There’s no such thing as bad music, says Daniel K. L. Chua, a professor of music at the University of Hong Kong. “I can get great joy from hearing my kids play in their school band,” he says. “That music isn’t played perfectly, but there is still a great joy there, however painful it may be.”

That’s because, in some fundamental way, music is joy, Chua believes. It goes far beyond a middle school student learning to play the flute or an opera singer performing an aria. “Music exists whether or not humans exist,” he says. “There’s a kind of rhythm of creation, and we tap into that.”

Music, at its most basic, is anything that repeats in some way. This could be the dripping of water against a rock, birdsong, or even the buzzing of a mosquito. Music is everywhere, throughout all of creation.

The cosmic nature of music was well understood in ancient times, Chua says, both by Eastern and Western philosophers. But as our understanding of science changed, we lost this sense of music as imbuing all of creation. For Chua, reclaiming this understanding teaches us something profound about our relationship to God and to creation that goes far beyond “good” and “bad” music.

How did ancient thinkers make sense of the world through music?

Since ancient times, music has always been associated with moral well-being. If you read ancient Chinese texts such as Confucius’, music is a cosmic joy. In ancient Greek philosophy such as Pythagoras’, music is a harmony of the spheres that brings order to the universe and to the way we live on this planet. If you read theologians such as Clement of Alexandria or Augustine, music is the cosmic embodiment of joy. It is something that gives us access to God’s divine joy.

Music continues to have the same capacities we associate with joy and order. We might not talk about the harmonic order of the universe anymore, but there is still a rhythmic order. In other words, there’s an order that helps structure our experience of time. Why is time coherent? Why is it meaningful? I think music speaks to that.

God made music as a way of understanding creation. Therefore, music brings us closer to God.

With music, we can share time with one another. We can be in time, as it were, with the universe. Music does this simply by repeating in endlessly variable ways. That, to me, is the beginning of a structure of joy. It just keeps going. Whatever the circumstances, music just won’t stop. It’s like hope in that it doesn’t give up.

The joy of music is in its very generous and generative ability to make sense of time. It actually discloses something about time, if you think about it. Time is not something you can really know. You’re just kind of in it. But music has a special way of articulating time in a meaningful way. Music is this amazing gift that allows us to be in time, as it were, with the world in which we live.

Music is always generative; it always wants to give more. It is very elastic, very giving, very capacious. The question for me is: How do we recover that sense of joy in music today? As science has advanced, we have lost that cosmology, that sense of music as ordering the universe.

What do you mean by joy?

Joy is a complex emotion—maybe not even an emotion, maybe it’s more a state of being. The key thing about joy is that it’s not really happiness. You can be joyful even when circumstances are dreadful. You don’t need to be happy to have joy. So joy is both an emotion and something you’re able to stand on or fix your eyes on. It involves hope, love, peace—all these are a part of joy. It’s a sort of moral category.

Take, for example, the story of when the woman, sometimes thought to be Mary Magdalene, anoints Jesus with oil in Mark, Chapter 14. The Bible says that a “woman came with an alabaster jar of very costly ointment of nard, and she broke open the jar . . . and poured the ointment on his head” (Mark 14:3).

This is an act of devotion and worship and is actually a kind of lament—you probably wouldn’t call it joyful. It’s also a ridiculous waste of money. In fact, people point out that the money could have been given to the poor instead. But joy is like that: It’s always about something that is more than enough. There’s this kind of generative and generous element to joy. It’s what comes out of that expensive perfume bottle: Once it comes out, you can’t contain it. It just fills the whole room as this kind of fragrance that speaks to the future. So even though Mary anointing Jesus is an act of lament, it’s also in another sense a prophetic act that looks forward to joy.

The gospels speak of Mary Magdalene having a sort of “trembling joy” at the resurrection. This too, I think, is tied to lament—the initial, very costly lament she felt after the crucifixion. So here, too, even lament is fundamentally joyful because it is excessive. It speaks to the future.

Music is fantastic at expressing sadness, at lamenting. A lot of people, when they start theorizing about music from a more tragic worldview, want to see music as fundamentally tragic. But I would flip that and say, like the story of Mary, music is so amazing at expressing the tragic because it is fundamentally joy.

Music is a call toward relationship, toward a new understanding of what it means to be in the world and to be with one another.

Advertisement

If music were truly an art form of despair, it wouldn’t make any sense. It wouldn’t fit together. It wouldn’t make you feel something beautiful in the midst of lament.

There’s actually a contradiction between the structure of music, which is coherent and joyful and never gives up, and the content, which can be one of intense sadness. Music is able to hold these two things together and produce something amazing and expressive. That, to me, is not fundamentally tragic: It’s fundamentally joyful and hopeful. Music won’t let you totally despair. It’s not possible in music.

St. Augustine writes that God is music. What does that mean?

Fundamentally, it means that God created a universe that is music. God isn’t the music in the universe, but God made music as a way of understanding creation. Therefore, music brings us closer to God. We can find a certain joy in knowing God through music and a joyful rest in God if we understand ourselves as part of that symphony of praise.

On the one hand, there’s a sense in which Augustine is trying to access God through this very abstract notion of eternal music. He understands God as someone who creates a beautiful harmonic order of time. He does all this work thinking about music as numbers—as metrical proportion—and projects this numerical order into this cosmology.

On the other hand, Augustine also writes about music as an expression of joy that has nothing to do with abstract calculations. It’s just something we do as humans. We just love being effusive with rhythmic patterns when we’re joyful. And this act touches the very heart of who God is and why God created the universe the way it is.

Augustine writes about workers in the field. He says they have to “swing” to a rhythm to do their work—“it don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing,” right? So they’re sort of swinging, and then they begin singing a song looking forward to the harvest to come, and suddenly they’re so joyful they break into improvised singing and shouting. Augustine says that this is an analogy for what happens in the psalms when they say “shout to God” (Ps. 47) or “sing to the Lord a new song” (Ps. 96)—it’s the same kind of singing.

Did other early Christians have a similar sense of the importance of music in understanding God?

Clement of Alexandria talks about Jesus as the musical Logos. He takes the “science” of his day, which was this kind of musical cosmology, and makes it into a theology. Basically, he says in the beginning was the Word and that Word is a song.

Imagine the world as cosmic harmony. While Pythagoras would say that the harmony of the world is perfect, Clement says the harmony is broken because of sin. But Christ has a new melody—he retunes the world and creates this symphony where he is one with us, with our music.

Humans join in with a music that is already happening.

So Christ is with humans, and the rest of creation harmonizes with Christ to the glory of God the Father by the power of the Holy Spirit.

Clement had this very trinitarian understanding of Christ as a new song that recalibrates the universe. And we just celebrate with this new song. So, in a way, salvation and redemption are about music. It’s very joyful in that sense.

I just love this image. It helps us to understand that Christ as the Logos is with us when we worship God the Father. It’s almost as if Christ is the worship leader. He’s the one who leads us in praise and brings us into Augustine’s symphony of praise.

If Christ is the musical Logos, what does it mean to say that “all creation sings”?

I have a very broad definition of music. I would say that anything that repeats and that draws your attention to that repetition is music. If you were in an underground cave system and there’s water dripping from the ceiling into an underground lake—that’s music. Music does not need humans to exist. Music has always existed. There’s a rhythm of life in creation, and humans tap into that.

I like to imagine that other species also enjoy music, but it’s obviously on a different scale. If you were a tiny fruit fly, for example, with a different metabolic rate, you’d hear music or repetition in a completely different way.

This means that we humans join in with a music that is already happening. The angels were already praising God, right? It’s important to get away from a human-centered approach to worship, as if we’re the only creatures that really matter or that we’re somehow exceptional from the rest of creation. No, we’re just part of creation—a very important part—and we’re part of redemption and have a special song to sing.

Why do you think we lost that ancient understanding of music as ordering the world in some profound way?

Personally, I blame it on opera. Basically, around the birth of opera in about 1600 you can see a change in how people conceive of music. Instead of being this heavenly cosmology, music is about my song or our song—it has power or influence over other humans. It becomes very, very human. Humans become the most important articulation of music. So music moves out of the sciences and into the rhetorical arts—it becomes basically about the manipulation of human feelings. I think that’s one reason why we lost a bigger vision of music in the theology of creation.

Does music still have something to say about the universe?

To many ancient thinkers—Pythagoras, Confucius, Augustine, and Clement of Alexandria—the world was ordered harmonically. It was a beautiful, eternal proportional order. But modern science understands the world very differently. Instead of harmony, we understand the world more in terms of rhythm or time.

Like music, the universe is fundamentally about repetition; that’s how it works and it’s how time works. So yes, music is still part of that fabric of space and time. We can begin to understand music in a cosmic way in this sense. If music helps us understand time, then in some sense it helps us understand how the universe makes sense for us as humans.

In 1977 NASA, in its wisdom, decided to send a Golden Record full of music into space on the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft. It’s still going out into space. It’s the farthest human-made object from our planet right now.

There is a belief, even among scientists, that music fundamentally speaks to the universe.

Why did they do this? Carl Sagan talks about a belief, deep down, that music is a universal language. There’s something about music that can communicate with an alien life form. Maybe it’s so alien it’s not even made of carbon—I don’t know, right? But somehow, music can still speak even if our languages would never make any sense to this alien.

The Golden Record also contains various messages in different languages, but somehow the scientists thought, “Well, if these don’t work, then music might do the trick.” Music’s repetitive and mathematical properties will still make sense somehow. There is a belief, even among scientists, that music fundamentally speaks to the universe or is a part of the fabric of the universe.

So, in other words, music is calling us to understand our role in creation in a new way.

I think that music is a call toward relationship, toward a new understanding of what it means to be in the world and to be with one another.

Humans have an ability called entrainment that enables us to share rhythms together. We can’t help but tap our feet to rhythm. It brings us together. We can actually share the same time together, which is amazing. Music is about helping us come into relation with the world, with one another, and with creation. If you’re a theologian, then it offers a doxological relationship with God—which is what Clement of Alexandria so beautifully described.

I don’t think music is instrumental in converting people or anything like that, but it is instrumental in expressing relationship and the joy of relationship. Even when it’s a lament. Even if you’re mourning the state of the world through music, there’s a fundamental joy that speaks of hope and a faithfulness to God’s providential care. Music always points to that in some way: It always tells you not to give up.

One of the most amazing composers of the 20th century was a Catholic named Olivier Messiaen. For him music is fundamentally joy and goes far beyond humanity. He talks about birdsong as a source of music. There is a huge Christian tradition that understands music as joyful in this cosmic creaturely sense. We need to celebrate that and rediscover it in our worship.

I think the easiest way to understand how music is joy is just to listen to the amount of repetition there is. If music were language—which it isn’t—it would sound really, really silly. When you set words to music, often you repeat these words almost infinitely, but it still makes sense, even though it wouldn’t if it were just talking.

If you begin to understand music as fundamentally the repetition of rhythms, then you begin to see how music is this generative force that creates new things with each repetition. It’s not that it just repeats the same thing all the time—that would be very boring—but it repeats itself continually in new ways.

Augustine loved music so much that he thought he was in danger of making it an idol. Yet he points out that music as repetition says so much more than what words can say in worship. Music enhances communication beyond words. It’s like when you are so joyful you run out of words and just have to repeat things endlessly. It’s like scat singing in jazz or improvising while taking a shower. For Augustine joyful repetition is at the heart of worship.

That, to me, is a fundamental articulation of joy. We never give up hope. That’s what music promises.

This article also appears in the April 2021 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 86, No. 4, pages 16-19). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

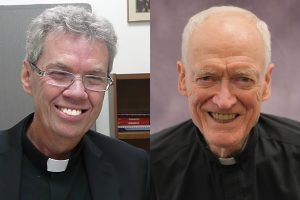

Image: Courtesy of Daniel K.L. Chua

Add comment