also need a group of like-minded people who each have had an interior conversion to join in community and then say, “What can we do?”

Is our society open to conversion?

The historian in me is extremely pessimistic and says maybe not. What’s been interesting over the last 20 years is to see that in many ways the rhetoric is the same. The context shifts, but we’re having the same arguments that we’ve been having since the 1800s. Where my hope lies is in that if we can recognize we’re still having these same arguments from 1830, then perhaps we can have different ones.

Racism, sexism, all of those -isms—they’re old. There are only so many arguments you can make to oppress people. If you can recognize that someone is using the same arguments, then you can come up with different ones. How we can get jammed up as a country is that we are both victims of history and surprisingly ahistorical. We want to act like this is new. This is not new. It’s not new at all. If we can at least say that, then we can start talking about how to deal with the problem.

The idea that we’re all in this together gives me hope for community change.

In 1776 America was arguing that everyone had a chance to be here. We knew when that document was written that wasn’t true, but it doesn’t mean it can’t be now. Everyone is part of a system that they did not necessarily create. The question is not, “Are we mad at one another?” The question is, “How do we make the system better for all of us?”

What does being open to conversion say about how God is present in the world?

Ideally, to be open to conversion means you are open to change.

For me personally, to be open to conversion means that even my pessimistic self has to trust that when people make mistakes, they mean well. It’s seeing people in the best possible light.

The Christian story is that God loved the world even though God knew what the world looked like. After the flood, we get Genesis 8 where God’s like, “Well, people are kind of trifling from their youth, so I can’t wipe them out.” To be open to conversion means that you can’t be God, but you have to at least be able to see people in that same light. They’re kind of trifling, but you can’t wipe them out. There might be something you can learn from someone else.

You have to be open to hearing from others.

Black Lives Matter and community conversion

Are there any cultural community conversions happening today?

The conversation about racial justice in the United States in the last year has been interesting. What has been surprising and hopeful is not so much the sheer numbers but the diversity of those marching. You have young people, old people, people from different ethnic groups. You have LGBTQ groups joining with Black Lives Matter groups. Some parishes and dioceses are talking about what they can do in their communities. The chief of police in Houston stood with marchers.

It’s helpful to see that we don’t have to take a binary approach to this. There are Black police officers and there are unarmed white people who get killed by police. To say “Black lives matter” doesn’t mean cops’ lives don’t. We have a tendency to create these lines, but it’s not a binary.

How are we using language? Talk about defunding the police caused people to lose their minds, but clarifying that it doesn’t mean we want police to go broke and that we simply want to reallocate resources makes it more appealing to people who would have never thought about that concept. “Oh, you mean send more money to social workers? OK, that I can do.” It doesn’t have to tear everything down. I don’t think we can at this point. This country’s too old. You have to work with what you have.

To see older people, younger people, everybody saying, “What can we do?” is positive. We all have different identities, but there is a sense that current justice efforts are not happening in vacuums.

The idea that we’re all in this together gives me hope for community change.

Is this intersectional approach different than what you’ve seen in the past?

I think so. I remember when the Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown decisions came down and the ways in which things were portrayed. When everything happened with George Floyd, in the first couple days I thought, “Here we go again.” It’s very easy for those who are out on the street to be perceived as rioters and looters.

What I noticed after about day three is that marchers basically said, “How do you persuade people? How do you convert people? We do it by simply not falling into the stereotype. We can be mad as hell, but in our space we police ourselves.” And that message spread.

There’s been a lot of recent scholarship about who gets to be the face of a movement. George Floyd ended up being that face. The first few days after his death, I saw the same pattern as with Brown. People saying, “He had this. He had done this crime.” But that shifted. There was a sense of asking, “Even if he had a fake $20 bill—which he did, he never disputed that—should he die for that?”

I think that is what allowed tiny towns in New Hampshire and Idaho to say, “You shouldn’t have to die for a misdemeanor charge.” That’s the shift I saw: Communities where this might not be a thing—they haven’t had police violence or they don’t have a lot of people of color—were able to say, “This is not a nice thing, and we are going to say ‘Black lives matter’ even though no Black people live here.” That is a cool thing.

This article also appears in the June 2021 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 86, No. 6, pages 16-20). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

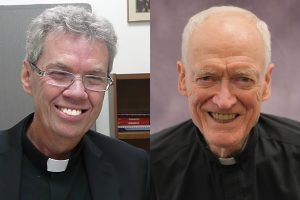

Image: Courtesy of Stacy Davis

Add comment