This Christmas will be lonely and quiet for many of us. I wonder how those of us who love to celebrate the holidays through the gift of food and joy of cooking are going to manage. I know I won’t be baking as much as usual—but I’ll still bake and even pull out some of my cookbooks. For me, cookbooks can be an unexpected source of Christmas and community spirit.

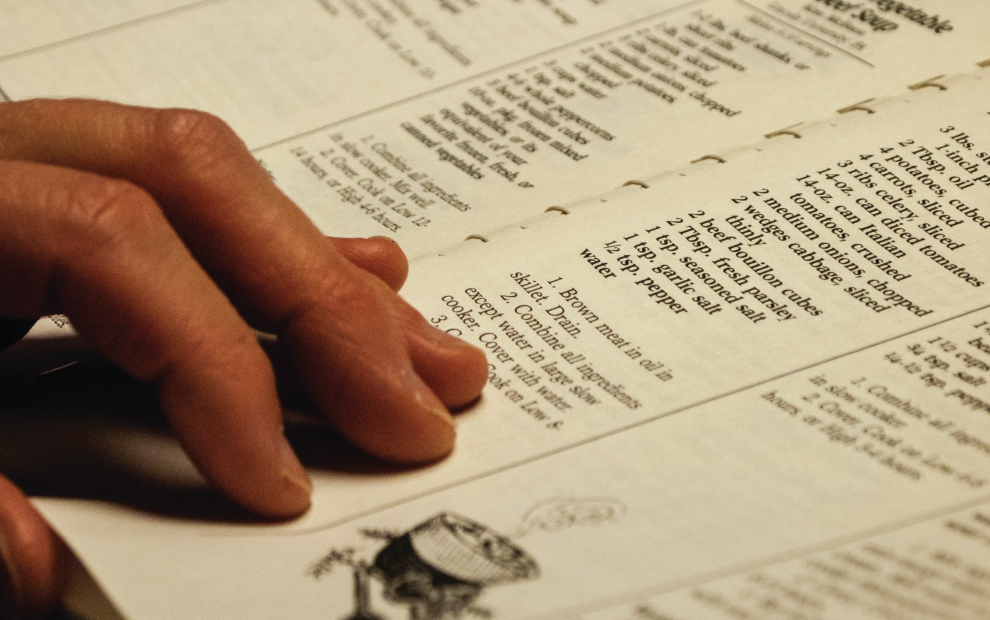

I have a bookshelf crammed with cookbooks, from the coffee table kind to Betty Crocker. The cookbooks I treasure most, however, are from my mother’s collection of church cookbooks: one from our local parish in suburban Chicago; one from my grandmother’s parish in Dubuque, Iowa; another with recipes from several rural parishes clustered around New Melleray Abbey, a Trappist monastery in Iowa; a Methodist church cookbook bought from a neighbor; and a Greek Orthodox church cookbook given to my mother by a coworker.

Most of the cookbooks were put together by the church’s women’s group or rosary committee for fundraisers. All of them hail from the 1970s and ’80s and feature the identical aesthetic of plastic comb or coil binders and laminated covers with touches of flair such as detailed parish histories, random-ish scripture and inspirational quotes, and recipes for a “happy home” thrown into the mix.

St. Raymond de Peñafort’s cookbook has original illustrations of an altar boy eyeing platters of steaming food between its sections. The cookbook from St. Anthony’s in Dubuque opens with favorite recipes from its pastors over the years, going back to an Irish stew beloved by Monsignor Peter O’Malley (“Pastor from 1898 to 1952”).

Each reveals something about its faith community. This being the Midwest, tuna casseroles abound in my mother’s collection—but in the Catholic ones the cooks gave them names like “Lenten Casserole” or “Quick Friday Casserole.” The New Melleray Abbey cookbook is chockablock with Irish and German surnames and ads for farm equipment and feed sellers, but it has a considerably limited selection of fancy appetizers. The Greek Orthodox church cookbook has a wine guide and no fewer than four recipes for pastitsio.

This being the Midwest, tuna casseroles abound in my mother’s collection—but in the Catholic ones the cooks gave them names like “Lenten Casserole” or “Quick Friday Casserole.”

I especially love the recipes with personal notes. Like the woman in my childhood parish’s cookbook who claims she “could retire comfortably” if she had a nickel for every time she was asked to make her chocolate chip oatmeal bars. Or the baker who boasts of winning a first prize of $100 with her chocolate sundae cookies recipe. Another recipe helpfully tells future parish historians that this dish “was served at the November meeting by Toni.”

These quirks are what make church cookbooks special, compared to the glossiness of professional cookbooks or the hipness and immediacy of celebrity chef blogs and recipe apps. More than just folksiness, church cookbooks offer a sense of community. Most church cookbooks don’t travel far beyond their community, so the readers know the cooks in their pages and have maybe shared a meal with them as well as a church pew on Sundays.

Trying a recipe from your parish cookbook—then telling the cook how much you or your family loved it—is another way to foster community, to break bread with someone from a distance and make a space for them at your table. It might be the best way we have to enjoy community this Christmas, with most people separated from their extended family and friends.

Quirks are what make church cookbooks special, compared to the glossiness of professional cookbooks or the hipness and immediacy of celebrity chef blogs and recipe apps.

One of the books in my collection, the New Melleray Abbey cookbook, has some recipes by my great-aunt Florence Fagan that intrigue me, including one called “Forgotten Cookies” that requires leaving the cookies in a turned-off oven overnight. Maybe as I make them I’ll think of her baking them in her farmhouse in Iowa, and I’ll invite to my table in my heart all my other absent family and friends.

This article also appears in the December issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 85, No. 12, page 7). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Pixabay/MorningbirdPhoto

Add comment