The icon of the holy family that adorns the bedroom of Steve and Andrea Kaneb is different. Mary and Joseph look older than they are usually depicted, and Jesus is a man in his 20s. The image reflects the home life of the New Hampshire couple. Their adult son Philip has a developmental disability and lives at home with his parents.

This isn’t the only evidence of their family life enriching their faith. Steve, a permanent deacon of the Diocese of Manchester, credits his five kids—all of whom are now grown—with opening his eyes to a diversity of life experiences: One is gay. Two are adopted. The adopted son has darker skin and gets pulled over all the time, so Steve turns up at Black Lives Matter protests, something that perplexes other members of his diaconate cohort.

“I think the church is the perfect player in all these areas where there’s conflict. The Catholic Church in particular is bound to be present to everybody—to be attentive and listening,” Steve says. He credits Andrea, his wife of 36 years, for modeling the goodness he seeks to live out. Andrea suffers from significant hearing loss. She helps others with hearing loss get access to the resources they need and teaches them how to use them.

“This is part of living out your faith,” says Julie Hanlon Rubio, a professor of social ethics at the Jesuit School of Theology of Santa Clara University in Berkeley, California. Rubio is a leading advocate for an understanding of Catholic family life that is broader and goes deeper than checking a few boxes of devotional practices and sexual morality. Her latest book, Sex, Love, and Families: Catholic Perspectives (Liturgical Press Academic), coedited with Jason King, gathers a chorus of Catholics to weigh in on issues including hookups, gender identity, migration, and digital technology.

When couples live their marriage vocation in an outward-facing way that fosters justice and is leaven to a community, Rubio says it forms stronger families, “because they’re doing this thing that isn’t only for them.”

Pope Francis echoes Rubio’s work in his new encyclical, Fratelli Tutti (On Fraternity and Social Friendship), in which he says that life cannot be reduced to relationships with a small group of people, even one’s own family.

“Our relationships, if healthy and authentic, open us to others who expand and enrich us,” he writes. “As couples or friends, we find that our hearts expand as we step out of ourselves and embrace others. Closed groups and self-absorbed couples that define themselves in opposition to others tend to be expressions of selfishness and mere self-preservation.”

The hallmarks of this outwardness include works of mercy, radical hospitality, an openness to surprising calls from God, and, ultimately, a wider picture of how fruitfulness—part of the Catholic marriage vocation—is lived out in practice.

Wide mercy

Rubio views the 2014–2015 Synods of Bishops on the Family as an effort by Pope Francis to make sure that families see themselves as part of his program of going out to the peripheries.

“All of that was to bring everybody in, to make the church feel more like a home—an open home where it is not about judgment but about mercy,” she says.

Aimee Murphy, 32, of Pittsburgh formed a foundational bond with her future husband through an experience of mercy. She and Kyle, 35, met in college, and the Catholic nature of her social circles meant that she wasn’t comfortable sharing with anyone that she’s LGBTQ.

But not long after she and Kyle started dating, she admitted that she shared his attraction to a woman in a movie they’d just gone to see and found herself “ugly crying in the car” as she came out to him.

His response, she recalls, “It was just, ‘I love you,’ ”—the first time he ever told her.

In living out her marriage, Aimee draws from a section called “An Expanding Fruitfulness” in Amoris Laetitia (The Joy of Love), the letter from Pope Francis that was the fruit of the family life synods. She says, “It talks about how couples are called to live justice and mercy and serve the poor and all these different little things that I had felt were so glossed over.”

An ardent pro-life activist in college, Aimee has progressively expanded the scope of her advocacy. She started Life Matters Journal (now the organization Rehumanize International) the year she and Kyle got engaged. “By the time we got married, Kyle had an accurate picture of what he was getting into as far as my consistent life ethic activism,” she says. Her organization works against all forms of aggressive violence.

Even before being ordained a deacon, Steve Kaneb was active in lobbying against the death penalty. He sees a consistent witness as essential.

“It’s really one message—of particular attention to the vulnerable who are marginalized and, in some cases, not welcomed,” Steve says. When others challenge him and say they would only abolish the death penalty if a prohibition of abortion was also guaranteed, he scoffs. “That’s not how life works,” he says.

The prodigious outreach of the Kanebs and Murphys doesn’t surprise Bridget Burke Ravizza or Julie Donovan Massey, both of St. Norbert College in Wisconsin. Both married with families of their own, the two interviewed 50 married couples for their 2015 book, Project Holiness: Marriage as a Workshop for Everyday Saints (Liturgical Press).

“We were blown away,” Burke Ravizza says when recalling how interviewees were out in their communities “bringing more God into the world.”

However, when the two would ask couples about positive messages on marriage they’d heard from church, Massey says, people would invariably complain about the official church and shift their focus. “They talked about other families,” she says, models they saw in the pews around them.

“It’s really one message—of particular attention to the vulnerable who are marginalized and, in some cases, not welcomed,” Steve says.

Pope Francis echoed the findings of Project Holiness three years later in his apostolic exhortation on holiness, Gaudete et Exsultate (Rejoice and Be Glad), in which he writes about the saints “next door.”

Julie Hanlon Rubio affirms this development: “Holiness can’t be this otherworldly thing or not associated with families at all,” she says. The values of faith lived out in a marriage are not limited to activism; they leave a profound mark in the home as well.

Rubio points out that in Amoris Laetitia the pope talks about inviting people in. “We’ve only just begun to imagine what a home that is open and welcoming could really be,” she says.

Radicals next door

Some homes practice a form of radical hospitality. “It certainly is the case for us that our home has become the place for a number of different kinds of encounter,” says Holly Taylor Coolman, 53, a theology professor at Providence College in Rhode Island. She and her husband, Boyd, 54, who teaches at Boston College in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, adopted five children and have a wide array of birth families, former foster families, and others in their lives.

“Those connections have created other connections for us, and we’ve tried to live our family life with a . . . more permeable boundary than most nuclear families live with,” Holly says.

Holly borrows the language of the Catholic Worker movement of blurring the boundaries between who is serving and being served in the graced encounters of Christian life. “How can we do it here without necessarily founding or moving into a Catholic Worker house?” she asks. “We’re living a middle-class American life.” She concludes that one has to sort of “defect in place” in order to “bring some pretty foundational Christian ideals to that way of life.”

For Marco and Lourdes León of Tucson, Arizona, these ideals include sharing with their adopted twins their various parish ministries such as singing in the choir and serving at Mass. Marco, 47, is a high school government teacher, and Lourdes, 50, teaches fifth grade in a Catholic school. Married just over a decade, they’ve spent their marriage percolating the values of their faith into their community and home, especially with their children, a boy and a girl who are almost 12.

“It’s beautiful that these kids wouldn’t think twice to give whatever’s in their pocket to help a homeless person,” Marco says. He describes their home as a place for grandparents, aunts, and uncles to gather in friendship and enjoy a “huge spectacle of making a meal from scratch” on Sundays, a tradition that has taken a hit during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Another area where the value of hospitality plays out for the Leóns is Marco’s teaching. Students who are kicked out of their homes have temporarily come to stay.

“We’re called to action,” Marco says of the family’s decision to open their home.

The Coolmans have had half a dozen people live with them at any given time, though Holly estimates that between end-of-semester dinners with students and the family’s regular practice of feasting more than a thousand people have been in their home.

“If you want to have a Catholic family, you have to do a lot of feasting,” Holly says, tracing the enjoyment of hosting a meal with friends back to when she and Boyd were graduate students. “Beginning without a lot of money helped us be clear that money is not really the point. Abundance is not the same thing as having a lot of money.”

Seeing fruitfulness

Nor is abundance necessarily having a large family. Like so many couples, Scott and Erica Galvin, both 39, of Youngstown, Ohio can’t have kids of their own but have made their marriage a hub of community and evangelization. They’re often surrounded by kids, as Erica’s brother brings his family to Sunday Mass.

“We’ve kind of adopted, in a way, their kids,” she says.

“We like to give time,” says Scott, describing how they take trips with and devote other special activities to their nieces and nephews.

Scott is a sports photographer, and Erica works in parish ministry. The two regularly work as a sponsor couple for engaged couples preparing for marriage. Erica sees a spirit of sharing that is downright eucharistic in this work. Pope Francis writes of a path of holiness in everyday actions in Gaudete et Exsultate. For Scott and Erica, this means sharing a casual meal at home with these couples and opening up the sacrament of their marriage for others to see.

“You watch them grow and learn more about marriage,” Scott says.

“And Catholicism,” Erica adds.

The Galvins spend as much time together as they can and work well together. That quality—and their gifts for videography and digital technology—allowed them to open up the celebration of the Eucharist for their entire parish during the lock- down portion of the pandemic, just one example of how their marriage bears fruit.

Aimee Murphy of Rehumanize International, who has also lived the heartbreak of infertility with her husband, says her advocacy for the consistent life ethic is definitely an expression of love for the whole human family. She found comfort upon a closer reading of what the Bible calls on her to do. “It’s not be fruitful by multiplying,” she says.

Bridget Burke Ravizza of St. Norbert College recalls the words from one infertile couple who participated in Project Holiness: “We worked really hard not to close ourselves in.”

Just as fruitfulness takes many forms in families, discernment of God’s call in one’s life is an ongoing reality as opposed to a choice made at one particular juncture.

Julie Donovan Massey of St. Norbert College sees the fruitful witness of couples who experience infertility as reflective of how the church oversimplifies the call of generativity in marriage to mean having kids and how that particular call spans an entire relationship, well beyond traditional childbearing years.

“There’s a lot of other fruitfulness that can be called out of their lives,” Massey says.

Going out and inviting in

Just as fruitfulness takes many forms in families, discernment of God’s call in one’s life is an ongoing reality as opposed to a choice made at one particular juncture. Pope Francis describes discernment as a lifelong process in Amoris Laetitia. The calls a couple finds along the way can be surprising.

For Dannis Matteson, 34, and Thomas Cook, 40, who met as graduate students at Catholic Theological Union in Chicago, the seven years of their marriage have seen one call after another emerge in their lives. These include working in campus ministry and working with a team to reimagine Hope House, an intentional community in Chicago’s Back of the Yards neighborhood where people can live for reduced rent while they engage in ministries of solidarity with others who live there. They also collaborated to create a space for interfaith spiritual programming called EncounterPoint and served as mentors in the program Catholics on Call for anyone discerning how to be a disciple.

“It has not led to financial security, but it has led to a lot of adventure,” says Dannis. “It opens you to your neighbors and to hard realities right in your own backyard.”

Thomas now works as a jail chaplain while Dannis pursues her doctorate at Loyola University Chicago.

Fruits of this kind are evident in the lives of other couples as well. In just the past year, Boyd Taylor Coolman worked to start an intentional community where young men could discern vocation of any kind. And in Tucson, Marco León says his faith is one reason his students seek him out for life advice.

“My kids know who I am. In many ways, it has allowed me to have some very fruitful conversations,” Marco says. “I’ve been able to guide a lot of young men and women who’ve just reached out.”

His wife, Lourdes, sees the providence in all of it. “The invitations that we receive to share ourselves with others—they’re all God-planned,” she says.

Their generous hospitality means the abundance of their home finds its way to a more universal destination, open to the surprises that God might bring into their lives and the lives of their guests.

Even a marriage in which only one spouse is Catholic or particularly religious can be a home of cooperation with calls. Luana Lienhart moved to the United States with her mother from her native country, Grenada, in the 1980s. She and her husband, Brek, are both mental health professionals based in Evanston, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago.

While Luana, 41, is a cradle Catholic, Brek, 62, is spiritual but not religious. He supports Luana’s Catholic faith because of its importance to her. Their 10 years of marriage have seen Luana join the secular Franciscans and her parish’s Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults team and accept an adjunct teaching offer at DePaul University in Chicago. She too sees the providence.

“Every single term with the students that I teach, there’s been at least one that’s had some kind of mental/health social worker crisis,” she says. These include a traumatized Iraq War veteran whose best friend had recently died by suicide, a young woman who had a sexually transmitted infection from an abusive boyfriend, and a rejected gay student.

“Justice, for us, is critically important,” Brek agrees. While he asserts that Luana has the bigger heart, Luana cites her husband’s transcending his suburban upbringing to pursue his calling in mental health in a heavily Black and Latino/a part of the city where the impacts of racism and classism are fully on display.

He also took an active interest in helping select the readings for their wedding, opting for the letter to the Hebrews (13:2) with its exhortation, “Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for by doing that some have entertained angels without knowing it.”

The value resonates with others who live the call of their marriage vocation in an outward way.

“We reach out to everyone, not just our families,” says Erica Galvin. “For us, the church is our family.”

Holly Taylor Coolman sees her family’s radical hospitality as a form of stewardship, “directing resources toward that kind of concrete shared life [that] really makes for a richer life,” she says. Their generous hospitality means the abundance of their home finds its way to a more universal destination, open to the surprises that God might bring into their lives and the lives of their guests. Although this stretching of boundaries is not easy for their family, they realize how important it is for their Christian vocation not to become closed in on themselves, as Pope Francis would say.

Remaining open in this way inevitably requires vulnerability and an awareness of one’s own need for mercy, so as to better reflect compassion to others, as Pope Francis wrote in his prayer for the Jubilee of Mercy.

“Vulnerability is what it’s all about,” says Steve Kaneb, “opening ourselves up to the divine and to each other.”

This article also appears in the January issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 86, No. 1, pages 10-15). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

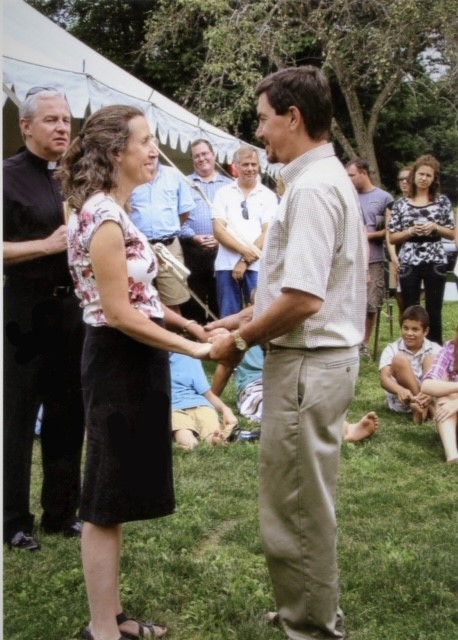

Header Image: Boyd and Holly Taylor Coolman with their family.

Add comment