When I was little, one of my favorite book series was the Emily of New Moon books by Lucy Maud Montgomery. The main character loves to write and makes friends with the trees in her backyard, and I identified with both these traits. But along with our shared personality traits, I felt drawn to the main character by our shared physical traits: Like me, Emily has wild black hair and pale skin, not to mention our shared first name.

Throughout my childhood, I didn’t have to look very hard to find characters who looked like me. My favorite books included the Boxcar Children and The Chronicles of Narnia, the Chronicles of Prydain and the Anne of Green Gables books, The Secret Garden and The Little Princess. In other words, books that were filled with feisty and independent girls who went off and had adventures. Girls who also just happened to be white.

In the days, weeks, and months since the death of George Floyd and the protests for racial justice and equality around the nation, you may have seen the phrase decolonize your bookshelf floating around the internet. Beneath the jargon, the phrase asks us to take a look at our personal libraries and see what books, characters, and authors have built our literary worldviews. How many authors are people of color? How many of them come from backgrounds different than our own?

What books have built your literary and theological worldview?

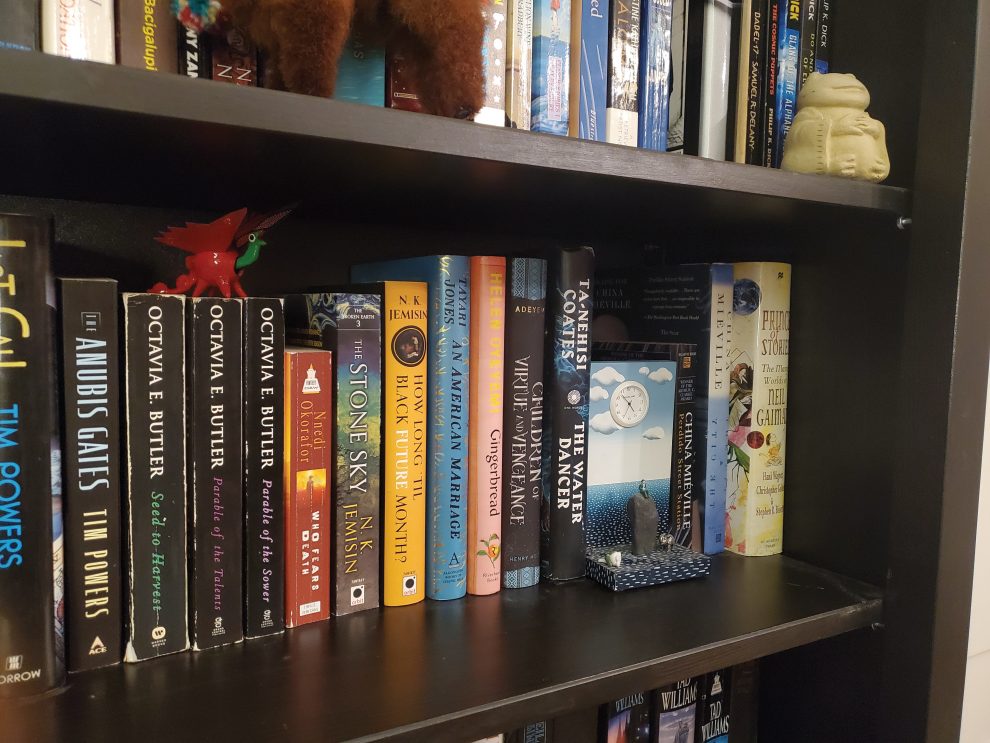

I have to admit: When I first started seeing the memes and suggested reading lists, I felt a bit smug. Emily of New Moon may still be on my bookshelf (or bookshelves to be more accurate—let’s be honest, I have a bit of a book problem), but a quick scan confirmed that a good portion of my novels are by writers of color such as N. K. Jemisin, Octavia Butler, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Louise Erdrich, and Alice Walker.

And then I got to my religion bookcase, which holds my books from seminary—books on scripture, theology, and ministry. In other words, the books that I pull out and use as resources to brainstorm story ideas or to write this column. And sure, I have a couple classics by people of color—The Cross and the Lynching Tree by James Cone, for example, or Jesus and the Disinherited by Howard Thurman. But overall my available resources are predominantly by white authors and from a white point of view.

When I pulled out one of the few exceptions—The Africana Bible, edited by Hugh R. Page—I was reminded why it is so important to decolonize our bookshelves, both generally and in terms of the religious books and media we consume.

As I flipped through the book, which includes essays by Black scriptural scholars reflecting on each of the books of the Hebrew Bible, I found my perspective on even the most familiar stories changed. One article places Leviticus’ rules against the background of civil rights movements with their chant, “No justice! No peace!” Another reflects on the prophet Isaiah through the lens of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa. A third compares the Book of Jonah to the work of Zora Neale Hurston.

The movement to decolonize our bookshelves reminds us that we are shaped by the stories we read. And if this is true for novels, how much more is it true for the sacred stories we use to make sense of our place in God’s creation?

If we read or listen to only one cultural perspective of our scripture or theology, it is easy to forget that our faith has been used to justify slavery, violence, and cruelty. On the flip side, it is also easy to forget that our faith is a global one. Indeed, our scriptures were written by people of color, not by white Europeans.

Reading books—whether novels or scriptural commentary—by authors of color certainly won’t solve racism. But it may help white Catholics to see the world through a new perspective, just for a little bit. It may make your image of God a little bigger. And that is never a bad thing.

This article also appears in the September issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 85, No. 9, page 7). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Emily Sanna

Add comment