Read

Missionaries

By Phil Klay (Penguin Press, 2020)

Before turning to full-time writing, Phil Klay put in more than a year’s service with the U.S. Marine Corps in Iraq. His experience there contributed to his debut work in 2014, Redeployment (Penguin Press), a collection of short stories outlining the conflicting emotions of comrades in arms. With Missionaries, Klay has completed two works of fiction examining in part the believer’s response to the hard realities of peacekeeping.

Klay’s latest effort builds again on his wartime experience to present a message about the international, globally connected components involved in waging even localized wars. Missionaries offers graphic insights into military adventure, whether in conventional deployment as in Afghanistan or in situations in which U.S. advisers interact with national armies and mercenaries, as in the Colombian government’s long-standing conflict with local militias, insurgents, and drug cartels.

The novel’s title is intriguing. Readers typically think of missionary work as an effort to evangelize a religious truth. But for Klay, the sense of mission takes on a more ominous connotation. As Juan Pablo, a colonel in the Colombian military and later a conflicted soldier of fortune relates partway through the novel, “[T]he missions . . . did make sense. It was the war as a whole that was insane, a rational insanity that dissected the problem in a thousand different ways.”

Despite some difficulty following the narrative with its shifting points of view, Missionaries succeeds in conveying the excessive suffering, nihilism, hopelessness, and flimsy rationalizations visited upon war’s practitioners, supporters, and victims.

The characters pose questions about the solace that faith might provide amid seemingly endless violence, suffering, and death. Ultimately, for the novel’s key players, faith exists not to guide one’s behavior but to trouble the conscience and seek justification when horrible things are done.

—Mike Mastromatteo

Strange Rites

By Tara Isabella Burton (PublicAffairs, 2020)

In an era when religious questions can be contentious and divisive, Tara Isabella Burton’s Strange Rites: New Religions for a Godless World opens with an episode of unlikely agreement between evangelical leader Jerry Falwell and atheist author Sam Harris. In the early 2000s both men stated in high-profile interviews that America was becoming increasingly godless. The agreement ended there: Whereas Falwell foretold of terrorist attacks and natural disasters as the consequences for Americans’ casting God aside, Harris foresaw a brighter, more humane nation as Americans gave up their harmful fairy tales.

Fifteen years on, the fact that neither man’s vision has come to pass suggests weaknesses in their analyses. Although faith in mainstream religious institutions has crumbled and these organizations have seen precipitous declines in membership, Burton forcefully argues that religion in America is not gone. Instead, it is being remixed—and in the process, revitalized.

The religiously remixed are as various as “Chreaster Catholics” smudging sage to cleanse their homes and preparing dishes for a friend’s vegan Shabbat to fan communities for Mormon “mommy blogs.” Calling these groups religious may elicit eye rolls from more traditional-minded readers, but Burton shows how remixed flocks provide the same “meaning, purpose, community, and ritual” that traditional institutions purport to offer.

The book’s strength lies in the way Burton interweaves anecdotes about fans’ exegetical readings of the Harry Potter series or implicit theology of SoulCycle with academic research. Interesting, if not innovative. Christianity, the religion that most of the religiously remixed are reimagining or leaving behind entirely, is a mash-up of Jewish messianism and Platonic philosophy with practices from Roman state religion and the ancient Celts. “Remixed religion” isn’t new: For the phenomenon Burton describes, religion works fine.

Nicholas Black Elk: Medicine Man, Catechist, Saint

By Jon M. Sweeney (Liturgical Press, 2020)

The latest title in Liturgical Press’ People of God series, this biography of Oglala Lakota medicine man and Servant of God Black Elk looks at his complex cultural and spiritual identity.

The Greatest Beer Run Ever

By John “Chick” Donahue and J. T. Molloy (William Morrow, 2020)

More than a war memoir, Marine veteran Donohue’s humorous and poignant tale of delivering beer to the troops during the Vietnam War is a testimony to the bonds of friendship.

I’d Do It All Over Again and I’d Do It Better

By Janaan Manternach (ACTA Publication, 2020)

Catechetical education writer Manternach shares the struggles and insights of being a caregiver after her husband and coauthor, Carl Pfeifer, developed Alzheimer’s disease.

Listen

Good Luck With Whatever

Dawes (Rounder Records, 2020)

For at least a decade now, the term dad-rock has been thrown around as a hipster insult for the kind of music Gen X fathers inflict on kids locked in the minivan. But Dawes, a band of Los Angeles Millennials, has been making dad-rock since their early 20s.

Dawes’ particular niche in rock has always been the early 1970s folk-rock sound that ran from Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young to the Eagles. So genre-wise Good Luck with Whatever is no surprise. It’s got crunchy Crazy Horse guitar, Warren Zevon piano, and some Jackson Browne introspection. But the strongest influence is the world-weary wisdom of Don Henley’s post-Eagles solo work—think “The End of the Innocence” and “The Heart of the Matter.”

Dawes’ singer and songwriter, Taylor Goldsmith, is now 34, married, and about to have his first child. Those landmarks inevitably bring a consciousness of passing time, life’s promises and limits, choices made or postponed, and their consequences. Hence the ambivalent tone that pervades most of the album’s songs from the opener, “Still Feel Like a Kid,” in which the singer confesses to sore muscles and earlier bedtimes but stubbornly insists on the title refrain, to the closing, “Me Especially,” in which he wonders, “Why am I still the youngest guy my age?”

However, the album plumbs its spiritual depths on the mid-tempo, piano-driven track “Didn’t Fix Me.” The song follows the pilgrim down several paths of spiritual progress: true love, career success, mindfulness healing, even community service. None work quite like he thought they would, but he doesn’t seem ready to give up.

That’s emblematic of the open-hearted earnestness that characterizes this record. Call it dad-rock if you like, but it’s also living proof that adulthood has its advantages.

Watch

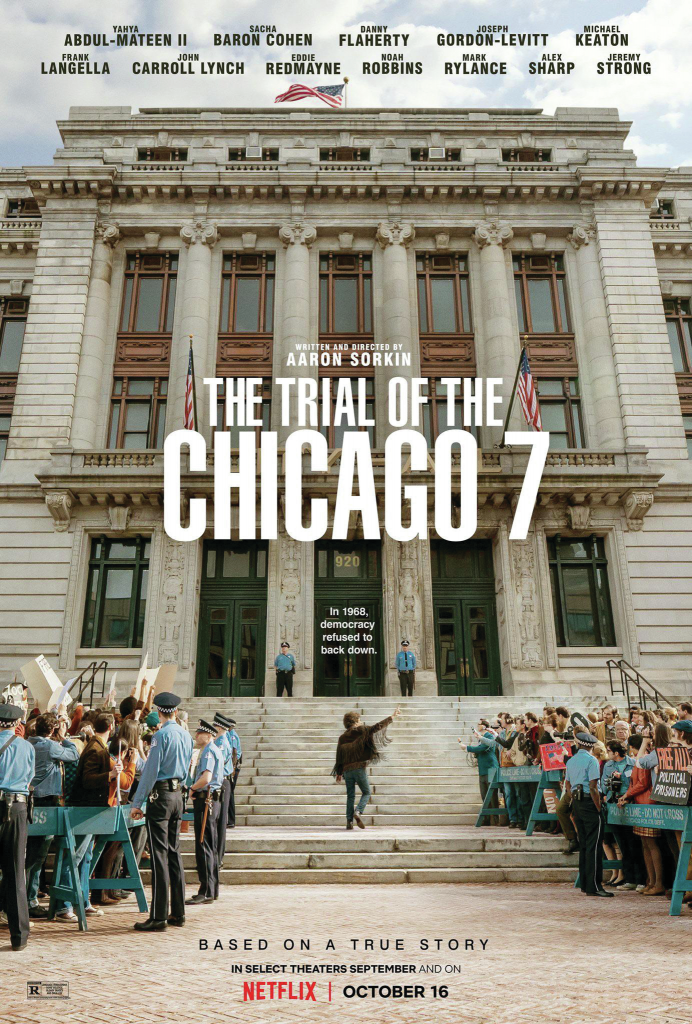

The Trial of the Chicago 7

Directed by Aaron Sorkin (Netflix, 2020)

As The Trial of the Chicago 7 nears its finale, two of the antiwar activists on trial for allegedly starting a riot at the 1968 Democratic National Convention get into a fight. “What is your problem with me?” Yippie activist Abbie Hoffman (Sacha Baron Cohen) presses Tom Hayden (Eddie Redmayne), the straitlaced leader of Students for a Democratic Society. “My problem is that for the next 50 years, when people think of progressive politics, they’re going to think of you and your idiot followers passing out daisies to soldiers and trying to levitate the Pentagon.”

Up to this point, the movie had used a fairly light hand in sketching how various factions of the antiwar movement converged on Chicago and managed their differences to protest the Vietnam War at the convention. This confrontation between Hoffman and Hayden reads as an apologia from writer-director Aaron Sorkin (A Few Good Men, The West Wing), who has made his fortune dreaming up governments run by eloquent, affable milquetoasts.

Although discordant, this scene is mercifully short and the rest of the movie avoids such homilizing. There are great performances from all the actors. Judge Julius Hoffman (Frank Langella) presides at the trial, and Langella’s performance spectacularly captures the toxic admixture of imperiousness, ignorance, and pettiness that gnaws away at defense attorney William Kunstler’s (Mark Rylance) faith in the legal system. Watching Kunstler grow increasingly frustrated while keeping his defense razor sharp makes the character deeply sympathetic.

Told through flashbacks provoked by questioning at the trial, as well as narrated in scenes by Abbie Hoffman’s stand-up comedy, the movie is fast-paced and fun despite the seriousness of its subject matter.

This article also appears in the January issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 86, No. 1, pages 38-39). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Unsplash

Add comment