Spiritually, the Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris has been an important prayer space in my life. Vespers in that space was a privileged moment in which I felt the transcendence of God in a palpable way. And so, in shock, I anxiously watched and prayed as firefighters worked to save what they could from April’s tragic fire. I breathed a sigh of relief when first glimpses after the fire showed that the worst had been avoided and that much of the cathedral, including a magnificent 13th-century rose window, remained.

Interpretations of medieval Christianity and the historical import of spaces like Notre-Dame are complicated. The immediacy of those linking the fall of the spire to the fall of Western civilization demonstrates the moral ambiguity of many religious spaces, especially historic ones. The shores of the Seine were lined with Parisians praying and singing the Salve Regina, yet this was somehow not authentic. The experience, it seemed, could only be authentic if it conformed to a particular brand of faith.

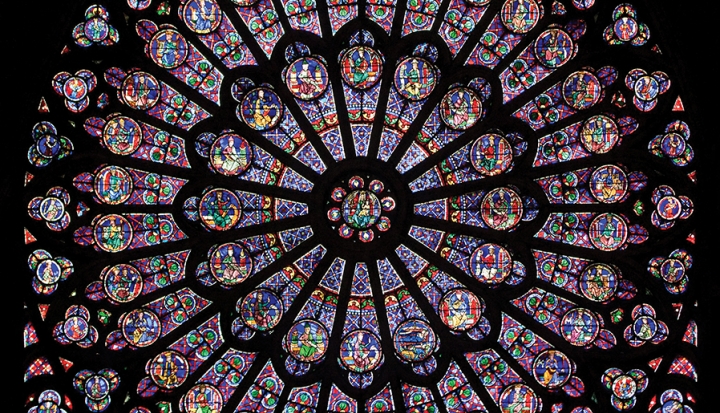

For me, acknowledging the ambiguity does not diminish the experience of the transcendent. Instead it ties it to the ever-changing, ever-similar concrete human reality of the people who pass through the cathedral’s doors to pray and contemplate the divine. Consider, for example, the rose window: a massive, intricate mixture of colors and shapes all forming a singular circle. For its creators the rose window was not just art but a symbol of mathematical perfection. The circle is a shape with no beginning and no end, intended to draw our imagination into contemplating the perfection of God. This paradigmatic medieval symbol of God’s transcendence is also a vehicle for contemplating our humanity and the immanence of God.

The circle is the shape we often use to situate our network of human relationships—our circle of friends. In describing solidarity and the call to be one human family, Jesuit Father Greg Boyle asks us to “imagine a circle of kinship and now imagine no one is outside of that circle.” Reflecting on the rose window with its intricate unity in diversity leads me to the immanence of God in the incarnation and today, to the vulnerability of migrants so often left out of that circle.

As Christians, we are called to live lives of discipleship and to more fully be the people of God in the world. In Lumen Gentium (The Dogmatic Constitution on the Church), the unity of the people of God does not have borders. Can we imagine a world in which no one is left out of our circle of concern? Borderland faith communities are living out this vision of kinship and discipleship every day. In dynamic communities like El Paso, Texas and Juárez, Mexico, families and faith communities struggle against borders that exclude people from the circle. Bishop Mark J. Seitz and the Hope Border Institute concretely demonstrated this by traveling to Guatemala to visit the families of Jakelin Caal Maquin and Felipe Gomez Alonzo, children who died in U.S. custody in El Paso.

In February I was honored to visit El Paso as part of an interfaith summit convened by Hope Border Institute and the Diocese of El Paso. The beauty of “circles” came alive in the faith and witness of people opening their sacred spaces and hearts to migrants released from government custody, often on a moment’s notice. Despite the precarious vulnerability of their situations, the migrants I met had hope in the enduring closeness of God.

As I think back to Notre-Dame and its iconic rose window, transcendence and immanence come together in its circle. For me, the circle is no longer a symbol of mathematical perfection but of Jesus’ prayer “that they may be one as we are one.” And so we are called, in humility, to see the sacred in every person, and every circle, and to be one in kinship.

This article also appears in the July 2019 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 84, No. 7, page 10).

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Add comment