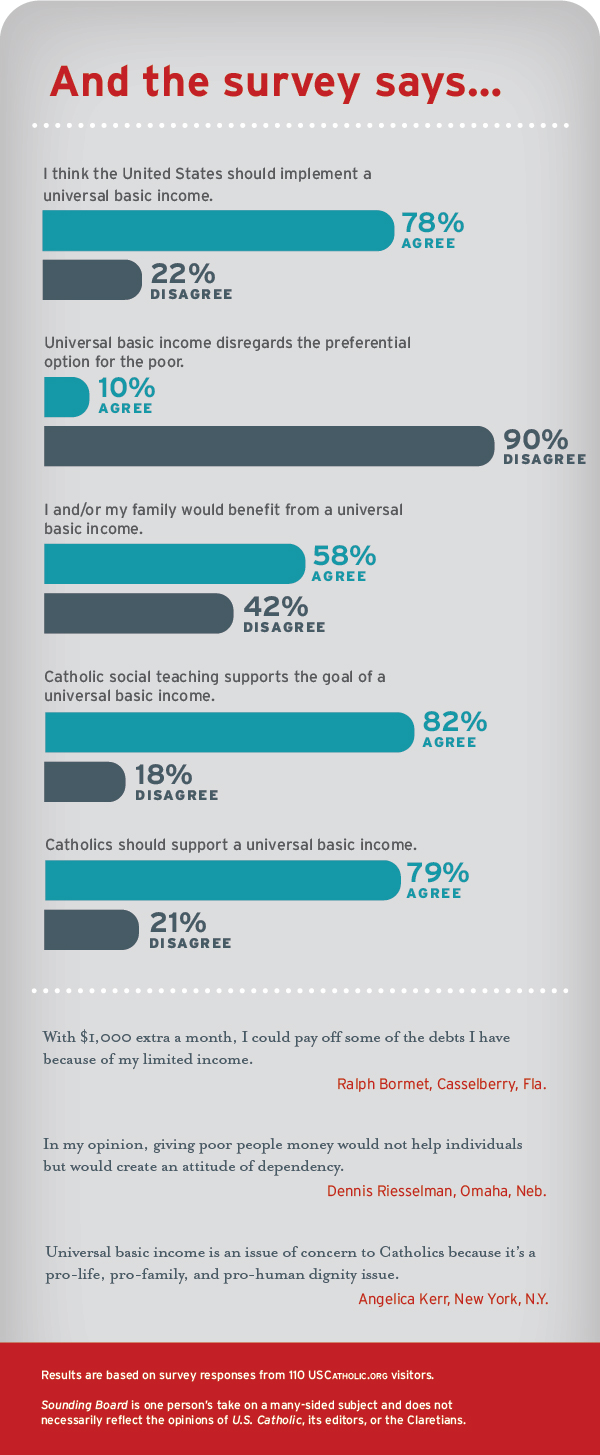

What would you do with an extra $1,000 a month?

Lorrine Paradela, a participant in a basic income experiment in Stockton, California, was able to fix her car after an accident, protecting her ability to get to work and visit family. Freed of the need for a second job, she started attending more of her son’s football games. Some of us might build a savings account, support local causes, or finally take a vacation. Money like this would help others dream even bigger—to move into their own place, start a business or a family, retire, or earn a degree.

This is the promise of universal basic income (UBI), a proposal to give each member of society a monthly infusion of cash, tax-funded, with no strings attached. This seemingly utopian proposal has an array of practical benefits to recommend it—and an impressive list of supporters, including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., President Richard Nixon, libertarian economist Milton Friedman, and CEO-turned-presidential candidate Andrew Yang.

Pope Francis joined that list when he observed, as the novel coronavirus pandemic raged, that “this may be the time to consider a universal basic wage.” What could such a broad range of thinkers find to like in such an out-there idea, and why should Catholics care?

Alleviate poverty and meet basic needs

Fundamentally, UBI is an antipoverty proposal. That’s where the $1,000 per month figure comes from: It would keep most members of society out of poverty. (The federal poverty level for a single person is currently $12,760.) Making the benefit universal reduces stigma. Generally, UBI is envisioned as replacing other social safety net programs, such as food and cash assistance and unemployment or disability benefits. Certainly, prudence would be required to ensure that those in need don’t end up worse off—for example, health care might be provided separately. UBI could be taxed at a graduated rate so that those with very high incomes end up “returning” their basic income to the common fund.

Catholics can gladly support government programs to help the poor meet their basic needs. According to Catholic social thought, every human has innate dignity as a creature of God and the right to attain basic needs such as food, shelter, and clothing. God’s followers in the Bible are told to take special care of the “orphans and widows,” those who can’t support themselves through their own work.

There are many reasons why families today can’t meet their basic needs through work, from disability to insufficient employment to unjustly low wages at the jobs they can find. To help folks in this situation meet their basic needs, the community is called to step in. Since government is a shared project of the people, providing support through government programs is just another way that communities can take action.

What about work?

Some UBI skeptics worry about its potential impact on work. If people could live (albeit frugally) without paid jobs, would mayhem result? Certainly, we wouldn’t want a society without doctors, teachers, or garbage collectors. But the concern that we’d see a mass exodus from useful activity rests on a fundamental misunderstanding of human nature.

Economists believe that people are motivated by money and work only because if we were not, we would starve. But the Catholic tradition understands that when we work, we act out our human nature, which is profoundly social, creative, and in the image of God. We grow in ways that are uniquely human: “creativity, planning for the future, developing our talents, living out our values, relating to others, giving glory to God,” as Pope Francis says in Laudato Si’ (On Care for Our Common Home). The ultimate purpose of work is not to earn wages, keep ourselves busy, or even make ourselves useful to society, but to be the type of creature God made us to be: creative, active human beings collaborating with others.

Many types of work that the Catholic tradition holds in deep respect are rarely, if ever, done for pay. Artists work when they create, parents work when they care for kids, and volunteers work when they plan community events—even though no one earns a wage or answers to a boss. We want to spend time on these important activities not because someone offers to pay us, but because of our human drive to communicate, connect, and create. If we look at work in its fullest Catholic understanding, UBI isn’t antiwork. Instead, it promotes work, giving everyone a little more breathing space to do the work that connects, creates, and cares.

In a course I teach, “Theology and Economics,” my students and I apply the Catholic tradition on work and human nature to contemporary economic issues. My students sometimes surprise me with their pessimism about human nature, but they have no trouble agreeing that people would continue to want to work, both for wages and “for free,” while receiving a UBI. While most agree that the human drive to connect, create, and care is not solely called forth by waged employment, they also point out, quite practically, that many workers would prefer a higher income than a UBI would provide. But for artists or students willing to live frugally, for families who want to have a parent at home with the kids but can’t afford it, or for anyone who needs to pause a busy career to deal with health issues, UBI would be life changing.

As Pope Francis pointed out, a UBI could be extremely valuable not only to those who do work that’s traditionally unwaged, but also to those who face seasons of disruption in their waged employment. With or without a basic income, the face of waged work is about to change radically—and soon. As more and more complex tasks can be done with artificial intelligence, millions of U.S. workers alone could lose jobs to automation in the next decades. According to NPR’s Planet Money, the most common job in 29 U.S. states is truck driver—and driverless cars are already on the roads. This is to say nothing of shocks such as the 2008 financial crisis or the novel coronavirus pandemic, when the U.S. government followed the logic of UBI by issuing checks to ordinary Americans.

The coronavirus stimulus payment was done for a practical reason: Cash flowing through the economy benefits us all. When wealthy people get more cash, they save it. When ordinary working people, let alone the poor, get more cash, they spend it on groceries, rent, utilities, tuition, and more, keeping a whole host of industries afloat.

According to Catholic social thought, people and programs should follow God’s own “preferential option for the poor,” putting those most in need at the forefront of our care and action. Some theologians argue that UBI fails by this standard, since it is universal instead of focused on those who need it most. But if we conclude as a society that a policy such as UBI is the most effective way to get assistance to people who are poor—whether because of efficiency, stigma reduction, or political popularity—that seems to me to outweigh the concern that others will be helped too.

The most challenging thing for many when it comes to UBI is confronting the idea that someone might receive it and never do anything useful at all. Sure, we might say, I’m cool with my tax dollars supporting single parents or striving artists, but what about someone who will just take a UBI and play video games all day? Shouldn’t people receiving help do something, somehow, to deserve it?

This view is understandable, but I’d urge my Christian siblings to give it another look. The central mystery of Christianity is a gift to the undeserving. Pope Benedict XVI urged us to shape economic life on “the logic of gift,” emulating the grace that God gives to humans freely despite our utter inability to deserve it. This doesn’t mean we all need to embrace UBI if we can come up with better ways to boost the economy, support families, and get needy people help. But I think it does mean we can’t reject proposals simply on the basis that they might help the undeserving. In theological terms, we’re all undeserving, yet God offers us help. How can we fail to extend the same grace to everybody else?

Image: Unsplash cc via Ehud Neuhaus

Add comment