The Catholic Church is often referred to as a “big tent” under which people of all backgrounds and perspectives can gather together in faith. In the literary world, the Jesuit-educated Irish writer James Joyce described this vision of the church as “Here comes everybody.”

This vision is the ideal, but in reality some voices and perspectives are often marginalized or drowned out by others—especially when it comes to stories about faith and identity and who gets to tell whose story.

Ask people to think of a “Catholic writer,” and many people will think of someone of white, European heritage, such as Joyce, Flannery O’Connor, or Graham Greene.

These are all great writers, but by limiting the example of Catholic storytelling to writers of a similar background, we lose the full range of stories that spring from the Catholic imagination. We lose out on the stories that can only be told by Catholic writers of more marginalized backgrounds, such as Toni Morrison or Louise Erdrich.

Likewise, earlier in 2020 there was controversy about the book American Dirt (Flatiron Books), a novel about Mexican-U.S. immigration written by an author who is not an immigrant or of Mexican heritage. The controversy led many readers to seek out books by Mexican American writers or immigration stories by authors with more immediate knowledge of what it means to be an immigrant today: In other words, stories by authentic voices.

With that in mind, the U.S. Catholic editors selected a few recent books written by authentic literary voices. These books come from writers who are Native, Latino/a, African American, Caribbean, working-class, LGBTQ, and disabled. Some speak directly about faith and Catholicism, and some come at the spiritual element of their stories from an indirect angle. All are authentic stories of faith and identity worth telling and reading.

NONFICTION

Rust: A Memoir of Steel and Grit

By Eliese Collette Goldbach (Flatiron Books, 2020)

As a Millennial attending Catholic school, Eliese Goldbach grew up hearing that she could do anything and be anyone she wanted to be. But when Goldbach graduated right before the Great Recession with a bachelor’s degree in English, she quickly discovered that her options were limited. A few administrative tasks away from her Ph.D., with no job prospects in sight, Goldbach eventually applied for one of the remaining stable, well-paying jobs in Cleveland, the city where she grew up: at the steel mill.

In her new memoir, Rust: A Memoir of Steel and Grit, Goldbach writes about the three years she spent working in the steel industry, a period spanning the 2016 election and the inauguration of President Trump. With generosity and love, she complicates the stereotypes of the white, Midwestern union member we heard about so often during the last election and instead blurs all kinds of class, gender, political, educational, and age divides. She writes unflinchingly of her own life on topics ranging from sexual abuse at Catholic universities to the failures of our country’s mental health system to what it means to be truly poor in today’s society.

Whether you’re drawn to this book for its in-depth descriptions of steel production or for Goldbach’s depiction of her blue-collar, Midwestern, Catholic family, Goldbach will engage you with her honest storytelling about what it means to be a Millennial, a woman, a daughter, and a person of faith in today’s world.

Lost, Found, Remembered

By Lyra McKee (Faber & Faber, 2020)

Lyra McKee was only 29 years old when she was killed during a riot in Derry, Northern Ireland in 2019. A rising star journalist, McKee was doing her job when she was killed: covering the latest outburst of sectarian violence in her home country. Before her death, McKee garnered recognition for reporting on the persistence of violence in Northern Ireland decades after its historic 1998 peace accord, known as the Good Friday Agreement. Indeed, McKee was killed just days after the agreement’s 21st anniversary.

Lost, Found, Remembered collects the best of McKee’s journalism as well as her lesser-known articles and unpublished material. A native of Belfast, McKee was born four years before the 1994 ceasefire by the Provisional Irish Republican Army and eight years before the Good Friday Agreement.

In Northern Ireland the people born during this era are known as “the Ceasefire Babies.” As McKee notes, her generation was supposed to reap the benefits of peace after the end of “the Troubles,” the decades of conflict between Protestants favoring union with Great Britain and Catholics campaigning for independence from Britain and incorporation with the Republic of Ireland. Instead, as McKee reported in 2018 in the Belfast Telegraph in one of her most famous pieces, “The Ceasefire Suicides,” the North has lost more people to suicide since the peace agreement than it had in the previous 30 years of conflict. McKee was one of the first reporters to bring such stories to light.

McKee also wrote articles reflecting on her experience coming out as gay. Among the most touching of these is a 2014 essay published in The Muckraker, “A Letter to My Fourteen-Year-Old Self,” which begins, “Kid, It’s going to be okay.” Two years later she published an op-ed in a Belfast newspaper about a local bakery that refused on religious grounds to bake a wedding cake for a same-sex couple.

Strikingly, McKee calls for conversation with the people who hate people like her: “If I could sit down with [them] tomorrow, I wouldn’t tell them I hate them, because I don’t. I’d just want them to know that I’m just like them and that, if God exists, I’m fairly certain He loves me, too.” Overall, this book is a heartbreaking memorial to a courageous voice lost far too young to a conflict that must finally end.

The Toni Morrison Book Club

By Juda Bennett, Winnifred Brown-Glaude, Cassandra Jackson, and Piper Kendrix Williams (The University of Wisconsin Press, 2020)

A book club meeting often brings to light new perspectives as well as opportunities to push, prod, and challenge our friends. For the four writers of The Toni Morrison Book Club, conversation around Morrison’s novels did just that. In this engrossing collective memoir, a diverse group of memoirists use four of Toni Morrison’s novels—Beloved, The Bluest Eye, A Mercy, and Song of Solomon—as framework for intimate conversation and a moving reflection on race.

Comprised of essays contributed by Juda Bennett, Winnifred Brown-Glaude, Cassandra Jackson, and Piper Kendrix Williams (all professors at The College of New Jersey), the memoir is an intellectually rich but accessible meditation on Morrison’s works. The four novels selected are each the subject of two essays by different memoirists, whose varied reactions offer deep insight into their own backgrounds.

Brown-Glaude, writing about Song of Solomon, reveals her fears as the mother of a Black son and the struggle to survive whole. “I don’t want to just survive but I want to wish and hope—with the help of Morrison—to survive whole,” she writes. “I am writing as an act of surviving whole.” Bennett, the volume’s sole white contributor, writes in his reflection on Song of Solomon that his first time reading it “felt like both an open door but also a disturbingly shut and locked door to some secret thing I was missing.”

While the writers acknowledge there are already plenty guides to Morrison’s work—“too many to count,” they say—Piper, Winnie, Cassandra, and Juda’s stories are guides as well, revealing secrets and tender truths that will surely open doors for many readers.

The Undocumented Americans

By Karla Cornejo Villavicencio (One World, 2020)

“I am not a journalist. Journalists are not allowed to get involved the way I have gotten involved,” writes Karla Cornejo Villavicencio in The Undocumented Americans, her new book detailing the lives of undocumented people in the United States.

And it’s true: Villavicencio, an undocumented American and DACA recipient herself, does not write like a journalist. Instead, these pages ring with empathy, heartbreak, and righteous rage, whether she’s talking about the undocumented workers who cleaned up Ground Zero after 9/11, the families in Flint, Michigan who are unable to receive clean water without a state ID, or the desperate patients seeking health care for everything from migraines to cancer to mental health diagnoses at botanicas, natural health shops that are the only option for many without insurance.

The parts of the book that remain with the reader the longest are those that are also hard to read. Villavicencio describes how a therapist once told her that when kids are separated from their parents at a young age, their brains are flooded with stress hormones and never develop. “One psychiatrist I went to told me that my brain looked like a tree without branches,” she writes. “So I just think about all the children who have separated from their parents . . . and I just imagine us as an army of mutants. We’ve all been touched by this monster, and our brains are forever changed, and we all have trees without branches in there, and what will happen to us?”

Despite looking unflinchingly at the trauma inflicted on undocumented Americans, Villavicencio’s book is also a love letter to the people on whom, in many ways, our nation stands. She brings the people in her book to life, describing their religious faith, their relationships with their children and pets, and the small events of their daily lives. Her book puts a face to “the mass of undocumented people” in this country and reminds readers that they are human beings with their own hopes and dreams.

POETRY

In the Field Between Us

By Molly McCully Brown and Susannah Nevison (Persea Books, 2020)

After meeting at a writers’ conference in 2016, poets Molly McCully Brown and Susannah Nevison became fast friends. Along with a shared craft, both women have a physical disability. Within a year of meeting they began collaborating, publishing epistolary essays and poems that challenge traditional narratives about disability.

In the Field Between Us is their first full-length collaboration—a collection of poem-letters about friendship, disability, nature, and belonging. Although not a religious collection, its themes can also be understood as community, human dignity, creation, and solidarity. Brown is a Catholic whose essay collection Places I’ve Taken My Body (Persea Books) explores faith, and she and Nevison both approach their imagery in this collection with a strong spiritual sensibility. Their poems employ the same nature images—birds, trees, rivers, bones, and stars—testifying further to the sense of conversation and the communion of their experience.

The poems are divided into chapters titled “Aftermath,” “Recovery,” “Operating Room,” and “Pre-Op Holding Room.” Each chapter ends with poems addressed to a “Maker” figure, who is all at once doctor, artist, mother, and God. Notably, this Maker is not a figure whom the poets call upon out of self-pity or for healing, but one who serves as a witness to each poet’s individual understanding of their shared experience of suffering as well as friendship.

Postcolonial Love Poem

By Natalie Diaz (Graywolf Press, 2020)

In an interview with the Rumpus, Natalie Diaz described her brand of Catholic faith as “not the Catholicism that most people would recognize. It’s rezzed out. It’s jalopy.” Born in the Fort Mojave Indian Village in California, Diaz is a Mojave poet who played professional basketball abroad before publishing her first collection of poetry, When My Brother Was an Aztec (Copper Canyon Press), in 2012. That collection—with its fusion of pop culture, Native American myths, family pain (specifically, her brother’s drug addiction), and Catholicism—announced a major new voice in poetry.

Diaz’ second collection, Postcolonial Love Poem, is another powerful offering with many of the same themes of her first collection, but with more focus on love and relationships (especially from a queer perspective) and creation (especially its conquest and colonization).

Water, for example, appears again and again: the dammed and polluted water of the Colorado River; the poisoned water supply of Flint, Michigan; the threatened water supply of the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation; and even the absent water of drought, thirst, and ancient seas turned to deserts.

But water is also a life source, a lover, a mystery, humanity, and a spiritual force, as in “exhibits from The American Water Museum”: “Only water can change water, can heal itself. Not even God / made water. Not on any of the seven days. It was already here. / Or maybe God is water, because I am water, and you are water.”

In poem after poem, Diaz skillfully mingles the language of romantic love, heartbreak, and spiritual reverence with imagery of the Earth, solar system, and human body, suggesting all are intimately connected.

FICTION

Afterlife

By Julia Alvarez (Algonquin, 2020)

Antonia Vega is a recently widowed, new retiree struggling to find her identity without the companionship of her do-gooder doctor husband, Sam, and daily interaction with her English literature college students. Her belonging to “the Sisterhood”—a complex yet unbreakable bond with her sisters Izzy, Mona, and Tilly—remains a comforting constant in her life, but even this relationship is challenged and irreversibly changed by the story’s conclusion.

As Antonia navigates rediscovering who she is in the world without relying on who she is in relation to those who no longer exist around her, she draws upon the words of literary companions who have often served as her guides. Who she is—who she has always been—emerges in new ways as she builds unexpected friendships with the town sheriff, a local doctor, and the undocumented immigrants living next door.

Repeatedly asking herself “What would Sam do?” morphs into “What is the right thing to do?”as Antonia realizes perhaps the best way to honor her late husband is by being uniquely herself—a 66-year-old Dominican woman living in rural Vermont with experience, connections, and compassion for those whose stories intersect with hers, even if just for a short while.

In Afterlife, the talented Julia Alvarez—herself an immigrant from the Dominican Republic and a central Vermont-based writer—shares Antonia’s story with eloquent and poetic prose that invites the reader into the protagonist’s mind, full of conflicting and incomplete thoughts as well as precise literary references and profound revelations. This same complexity accompanies many of the characters crafted into Afterlife’s scenes, realistically portraying a community and its members, none of whom can be readily identified as hero or villain. In fact, it may just suggest that we are all good people trying to do what’s best.

This Town Sleeps

By Dennis Staples (Counterpoint Press, 2020)

On its surface, This Town Sleeps is a somewhat formulaic ghost story. It centers around Marion Lafournier, a 20-something, gay, Ojibwe man coasting through life after moving back to his hometown. One night, he accidentally brings to life the spirit of a dog from beneath the elementary school playground, which, in turn, leads him to investigate the decades-old murder of a local high school basketball star.

But read a little closer and you discover the story is not about Marion but about Geshig, the Ojibwe town where Marion lives. Staples tells each chapter from the perspective of a different character, showing how townspeople of different genders, sexualities, ages, and spiritualities make a life for themselves and how violence and trauma affect the communal life of a community across generations.

Altogether, Staples’ book will appeal to a wide audience, whether you’re looking for a magical realist story about a spirit dog and solving a long-covered-up murder or a nuanced portrait of a modern Native American community and the myriad ways there are to be Native today.

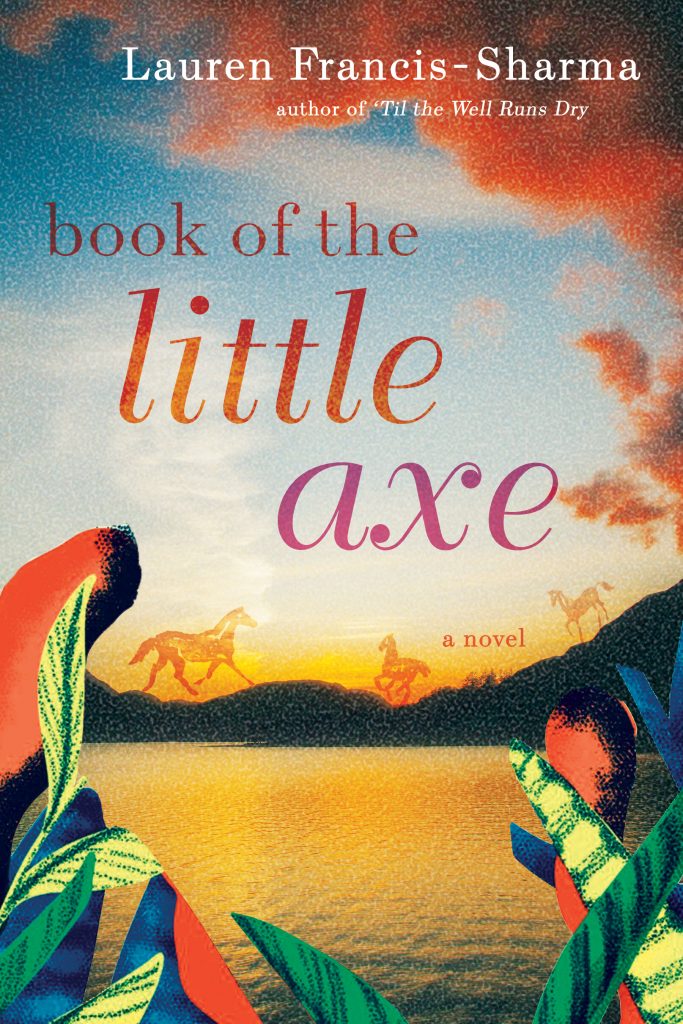

Book of the Little Axe

By Lauren Francis-Sharma (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2020)

Book of the Little Axe is both an old-fashioned epic historical novel and a truly original coming-of-age story. It begins with the tale of an Apsáalooke (Crow) boy growing up in the American West in the 1830s. Victor is on the cusp of manhood: If only he could have the vision that boys his age must receive before moving on from childhood. His father is a tribal chief, and his mother is a Caribbean woman with a mysterious past. After a runaway girl enters their village escaping from slavery, Victor begins asking his mother questions about his own history. Victor’s mother, Rosa, decides it’s time to take her son into the wilderness to begin his vision quest.

From there the story backtracks to 1790s Trinidad, Rosa’s homeland, and begins to piece together her own history. Rosa’s mother is from a family of mulatto settlers from Martinique, and her father is a blacksmith and farmer from Africa. Rosa prefers to help her father with their horses than perform domestic work like her elder sister. The family enjoys a comfortable life, but when Trinidad transfers from Spanish to British rule, the family’s fortune changes for the worse. Their status as free Blacks during the height of the transatlantic slave trade is increasingly challenged. And as a girl who doesn’t fit into traditional gender roles, Rosa’s freedom is at risk in more ways than one.

There’s also a misfit tracker named Creadon Rampley, the orphaned child of a Crow woman and a white man, and a charmer named Edward Rose, a real-life fur trapper of African and Native heritage. How all these characters come to meet in Montana is only part of the story’s purpose.

In this second novel by Lauren Francis-Sharma, a first-generation Trinidadian American, attorney, and mother who published her first novel, ‘Til the Well Runs Dry (Picador), when she was over age 40, is a refreshing challenge to simplistic stories of American colonialism that favor storylines driven by European males. What Francis-Sharma offers instead is a unique and gloriously complex Western that you won’t be able to put down and whose characters you won’t soon forget.

Image: Eliott Reyna on Unsplash

Add comment