The monks processed silently into their new abbey church. The faint chip, chip, chip of pick on stone grew louder, soon the slap of mortar on a wall replaced it, followed by more chipping. Upon seeing movement amid the shadows, more than a few monks blinked. The artist commissioned to create a large mosaic circling the Eucharist chapel was still working! There she was, perched high on scaffolding, determined to finish the job even though the prior told her to be out by Holy Week.

No way was she going so soon, nor was she moving rock, concrete, and equipment until the mosaics were complete. An irresistible force had met an immovable object that evening. Liturgical schedules confronted artistic imperatives. She kept chipping, and the monks kept chanting.

That chant continues more than 50 years later at Saint Anselm Abbey, located on the slopes of a mountain overlooking Manchester, New Hampshire, where the monks have come to count Sylvia Nicolas, the no-nonsense, not-to-be-pushed-around artist, as one of their dearest friends.

Nicolas, at age 92, has just completed a major project for the new Saint Thomas Aquinas University Parish, which serves Catholic faculty, staff, undergraduates, graduate students, alumni, and neighbors at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

An internationally recognized stained glass artist and sculptor, Nicolas can be intense, precise, and determined. Yet somehow it goes down as easily as the cup of tea, apple tart, and stories she offers visitors of her rambling 19th-century New England farmhouse and studio in Mont Vernon, New Hampshire, where she raised her family and has lived for the past five decades.

A native of the Netherlands, Nicolas grew up within a cultured and artistic family of her parents, Joep and Suzanne Nicolas, and sister, the late Claire Nicolas White, a noted writer who died earlier this year. Seeking to escape the rising threat of Nazi Germany, her father, often called the “father of modern stained glass,” brought his family to the United States in 1939.

When she talks about the figures she depicts, she sounds as if she is describing old friends. It wouldn’t surprise her much if her saints pulled up a chair to her table or workbench.

Nicolas travels to her homeland often to see relatives in and around Venlo. The work of five generations—from her great-grandfather to her son—can be found in the 16th-century Saint Pancratius Basilica in nearby Tubbergen. Intense color, subtle light, and dramatic gestures in more than 40 windows by the family bejewel the basilica. These include work by Diego Semprun Nicolas, one of Nicolas’ three grown children, whose own studio is in Tubbergen.

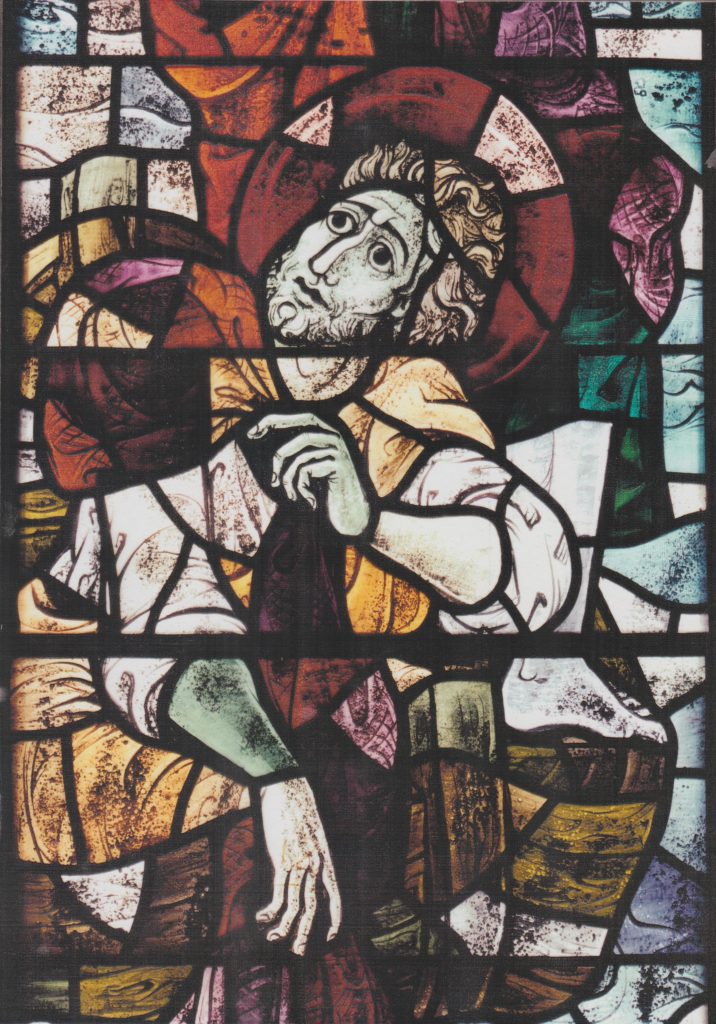

Nicolas’ drawings, mosaics, sculptures, and stained glass show a deep respect for religious, architectural, and artistic tradition but also reveal a playfulness, a kind of “reverence and irreverence,” she explains, that speaks of her desire to “express humanity.” Her figures’ faces can be amused, puzzled, annoyed, awed, even angry and despairing. Their bodies can be fat and jolly, austere and sublime. She has even done costume design. When Nicolas was 12, she wanted to be a ballerina. She eventually went on to study in Paris, where she fell in love with designing sets and costumes.

Her Catholic faith is not worn on her sleeve but shines through in why she works, what she says, and how she acts. When she talks about the figures she depicts, she sounds as if she is describing old friends. It wouldn’t surprise her much if her saints pulled up a chair to her table or workbench.

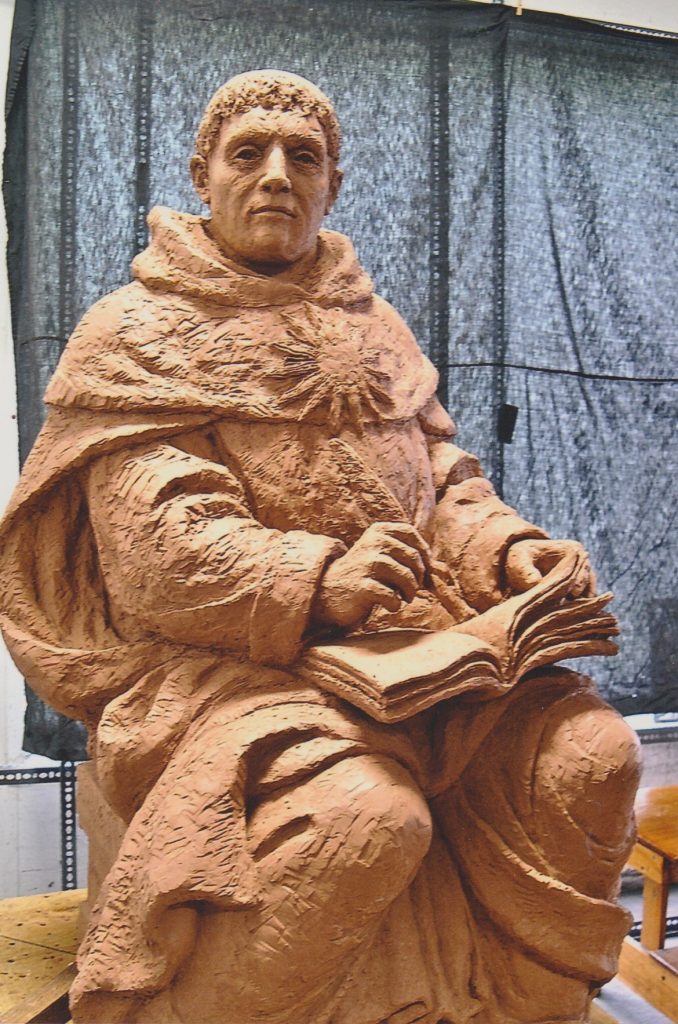

St. Thomas Aquinas has been on her mind a lot lately as she works on the Charlottesville church.

Nicolas jokes, “I wondered who he was as a person. Who was this man who worries about the number of angels who can dance on the head of a pin? He was wonderful! I spent a whole year with him, reading everything I could get my hands on.”

That research, she says, helped her visualize Aquinas as she sculpted him for a bronze figure outside the humanities center at Providence College in Rhode Island. St. Anselm, founder of the scholastic theology that Aquinas brought to such heights, was likewise a bit off-putting, she adds. Then she discovered accounts by his medieval biographer, Eadmer.

“Why did no one ever tell us these stories? They make the great figures of the church, such as Augustine, Anselm, and Aquinas, so human. They make you want to go to them to learn, discover, and believe,” Nicolas says.

In a talk Anselm once gave his monks at Canterbury, the archbishop lamented how much time with his community was lost to the bureaucracy of church administration and attention to the king. He remembered his time at Bec, the abbey in Normandy in France, where he served as a monk and later abbot and did some of his best theological, philosophical, and literary work. But having been summoned to England to serve in Canterbury, Anselm realized his love for the cloister, likening his concern for his monks to the way a mother owl cares for her chicks.

The story makes her sigh and smile, Nicolas says. She made sure that in her bronze figure of Anselm, the saint looks out toward the future with an owl cozily nestled in the crook of his crozier. “In the end, I think I’m a storyteller,” she says.

“Why did no one ever tell us these stories? They make the great figures of the church, such as Augustine, Anselm, and Aquinas, so human. They make you want to go to them to learn, discover, and believe.”

Nicolas is responsible for three stained glass windows behind the main altar in the Charlottesville church as well as the bonded bronze crucifix over the altar and the stations of the cross. Her stylus made minute changes in the clay mold for a final station. The station at some level expresses who she is, reveals something of divine love, and speaks to those praying before it, contemplating the passion of the Lord. Such encounters with art can lift and transform the human heart.

For Nicolas, great issues of justice, truth, and mercy need attention, but they are not more important than the condition of the heart. Indeed, a heart open to Christ in prayer leads to service, change, and reform.

“Art requires subtlety,” she says, “not sentimentality.”

The artist’s work “can’t shout out loud, ‘Hey, have you seen me?’ and forget about the rest of the church. The artist must understand the architecture. You are serving the architecture and the space,” she says, mentioning several artists whose work is widely known but who lack the understated approach she values.

Her workshop in the barn is piled high with works in progress, clay models, supplies, easels, and tables for her to work on multiple projects. There is no glitz or fancy lighting, just big and drafty windows, a couple of space heaters, and lots of shelving.

Nicolas’ work graces colleges, universities, parish churches, chanceries, monasteries, government buildings, hospitals and hospices, convents, and parks across the country. She tells visitors to her website that she does “not want to become set in preconceived ideas. I want to be open to the spontaneity and accidents of the medium. Very often the medium will tell me where to go.”

This article also appears in the December issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 85, No. 12, pages 45-46). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Header Image: Jim Dachowski

All other images courtesy of Sylvia Nicolas

Add comment