“Mommy, what’s this book about?”

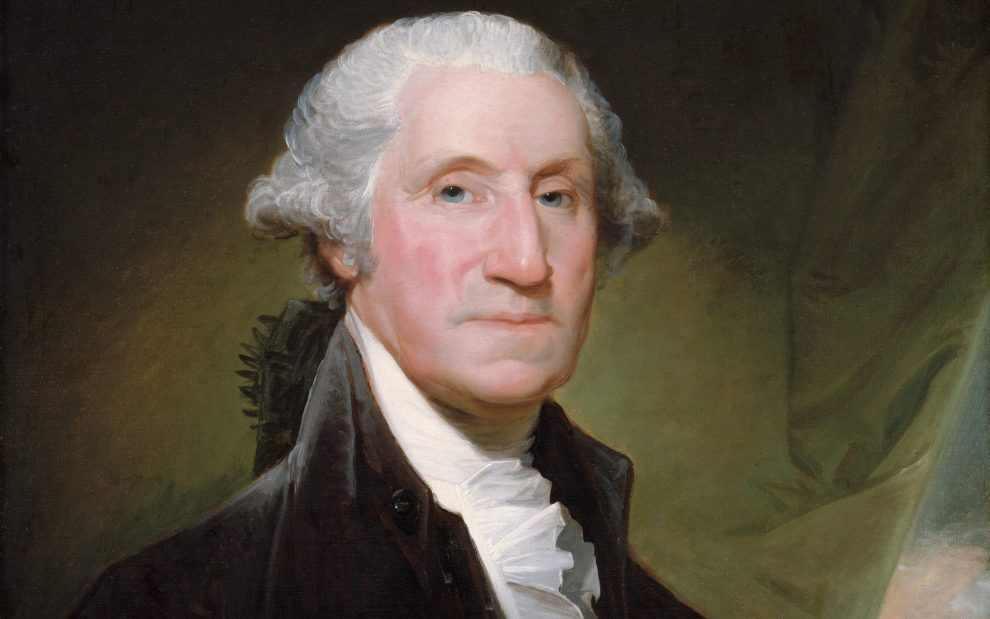

My 7-year-old daughter held up a book from our library stacks in the corner, curiosity enlivening her blue eyes. The work in question was one of the picture books I have been collecting to infuse my children’s American history curriculum with minority perspectives. It was about Ona Judge, a young woman who escaped enslavement by George and Martha Washington. I told my daughter as much.

“Wait,” she said slowly. “George Washington . . . like, the president?” Her eyes flashed as she put the pieces together. Finally, she exclaimed, “He was a bad man?!”

I’ll admit I was slightly taken aback—and grateful my father was not in the room to hear the quintessential American hero thus derided by his granddaughter! But the question led to discussion, and although I had to backtrack numerous times—“most people back then thought slavery was OK” is insufficient when what I mean to say is “most white people back then didn’t want to admit slavery was wrong because it would cost them a lot of money and a way of life”—we began to work through the nuances and contradictions inherent in human activity.

I am inspired by the leaders in the growing movement to counter false narratives in education, including organizations such as Reclaiming Native Truth, the UNCF (United Negro College Fund), the National Urban League, and Education Post, as well as many women religious, who often have been pioneers in the work for justice through education. These efforts, however, put us on the receiving end of President Trump’s ire in September when he proclaimed that teaching American history in a way that abides critical race theory is “a form of child abuse in the truest sense of those words.”

Instead, Trump said, American history should be taught so as “to defend the legacy of America’s founding, the virtue of America’s heroes, and the nobility of the American character. . . . We want our sons and daughters to know that they are the citizens of the most exceptional nation in the history of the world.”

Though I love this nation, I reject the notion that fostering patriotism should entail an avoidance of reckoning with the experiences of those for whom America has not been “exceptional.”

I am sympathetic to President Trump’s claim that “America’s founding set in motion the unstoppable chain of events that abolished slavery, secured civil rights, defeated communism and fascism, and built the most fair, equal, and prosperous nation in human history” (though I would urge a redefinition of prosperous). However, this chain of events was not “unstoppable” but the result of centuries of struggle, setbacks, and small victories. And there is still such a long way to go.

Although our nation may have been, as Abraham Lincoln said in the Gettysburg Address, “conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all are men created equal,” many have been excluded from this ideal.

Though I love this nation, I reject the notion that fostering patriotism should entail an avoidance of reckoning with the experiences of those for whom America has not been “exceptional.”

Lincoln himself was a white supremacist. In an 1858 debate against Stephen Douglas for the Illinois Senate race, he explicitly claimed to be “in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race,” and opposed to “bringing about in any way the . . . equality of the white and black races.”

Condemning specifically Black people’s participation in voting and serving on juries or in public office as well as interracial marriage, Lincoln posited that differences between the races prevent their social and political equality. However, he maintained, “I do not perceive that because the white man is to have the superior position the negro should be denied everything.” To wit, Black people should be free—whatever that can mean for “inferior negroes” prevented from participating in self-governance.

I want my children to learn that heroes and villains are often more complex than we acknowledge. George Washington the slave owner and Abraham Lincoln the white supremacist were products of their time and should not be unambiguously condemned for their limited moral vision. In many other ways, they were heroic and should be honored and emulated accordingly.

However, if we do not learn to process the aspects of their worldviews that perpetuated the myth of white supremacy, we are in danger of limiting our own moral vision and that of our children as well.

If our national heroes have held racist worldviews, it stands to reason that these have been reflected in the ethos of our country. Our social structures have been built to the advantage of white people and to the detriment of people of color. Discrimination still persists in voting, income, health care, education, criminal justice, housing, and across every other socioeconomic measure. The impact of centuries of enslavement and discrimination is still reverberating in Black and indigenous communities. Violence is a symptom of this.

I want my children to learn that heroes and villains are often more complex than we acknowledge.

Advertisement

Our worldviews are informed by our education and experience, and education and experience are shaped largely by the worldviews of those creating policy: It is a mutually constitutive relationship. Without providing a contextual framework through which to appreciate the moral complexity of human existence, this cycle preserves a whitewashed view of history that precludes the possibility of seeing and addressing critical systemic issues.

Sarah Sunshine Manning, NDN Collective Director of Communications and citizen of the Shoshone-Paiute Tribes of the Duck Valley Indian Reservation in Idaho and Nevada, and Chippewa-Cree of Rocky Boy, Montana, puts the question pointedly:

How can policy makers respond to the epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women, to police brutality against Native Americans, to youth suicide in tribal communities, to poor mental health, to negative outcomes in education for Native youth, to fights for tribal sovereignty and fights against environmental racism, when Indigenous People are not even on their radar? When the unchecked negative portrayals of Native Americans continue to increase the level of discrimination against tribal communities while reinforcing institutional racism in spaces where modern Native Americans are known of, how can America ever call itself a country that is just?

St. Augustine recognized long ago that civic heroes are necessary, even though they are flawed. In City of God, Augustine positions his account of public virtue and civic leadership against Cicero’s “ideal statesman,” who is meant to exemplify perfect justice through his own human effort.

Augustine argues that such a perfectionist cannot function as a just and compassionate ruler—for certainly no human being has ever been perfectly just, and so any claim to the contrary is a symptom of pride and distorted moral vision. Rather, justice and compassion depend upon the sense of shared identity that comes from humanity’s shared sinfulness and capacity for virtue.

For Catholics, who are called to look at the world through the lens of salvation history, it should be clear that a worldview dismissive of sin is invalid and unhelpful. Rather, the history of the world is one of human beings falling from grace—and of the grace of God redeeming human beings when we acknowledge our sinfulness and dependencyand work to restore right relations with one another and our world.

Why should American history be exempt from this narrative?

Our nation was founded in the pursuit of liberty and justice, and we may celebrate the ways this has facilitated flourishing for many around the globe. But still we may fault the limits our founders placed on these concepts and recognize the ongoing, pervasive tension between ideals and practice, both nationally and abroad.

As the primary educator of my children, one of my responsibilities is to equip them to view history with a critical lens that can help illuminate just responses to contemporary issues.

The Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church says that “the family has the responsibility to provide an integral education. . . . This integrality is ensured when children—with the witness of life and in words—are educated in dialogue, encounter, sociality, legality, solidarity and peace, through the cultivation of the fundamental virtues of justice and charity.”

By emphasizing minority perspectives and experiences, I can broaden my children’s perspective and teach them, as Pope Francis writes in Fratelli Tutti (On Fraternity and Social Friendship), to find “ways to include those on the peripheries of life. For they have another way of looking at things; they see aspects of reality that are invisible to the centres of power where weighty decisions are made.”

As the primary educator of my children, one of my responsibilities is to equip them to view history with a critical lens that can help illuminate just responses to contemporary issues.

Liberty and justice are not static ideals: Each generation must continue to make progress, through grace, toward their authentic realization. In this effort, as stated in “Justice in the World,” the 1971 World Synod of Catholic Bishops document: “[The] power of the Spirit . . . is continuously at work” as we cooperate “with God to bring about liberation from every sin and to build a world which will reach the fullness of creation only when it becomes the work of people for people.”

Integral, antiracist educational models will be critical in shaping this vision—for, as Sarah Sunshine Manning writes, “It isn’t just a time of narrative change. It is a time of truth.”

This article also appears in the February 2021 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 86, No. 2, page 27-31). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Wikimedia Commons/ Gilbert Stuart, “Portrait of George Washington”

Add comment