Although it has received little notice, Pope Francis introduced a new pathway to sainthood on July 11, 2017, recognizing individuals who, although not martyrs in the traditional sense, put their lives in danger out of compassion for others and died as a consequence.

“It is certain,” said the pontiff, “that their heroic offering of life, suggested and sustained by charity, expresses a true, full and exemplary imitation of Christ and, therefore, is worthy of that admiration which…the faithful usually reserve for those who have voluntarily accepted the martyrdom of blood or have exercised the Christian virtues to a heroic degree.”

The Holy Father’s new category is much needed, since it creates an avenue for those in contemporary times whose heroic witness to the gospel falls somewhere between martyrdom and an extraordinarily holy life. Without the pope’s new category, opportunities to inspire future generations would be lost as the stories of selflessly courageous individuals vanish over time.

There have been many missionaries, for instance, who voluntarily placed themselves in dangerous situations, and as a result died tragically from disease, accident, or natural disasters they would never have encountered if not for their commitment to the most vulnerable. The life and death of Carla Piette is one such story.

August 23, 1980 began as an ordinary Saturday morning for Maryknoll Sisters Carla Piette and her companion, Ita Ford. Carla set off in their jeep to deliver food to refugees from outlying areas of Chalatenango, El Salvador, torn by an undeclared, but violent, civil war, while Ita stayed behind to arrange the release of a prisoner being held by the army. This man apparently had a reputation for implicating innocent people in guerrilla activity, and when frightened refugees staying in the parish house saw the man in their midst, they told Ita they feared he was a dangerous informer.

Despite the menacing weather and approaching darkness, Carla and Ita decided for everyone’s peace of mind to drive the man to his village. Just minutes after delivering him safely, a flash flood overturned their jeep. Two seminarians accompanying them escaped, but were powerless to help in the raging waters. Trapped below by the steering wheel and drowning, Carla’s last act was to give Ita a shove that thrusted her through a narrow window.

Their lives changed dramatically as they allowed themselves to be evangelized by their poor neighbors.

The next day, Carla’s muddy and broken body was found nine miles downstream, but Ita was alive and, though grief-stricken, determined to continue their ministry to refugees. Aided by Sisters Maura Clarke and Dorothy Kazel and lay missioner Jean Donovan, these “four churchwomen,” as they came to be called, would face their own deaths three months later, at the hands of the Salvadoran National Guard.

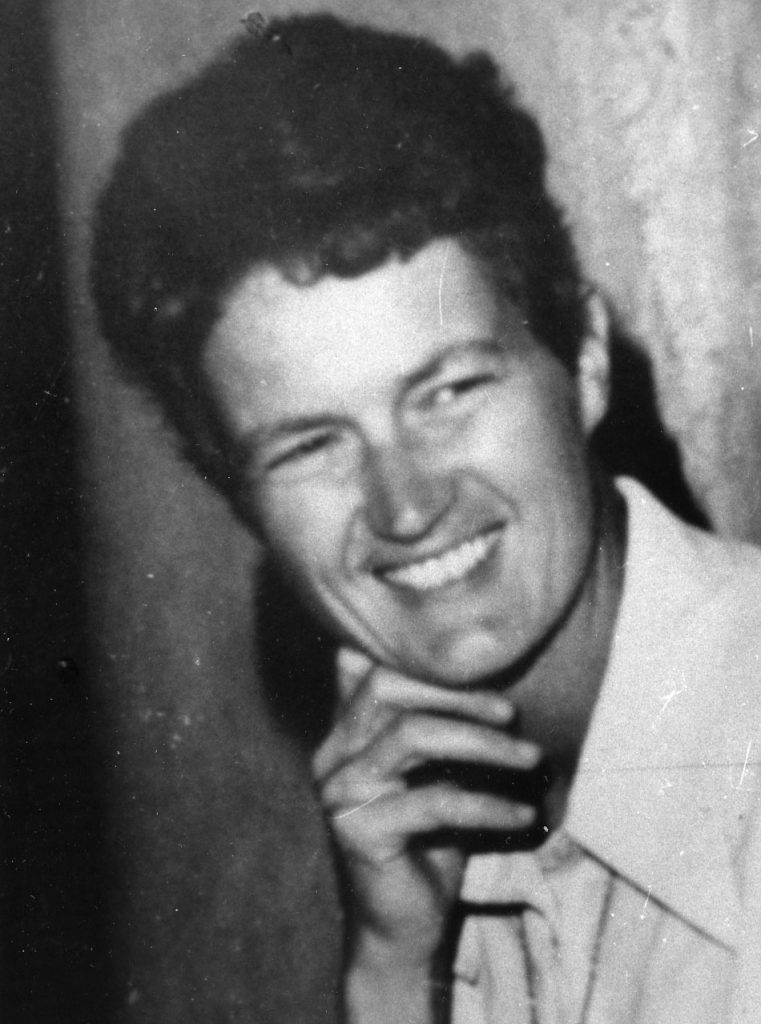

Carol Ann Piette’s journey to El Salvador began when she entered Maryknoll in 1958 from Appleton, Wisconsin. Later known as Carla, she was outspoken and impulsive, a poet who played the clown and fought depression with wit and zany humor. Assigned to Chile in 1964, Carla was a dedicated and innovative elementary schoolteacher, but after eight years she became restless. Her poem “Poverty” from this time reveals Carla’s wish to overcome her shortcomings and become one with the “poor ole beat-up people,” as she affectionately called the most needy and vulnerable:

The poorest urchin approaches

he takes one finger in his starvling clasp,

a ragged miss stands by.

She stares, not wanting to remove

his warming glance

A vested Nun withholds, respectfully,

full of poise,

NO VACANCY for need.

When will I shed

my finely woven answers

and stand before Him, dirty, bare and poor?

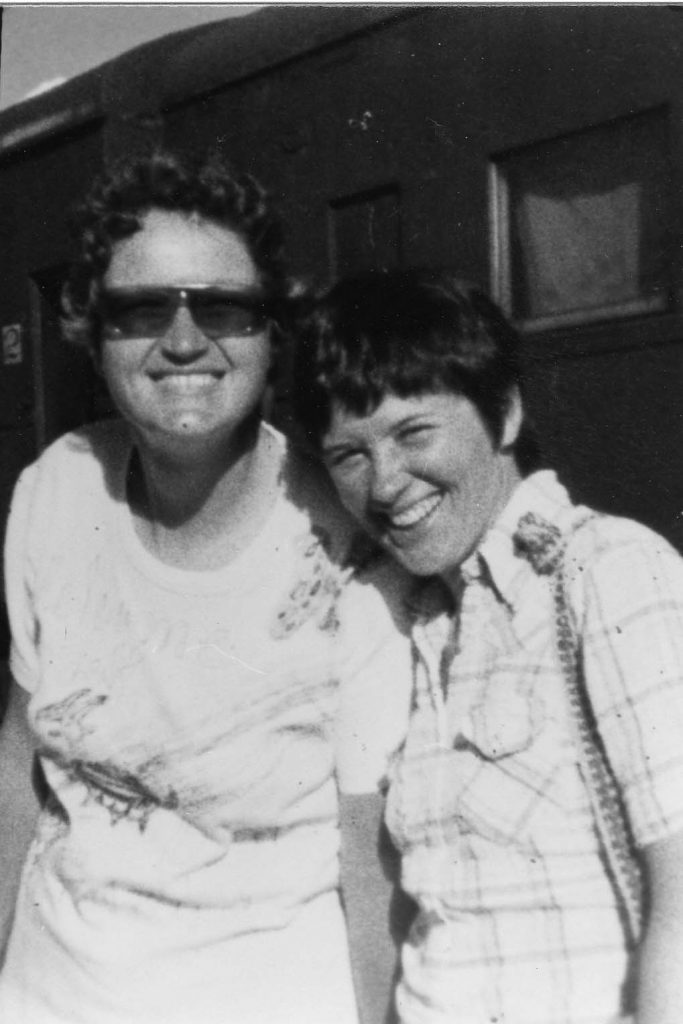

Driven by this yearning, Carla moved to La Bandera, an impoverished población (barrio) on the outskirts of Santiago in 1973, the year that the brutal Pinochet dictatorship began. There, she spent the next seven years working and living with three nuns, including Ita Ford, who became her closest friend. Their lives changed dramatically as they allowed themselves to be evangelized by their poor neighbors. When they saw mothers and children weak from hunger because their husbands and fathers were now political prisoners, they sought donations for soup kitchens, visited the men in prison, and brought their names to the attention of authorities so they would not languish there forgotten. They remained in La Bandera offering help and consolation wherever they could, subject to many of the same risks their neighbors endured.

When they saw mothers and children weak from hunger because their husbands and fathers were now political prisoners, they sought donations for soup kitchens, visited the men in prison, and brought their names to the attention of authorities so they would not languish there forgotten.

Advertisement

Carla and Ita also befriended a British doctor, Sheila Cassidy, who would soon be jailed and tortured by the Pinochet regime. In her memoir, Audacity to Believe, Cassidy describes her Maryknoll friends:

These were not pious foreign missionaries coming in to preach a message of brotherly love and then returning to their comfortable American-style house, but educated young women who lived in a little wooden house like [the people] did, who travelled on foot and by bus as they did and who shared their bread and their friendship and their talents…

The [Pinochet] coup had been a great proving time, for the nuns had stayed in their home and their house had been searched along with those of their neighbours. They had shared the terror…when the población had been surrounded and the tanks had driven between the little houses and over some of them.

In choosing to live the life of the marginalized, with all its terror, risks, and deprivation, Carla and Ita became one with them. Carla saw her own faith intertwined with that of a hungry, ill-clothed, and timid mother:

Her gentleness and patience have showed me more of the beatitudes than many sermons. Her hunger and thirst have cried out for justice more strongly than the whole United Nations. Her single-hearted struggle for her children speaks more for love than many commandments…I need her faith to help me believe. After all, I know that all the rights she has been denied—food, work, education, decent housing—exist for some people—and sometimes they forget the “least of my brethren.”

Suffering with the people took a toll on their physical and mental health, and when Carla and Ita returned to the United States for periods of renewal, their families and friends were dismayed by their condition and did not understand their discomfort with U.S. opulence and waste. Yet it was those years spent with Chileans living under a ruthless dictatorship that prepared them for the challenges they would one day face in El Salvador.

In 1979 Archbishop Óscar Romero made an urgent appeal for experienced missioners to join him in El Salvador, where he was gaining renown internationally as the courageous champion of campesinos (farmers) and laborers being murdered by Salvadoran death squads and military forces in an ever-escalating spiral of violence. Carla and Ita answered his call, but arrived too late to work with him, just after his assassination on March 24, 1980. Exploring where they might be most needed, they perceived the oppressive Salvadoran reality, but were moved by the faith they witnessed in lay catechists who dauntlessly continued to speak the truth as their own beloved “Monseñor Romero” had done.

Carla soon noticed that her own spirituality was deepening; she wrote a friend: “[In this] situation of violence, I’ve come to believe in Christ as…dynamic life which can cast out fear…I’ve seen the difference in myself…not because I’m me but because Christ does live in me.” And she composed this poignant statement of faith:

I believe that Good will win over evil,

that Creativity will win over destruction

and that Peace will win over war…

My belief in Jesus who makes all things new is growing,

God has never abandoned me—

I’ve felt alone and lonely

but I’m learning to wait and He is present even in this mess.

Thus, when the Archdiocese of San Salvador asked Carla and Ita to coordinate a refugee committee in war-torn Chalatenango—where campesinos were most in need of food, clothing, and safety—they readily accepted. They threw themselves into this dangerous relief effort, aware that it would incur the ire of powerful government and army forces who would view them as sympathetic to guerrillas fighting in the area.

Carla’s zany personality and generosity of heart drew in others. Ursuline Sister Dorothy Kazel and lay missioner Jean Donovan, two blue-eyed blondes, were working with the Cleveland Latin American Mission Team in La Libertad on El Salvador’s Pacific coast and had also responded to archdiocesan requests for help in transporting refugees. Carla and Ita often called on them because they had vehicles and because their “gringa” looks seemed to ease their way through military roadblocks. Carla, a brunette, even began to joke about bleaching her hair.

[In this] situation of violence, I’ve come to believe in Christ as…dynamic life which can cast out fear…I’ve seen the difference in myself…not because I’m me but because Christ does live in me.

—Carla Piette

Carla and Ita sometimes stayed overnight in La Libertad, and the four women rapidly became friends. Together they found support and a much needed reprieve from the suffering they were all witnessing: the mutilated bodies of men, women, and children on roadsides; the news of murdered priests, campesinos, labor leaders, and catechists; and the abductions of friends and acquaintances. While Dorothy was on vacation, Jean, Carla, and Ita had a “fun day” according to Jean’s diary, with Carla reading articles in Glamour magazine and the three of them finishing off a bottle of Chilean wine.

Four days later, Carla drowned. Jean comforted Ita and held her close at the funeral mass in Chalatenango. Also present was Maryknoll Sister Maura Clarke, who had been in El Salvador only three weeks. Moved by the testimonies of Carla’s life of sacrifice and tragic death at the age of 40 and seeing Ita’s determination to continue working with refugees, Maura immediately offered her assistance.

As a driving force in the refugee ministry, Carla had drawn in Dorothy and Jean, and, in death, Maura. Though she was only in El Salvador five months, it seemed that everyone knew of Carla’s selfless spirit—evident even in the throes of death. Dorothy later wrote that Carla’s “beliefs, her life, her whole being” was a “resurrection experience.” She was buried in Chalatenango with the “people she belonged to,” declared Ita.

Three months later, on December 2, 1980, Dorothy and Jean picked up Ita and Maura upon their return from a Maryknoll Sisters regional meeting in Nicaragua. After leaving the San Salvador airport, the four women were abducted by Salvadoran National Guardsmen. They were driven to a deserted area, where they were raped and executed. Had Carla survived the flash flood, it is probable she would have shared their martyrdom.

Statements by each of the four churchwomen following Carla’s funeral, preserved for posterity in their letters and cassette recordings, attest to how much she inspired them as they persevered in their own commitment to the “poor ole beat-up people” of El Salvador. There is no doubt that Carla’s “heroic offering of life, suggested and sustained by charity”—to quote the words of Pope Francis—places her firmly in the company of Dorothy, Jean, Ita, and Maura. Should these four martyrs be proclaimed saints in the future, Pope Francis’s new pathway to sainthood has now cleared the way for Carla to be included as the “fifth churchwoman.” Her extraordinary compassion and sacrifice in perilous circumstances should not be lost from human memory.

Photos and excerpts from Carla Piette’s writings are courtesy of Maryknoll Sisters Archives.

Add comment