For the most part, a professorship is well suited to family life. The hours are flexible and schedules are not year round. However, because a typical academic schedule is compacted into 15-week segments, there is little wiggle room inside those semesters. Many professors who wish to become parents plan accordingly, but nature does not always work on our timeline.

I was hugely pregnant near the end of the school year for one of my pregnancies and, knowing the challenges of finding anyone to cover classes deep into a semester, I gritted through the first stages of labor in front of a classroom full of students. Bending forward slightly and gripping the lectern, I hid my labor from my students who I was sure would be thrown into a panic if they knew what was happening with my body. My husband met me outside my classroom door and we reached the hospital in time, my students none the wiser.

But the fact remains that I felt trapped by the nature of the professorship, which largely does not have a protocol for female faculty creating new life.

While many schools are working toward truly Catholic leave policies, they must contend with troubling facts regarding tradition as well as limited finances that impact how full-throated their efforts can be. Historically, health benefits have been dictated by three factors that continue to impact female faculty today. The first is that the majority of faculty, both then and now, is male. In 2015, women held only 32.4 percent of faculty positions in colleges across the country. These numbers drop precipitously as we go back in time. While this is true of all colleges, Catholic universities have additional factors impacting the lack of family-driven policies specific to our faith.

In Catholic higher education, faculty and administrative positions have often been filled by childless men and women whose concerns fail to imagine the realities of family life. Catholic laypersons in administrative positions may seek to further limit fulsome policies, clinging to the belief that mothers belong at home rather than in front of the classroom.

In 2015 the Catholic Church started responding to this issue when Pope Francis asserted that businesses must “pay special attention to the quality of employee’s working life . . . in particular to encourage a balance between work and family life.”

“I am thinking especially of female workers,” Pope Francis went on to say. “The challenge is to protect their right to a job that is given full recognition, while at the same time safeguarding their vocation to motherhood and their presence in the family.”

“The woman,” Pope Francis continued, “must be protected and helped in this dual task: the right to work and the right to motherhood.”

Possibly in response to Pope Francis’ directive to support both a woman’s right to work and her right to motherhood, in 2015 Chicago Archbishop Blase Cupich rolled out a parental leave policy that genuinely supports the vocation to parenthood. His new policy offers 12 weeks paid parental leave to the 7,000 employees in his diocese and aims to bridge the gulf between the church’s pro-family rhetoric and lack of available economic support.

And yet the sea change is slow to lap up on the shores of U.S. Catholic universities and colleges. I sent an inquiry to a sampling of 20 Catholic schools, ranging in size and order, and found that less than half have actual maternity policies. The majority rely on sick leave and short-term disability to provide a slipshod management of the needs of a new mother or father.

While the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 requires employers to allow both male and female employees 12 weeks off after the birth or adoption of a child, this is unpaid leave. Going without pay for an extended period of time just as a new member joins a family is generally not within the scope of a family’s budget, making a real maternity or family leave policy a necessity.

An example of the slipshod management of these policies was found at one university where a faculty member gave birth at the end of December and learned she was allowed two weeks of sick leave, with the clock starting at the moment of delivery. After that any time off she might need to tend to the needs of her new family would result in a 50 percent reduction of pay. What makes this a unique problem for the college professor is that the weeks surrounding Christmas are already time off in university life. Rather than using her two weeks at a more advantageous time, she was required to use up sick time during a period when her colleagues were on break and then return to work far earlier than is recommended for either mother or baby.

Other Catholic schools are doing better. Christina Safranski is a math professor who has experienced family-forward policies at both St. Vincent College in Pennsylvania and Franciscan University of Steubenville in Ohio where she currently teaches. At both schools, she felt fully supported in their policies and “in their ability to work around policies,” she says, giving as an example the willingness of her department chair to manipulate her teaching load to allow half a semester of paid leave and provide an extra office space where she set up a playpen for her daughter post-delivery. She recognizes “there’s a difference between the institutional polices and the people you’re working with,” but says that “without exception, whatever the policies have been, the people have been awesome. Of course, we’re always working toward the future, for the better.”

Daniele Arcara, chair of the math department at St. Vincent and father of eight, believes that “since the family is considered very important in the Catholic tradition, Catholic universities should set a good example when it comes to allowing a mother to have a significant amount of time to bond with her newborn child(ren).” Schools, he argues, should be “generous and accommodating.”

In Laborem Exercens (Through Work), Pope John Paul II speaks of women and work, saying, “The true advancement of women requires that labor should be structured in such a way that women do not have to pay for their advancement by abandoning what is specific to them and at the expense of the family, in which women as mothers have an irreplaceable role.”

Traditionalists have never been comfortable with the word feminist, but as Safranski argues, “At its heart, feminism just means promoting and upholding the dignity of women. And that is absolutely a Catholic thing.” The way we do that, just as Pope Francis and Pope John Paul II assert, is to honor both a woman’s call to work and to motherhood. The question is if Catholic colleges and universities are ready to answer that call in supporting the family unit and the reality of female faculty.

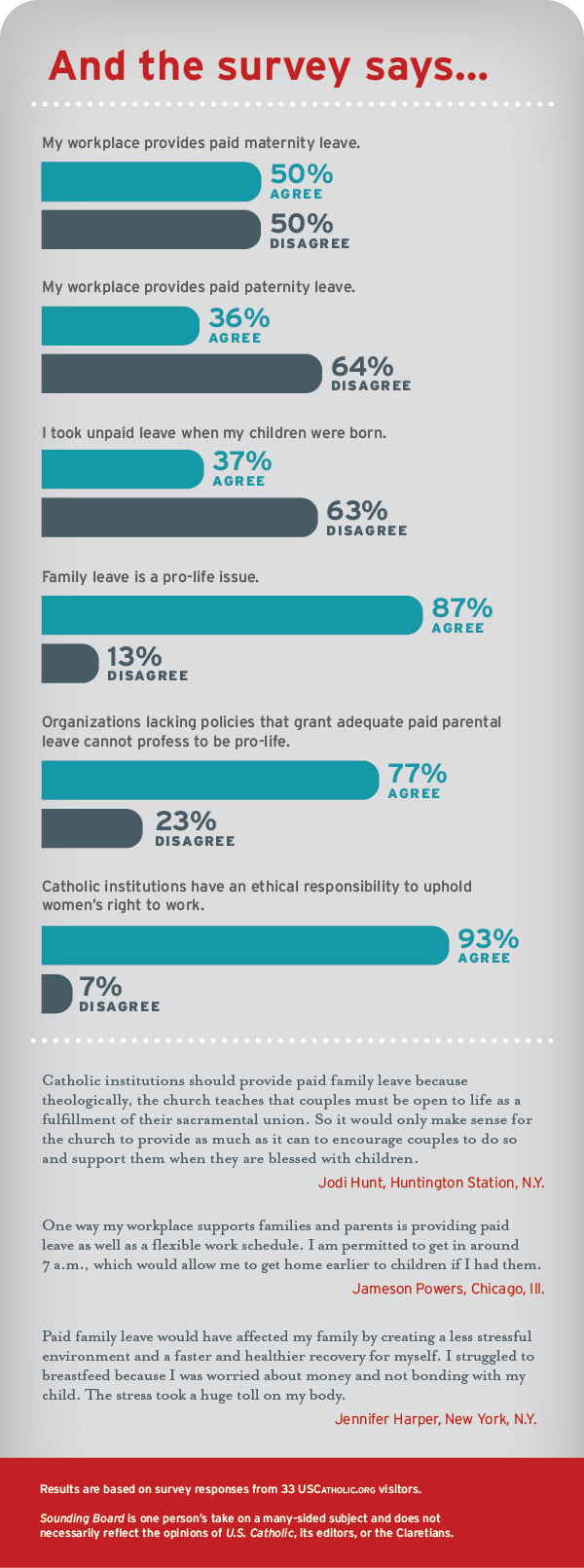

Universities lacking policies that recognize God’s rich and diverse calling to women cannot say they are upholding the dignity of women. Universities lacking policies that grant adequate paid leave after having a baby cannot profess to be pro-life. And universities with policies that do not extend paid leaves to both parents cannot be considered pro-family. If we are true evangelists, we cannot leave our faith at the doors of our Human Resources offices.

This article appeared in the August 2019 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 84, No. 8, pages 23—25).

Add comment