From 2015–2020, 136 people were executed by state or federal government in the United States. Even if judgments of their guilt were correct, is death an acceptable punishment? The Catholic Church today says no, because their lives were sacred and worthy of a chance for repentance and reconciliation.

Much like the development of other doctrine concerning issues of freedom and life—teachings on slavery and war, for example—the emergence of the Catholic Church’s opposition to the death penalty developed in recent centuries. Generally, before the conversion of the emperor Constantine, Christians were known (and often rebuked) for refusing to participate in the taking of human life for any reason.

Some Christian leaders, such as Lactantius and Pope Nicholas I, opposed use of the death penalty, while others, such as St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas, allowed it when the security of the larger community was at stake. Augustine argued against the widespread use of the death penalty but justified it in cases where the lives of innocent people in the community were at stake. Aquinas justified the death penalty when no other means could protect the common good. Similar theological arguments for the death penalty are found in the writings of Duns Scotus, St. Robert Bellarmine, St. Thomas More, and Francisco Suarez.

For centuries, when the church itself acted as the civil authority, as for example in the Papal States, it employed its own executioners. A notorious example is the Vatican’s chief executioner, Giovanni Battista Bugatti, who recorded more than 500 executions in decades of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, often gruesomely performed on the Ponte Sant’Angelo, the bridge over the Tiber River, just outside the Vatican walls.

How is it, then, that in little more than one hundred years the church shifted from directing executions on the Ponte Sant’Angelo to opposing capital punishment in all cases?

Throughout the 20th century the church took increasing exception to the use of the death penalty, in part due to the monstrous evil of the incalculable number of executions by totalitarian and authoritarian states. St. Pope John XXIII and St. Pope Paul VI were intimately witness to these state executions and to those who shockingly cited theology to claim that those executed were dangers to the community.

How is it, then, that in little more than one hundred years the church shifted from directing executions on the Ponte Sant’Angelo to opposing capital punishment in all cases?

Encyclicals like Pacem in Terris (Peace on Earth, 1963) and Humane Vitae (Of Human Life, 1968) as well as documents from the Second Vatican Council, such as Gaudium et Spes (Joy and Hope, 1965), elevated a new appreciation of the infinite dignity of the human person vis-à-vis the authority of the state. In the wake of Vatican II, Paul VI quietly removed any allowance for the death penalty from the Holy See’s own code of laws and the Vatican spoke out prophetically against executions in Francisco Franco’s Spain and Nikita Kruschev’s Soviet Union.

It was, however, during the papacy of St. Pope John Paul II that the specifics of the church’s opposition to the death penalty crystallized. As a young man in Poland, John Paul II was witness to both Nazi and Soviet totalitarianism and to their respective widespread executions. His personalist theology, formed against the horror of those executions, celebrated both the infinite dignity of each person and the infinite opportunities for salvation that divine grace provides each person, regardless of sin.

These two elements of John Paul II’s personalist theology came together in his important 1995 encyclical, Evangelium Gaudium (The Gospel of Life), to form the church’s theological argument against the death penalty. There John Paul II maintained that the modern state has sufficient means to protect the community, short of capital punishment.

Four years later, in 1999, while celebrating Mass in St. Louis, John Paul II publicly demanded an end to the death penalty. Pope Benedict XVI, following his many personal appeals opposing death sentences around the world, extended the arguments of his predecessor, in his 2011 apostolic exhortation Africae Munus (Africa’s Commitment) calling on world leaders “to make every effort to end the death penalty and to reform the penal system in a way that ensures respect for prisoners’ human dignity.”

John Paul II’s personalist theology celebrated both the infinite dignity of each person and the infinite opportunities for salvation that divine grace provides each person, regardless of sin.

Advertisement

In the summer of 2018, the Catholic office for all matters of doctrine, the Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith, took steps officially to forbid support for the death penalty by faithful Catholics, adding a new directive to the Catechism of the Catholic Church: “the Church teaches, in light of the gospel, that ‘the death penalty is inadmissible because it is an attack on the inviolability and the dignity of the person.’”

Pope Francis in October 2020, in his landmark encyclical Fratelli Tutti (On Fraternity and Social Friendship), went further to insist that the church cannot allow “stepping back” from this doctrinal injunction against capital punishment, insisting that “the church is firmly committed to calling for its abolition worldwide.”

With change in the Catechism in 2018 and Pope Francis’s binding teachings in Fratelli Tutti in 2020, the faithful are today morally obliged to oppose the death penalty, may not promote or support executions, and may not in good conscience endorse laws that allow capital punishment.

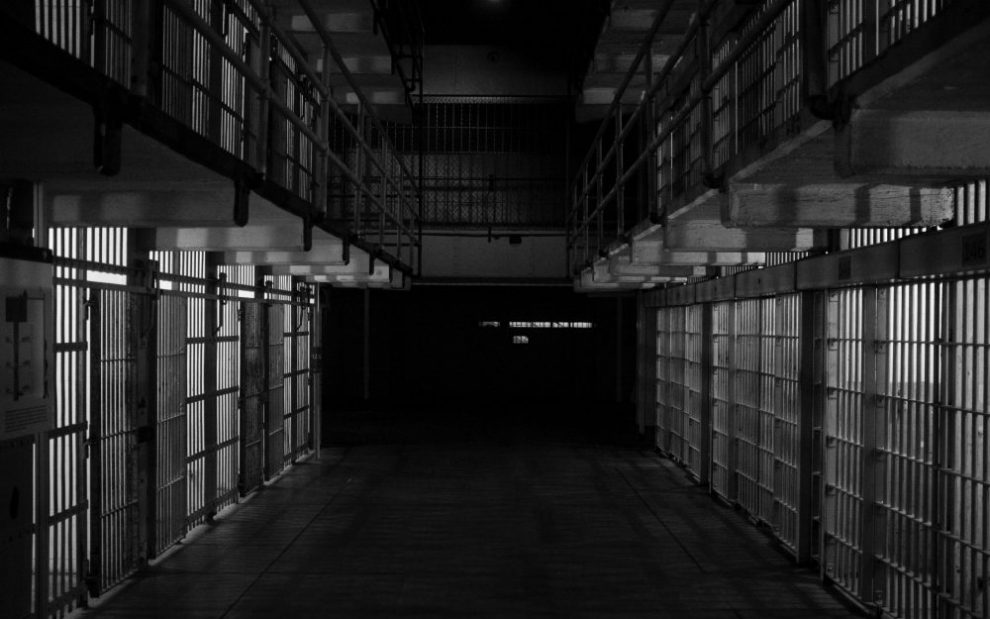

Image: Unsplash/Emiliano Bar

This article is also available in Spanish.

Add comment