After Elaine Pagels’ young son died of a rare lung disease, and later when her husband was killed in a climbing accident in the Rockies, friends would often comment that her faith must be a real help in her grief. It was. Pagels was able to find hope in the midst of Christian community, ritual, and liturgy that she didn’t experience anywhere else. But when she realized that comfort had little to do with confessing belief in any creed, she began to question how Christianity came to be associated with intellectual assent to a set of beliefs.

That wasn’t always the case, she learned. In the bestselling Beyond Belief: The Secret Gospel of Thomas (Random House, 2003), Pagels describes how early church leaders supressed another interpretation of Jesus’ message—one found in the ancient documents Pagels first popularized in her 1979 book, The Gnostic Gospels, winner of the National Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award.

The Princeton professor admits she still has more questions than answers about the origins of early Christianity and the nature of faith. But, she says,“I struggle with it because it still somehow speaks to me.”

What is the Gospel of Thomas?

Most Catholics only know of the four gospels of the New Testament. Like most people, I thought there were only four gospels. But when I went to graduate school, I learned there were all these secret gospels—the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Phillip, the Gospel of Mary, the Gospel of Peter, not to mention the Secret Book of John, the Secret Book of Paul, the Apocalypse of Paul, the Letter of Peter to Paul, the Prayer of the Apostle Paul.

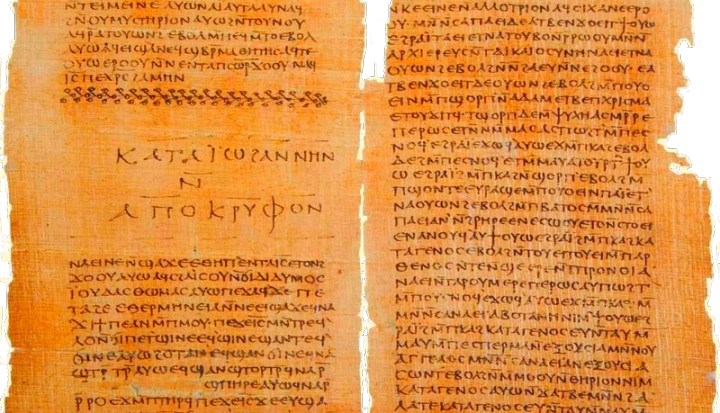

These writings, all attributed to Jesus and his disciples, were found in a cave in Egypt in 1945 by an Arab peasant digging around a cliff near the village of Nag Hammadi. He thought the 6-foot-high jar might contain buried treasure, so he smashed it. To his disappointment, it contained just some old fragments of papyrus. So he took them home. Later, his mother said she used some of them for kindling.

It turned out that what he had found was a whole library of early Christian writings, 53 in all, that came from the oldest monastery in Egypt, founded about 320. They were originally written in Greek like the New Testament, but the ones he found were in Coptic. We don’t know who actually wrote them, just as we don’t know for certain who wrote the New Testament.

When were they written?

There are scholars who say that some of these are really early gospels, written perhaps even before the narrative gospels. So if Matthew, Mark, and Luke were written in the year 60, 70, 80, or 90, Thomas might have been written in 50, only 20 years after the death of Jesus. Other scholars say they were written around 140. I think the best guess would be around 90 or 100—around the time of the Gospel of John. Both the Gospel of Thomas and the Gospel of John are interpreting Jesus after the other gospels.

Why isn’t the Gospel of Thomas in the New Testament?

In 367, the bishop of Alexandria in Egypt, Athanasius, one of the great Fathers of the church, wrote to the monasteries and said, “I know there are a lot of secret, illegitimate books that you like, get rid of all of them—except for 27.” Those 27 books would come to be called the New Testament. So the others were destroyed, except someone apparently was insubordinate to the bishop and took those texts out of the library, sealed them in a jar, and buried them to preserve them.

Why are these writings important?

First of all, they remind us that there were in the early Christian movement a lot of other writings, a lot of other kinds of Christianity that were winnowed out in the process of constructing the institutional forms of religion we today call Christianity. The Roman Empire was vast, and Christian groups were scattered all over. They were quite diverse. They weren’t uniform and simple.

We think what we have today in Christianity is a pretty wide spectrum, but it’s actually a small slice of what was available in the ancient world. If you look from Russian Orthodoxy to Pentecostalism to Mormonism, it is a lot of diversity, but still most Christians today agree on the New Testament books. This was not the case in the early church.

Don’t we believe that the Holy Spirit guided the process that led some gospels to be included in the canon of scriptures, while others weren’t?

The church teaches that the Holy Spirit guides the church into truth, so we have the right gospels. But I don’t think it’s so simple. I’m a historian, so I’m looking for human motivations, and I think you can find a few.

What’s in the Gospel of Thomas?

What does it say? It says these are the secret words that the living Jesus spoke. It claims to be, in a way, the advanced teaching. The Gospel of Mark says Jesus taught outsiders in parables and he taught some things privately to his disciples. These texts claim to offer such teaching.

The Gospel of Thomas, like the Gospel of John, says the kingdom of God is not simply an event that is going to come as a catastrophic transformation of the world. It’s a spiritual state, a way of coming to know God. The Gospel of Thomas says, “The kingdom is inside of you and outside of you. When you come to know who you are, then you will know that you are the children of the living God.” The secret of knowing who you are is not about the ordinary self, but about the part of us that comes from the divine source.

This is not a facile teaching about people being somehow divine. Rather, it’s a teaching about the image of God and how God created humans in his image. People in the first century said the image of God is a kind of light, a kind of energy. Jesus comes from the divine light and speaks about that divine source. According to this gospel, the good news is that you do, too. And it’s not just divine energy in human beings, it’s in the universe. This is a teaching some Christians didn’t like in the first century.

In your book you compare the Gospel of Thomas to the Gospel of John. How are they similar and how are they different?

Like Thomas, John assumes you know the story of Jesus. And they both say things like Jesus is the light of the world, and to understand that light you have to go back to the beginning of time.

The difference is that John says, yes, Jesus comes from the light from the beginning of time when the Word came into the world. But the good news is not that you are the light. No, you are not. Jesus is the light, and he alone.

You can begin to see that the author of the Gospel of John knew the teaching in the Gospel of Thomas and opposed it. He says Jesus is the Son of God. He is the light of the world. You and I are not. We live in darkness. We live in sin. The message is Jesus is the light, but only Jesus.

John uses a description that nobody else uses for Jesus: “only begotten son.” There’s only one son of God, and that is Jesus. John actually has almost a dialogue with Thomas. In Chapter 8 he has Jesus say, “I am from above; you are from below. I am from the light; you are from darkness.”

So John’s gospel becomes mostly about atonement and forgiveness of sins. The way to have your sins forgiven is to believe in Jesus and be baptized. You’re lost, except for this one vehicle God has graciously sent, which is the gift of his only begotten son. This has become standard Christian teaching.

So John says that Thomas is wrong. And the Fathers of the church say, “John is right. Let’s get rid of Thomas.”

What are some of the other differences in the Gospel of Thomas and other gnostic writings?

God is described not only in masculine but also in feminine terms. In the Secret Book of John, Jesus appears to John and says, “I am the one who’s with you always. I am the Father, the Mother, and the Son.”

The Gospel of Thomas says we have natural parents, but if you’re born spiritually, you’re born from the Heavenly Father and Heavenly Mother, who is the Holy Spirit who descends in baptism. But of course that didn’t make it into the Creed, and as a consequence women are excluded from positions of authority in the church.

Why did the Gospel of John view prevail over the Gospel of Thomas?

John’s gospel has a tremendous sense of group unity. In John’s gospel, there’s the idea that we are God’s people, we’re the only people who are saved. It’s very powerful language. Religious communities have always been divided over the question of inclusivity or exclusivity. Is it just our group that belongs to God, or is it everybody?

John also speaks to people who are being persecuted. It’s really strong consolidating group language. That’s why Christians in persecution have always loved the Gospel of John.

Thomas is a little diffuse. You can’t really organize a religion around this idea that everyone goes out and seeks in a deeply interior way. It speaks to a spiritual search but not to spiritual certainty. It’s not very useful if you’re trying to consolidate a church. The Gospel of Thomas is a bunch of paradoxes for spiritual study. But it’s not very useful for building an institution.

The teaching of John is a simple formula: Believe in Jesus and be saved; be baptized and join our church and you’re in. That’s not the only version of Christianity that existed or exists today. It’s a powerful kind of Christianity, and it works for a lot of people, but there are other ways to understand Jesus’ message.

But isn’t the teaching that Jesus is the only Son of God in all the gospels, not just John?

That’s what I thought, and most Christians would agree. But that just shows how the other synoptic gospels have come to be read through the eyes of John.

Yes, they say Jesus was the Son of God, but what does that mean in the first century? Most scholars say “Son of God” meant a man who’s anointed by God to rule the nations. David was the Son of God because he was the anointed king of Israel. Messiah means the anointed one. So Son of God and Messiah are names for a human being.

But all of us who grew up with Christian backgrounds think that all the gospels say Jesus is God. You do find that in John, but we came to interpret Matthew, Mark, and Luke through the lens of John, which says Jesus is God in person.

The Jesus in John doesn’t teach the Beatitudes. He doesn’t say, “Blessed are the poor.” All he says is, “I am the way. I am the vine. I am the truth. I am the Good Shepherd. I am the light of the world.” All he does in John is say, “I am.” Jesus is God. That’s the message.

Does Thomas say Jesus isn’t God?

In the Gospel of Thomas Jesus also speaks as a divine being, the same way he does in John, but the difference is he talks about that light in everyone.

It doesn’t say you are God. It says we all come from the divine source, and that source is hidden deep within us and is obscured. That’s a very different kind of teaching.

Is this Thomas the same as “Doubting Thomas,” the apostle?

Yes, although that doesn’t mean Thomas wrote it, but rather that the writer was saying, “Thomas is my teacher. This is the gospel the way Thomas taught us.”

In Matthew, Mark, and Luke, Thomas is just a name on a list, but John turns him into the one who never gets it. In Chapter 14, when Jesus says he’s departing, Thomas says, “We don’t know where you’re going. How can we know the way?” And Jesus says the famous words: “I am the way, the truth, and the light. No one comes to the Father except through me.” So get that, Thomas: except through me.

In Matthew and Luke, after Jesus’ resurrection, he appears to all the disciples except Judas Iscariot. But in John’s gospel, Thomas isn’t there. So his legitimacy as a teacher is completely undermined.

And when the apostles tell Thomas that they saw Jesus, he doesn’t believe it. Thomas is pictured as not having faith. So Jesus comes back and tells Thomas not to be faithless. In John’s Doubting Thomas story, Thomas is converted to John’s point of view.

These are really dueling gospels. They are different understandings of the teachings of Jesus at the end of the first century. But they don’t have to be antithetical. I don’t think that in the first century it was one against the other. People thought you can be baptized and have your sins forgiven, but then you can also learn what mystics teach.

A lot of this does sound like the Christian mystics.

If you look at the writings of Saint Teresa of Àvila or John of the Cross you’ll find something similar, except that they had to be very careful to say, “Wretched, miserable me!” so they wouldn’t be identifying with the divine.

The Gospel of Thomas also sounds a lot like Jewish mystical writing or kabala. The Jesus in the Gospel of Thomas also sounds a little like the Buddha when he says he has realized the divine nature in himself, and you have it within you and have to realize it, too.

What would the church look like today if Thomas were in the canon?

I don’t know. Certainly this kind of teaching can’t survive on its own because it doesn’t have an organizational basis. Perhaps it would not be so different. But I think you would have a more open-ended kind of mystical tradition, as in other religions.

Maybe it would be a little more free-ranging. It wouldn’t be that being a Christian means just signing onto a whole list of beliefs and that if you don’t believe this or that, you’re not a Christian. For example, Judaism is not so much a question of beliefs. I’m not saying beliefs are not necessary or useful, just that they by themselves don’t make a person a Christian.

If you were pope, would you re-open the issue of the canon?

I haven’t thought about that because I’ve never been offered that position. But the question is whether you just change everything about your past or whether you look at it and say, “This is the way it was done then. Do we accept that now, or do we live in a different world and look at this issue differently?”

I actually think Thomas would be a wonderful contribution. It would have been a much more open canon with that included.

But isn’t the Gospel of Thomas heresy? Doesn’t it undermine traditional Christian beliefs?

I did this research because I wanted to understand how the Creed got put together in the fourth century. That happened for lots of important structural reasons that had to do with the organization of the church after the emperor was converted. The emperor wanted a single church with everybody saying the same thing. He couldn’t have all these different groups fighting with each other, saying, “My apostle is better than your apostle.”

He wanted to define: What does a Christian really believe? So he said, let’s just sit down and hammer all this out. He invited all the bishops together at a town on the Turkish coast called Nicaea and he wined and dined them and said, “I want you to make a statement everyone can agree on.” They didn’t all agree, but the ones who didn’t left, and the ones who stayed formed what became the legitimate “holy catholic and apostolic church.”

I really love this church. But is it necessary to believe everything in the Creed? There was Christianity for over 300 years before there was a formal Creed. So that is not what makes or breaks this tradition.

I’m trying to say there are things beyond belief. Being a Christian involves a lot more than just an intellectual exercise of agreeing to a set of propositions.

Faith is a matter of committing yourself to what you love, what you hope. It’s the story of Jesus, which is a story of divinely given hope after complete despair. It’s a set of shared values by a community who believes that God loves the human race and wants us to love one another. There’s common worship, and there is baptism and communion.

Much of this is very mysterious. It’s much deeper than a set of beliefs to which we simply say yes or no.

Isn’t there a danger in picking and choosing what you believe?

Yes, I think there is. One question is: How do you know what is true, versus what is delusion and self-serving and false? That’s a very hard question, and there’s no easy answer.

That is the question orthodoxy is designed to solve, but it doesn’t solve it very well. We can hand it over to someone else and say, “You tell me what’s right,” and make Christianity a whole set of answers to learn. But this whole attitude that Christianity is somehow baby-feeding spiritual truth from somebody who has it all and you have none, that’s not very convincing in the 21st century.

People’s religious needs are different. Some people are more comfortable with a clear set of beliefs, and that’s fine with me. But I do think there are ways of relating to this tradition, loving it, and participating in it, that are different from that. A lot of people want to be told what to believe in. They feel reassured by it. I have no quarrel with that, unless they’re doing terrible things to other people.

I’m not against belief, but I do think one has to get beyond that as if it were the litmus test for what’s a Christian. Doing this work has allowed me to love the tradition without having to swallow it whole.

This article was originally published in the September 2003 issue of U.S. Catholic.

Add comment