“Any major new technology will create a lacuna in social and ethical thought in direct proportion to its novelty,” writes philosopher Bernard Rollin in his book Science and Ethics.

Any new technology raises ethical questions about how to use it.

Artificial intelligence, editing the human genome, and geoengineering: Scientists are developing new technologies at a pace never before seen. But each technology added to humanity’s scientific toolbox comes with positive and negative effects. The GPS systems used every day to find a new restaurant or go to a friend’s house are based on the same technology developed by the military after World War II to improve the nation’s warfare capabilities. 3D printing has revolutionized the way architects, engineers, and artists create their work while, at the same time, raising serious concerns about the possibility of untraceable 3D-printed guns.

The way technology is used—whether it is testing our genes for future disease or reengineering our world’s climate—is arguably as important as the technology itself. And these ethical questions are important not just for scientists and policymakers to consider but also for religious communities and individuals. To get started, we reviewed five emerging technologies and their ethical implications.

Genome editing

Scientists have discovered a way to bring bread back to the diets of the gluten-intolerant. Celiac disease is an autoimmune disorder affecting about 3 million Americans. After a person with this disease eats gluten, a naturally occuring protein in wheat, the body attacks itself, causing damage to the small intestine. People with celiac disease cannot eat food such as bread, beer, and pasta made from wheat but instead must find alternatives, such as breads made from rice or potato flour.

Thanks to a new technology called CRISPR (which stands for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats), scientists have created a type of wheat that contains far less gluten than what occurs in nature. Soon they may be able to create wheat with no gluten at all, allowing people with celiac disease to consume wheat.

The technology

While genome editing has been around for a while, CRISPR makes modifying DNA much faster, cheaper, and more accurate than ever before.

The technology comes from the natural defense systems of bacteria. When a virus invades a bacteria, the bacteria captures little snippets of the virus DNA in order to remember how to defend itself in the future. Scientists figured out how to use the process to target specific sequences of DNA in the lab, such as specific genetic mutations in animals. CRISPR can then be used to permanently change an animal’s DNA by cutting out the mutation and replacing it with a more desirable gene.

Today scientists are researching how to use CRISPR to treat genetic diseases such as muscular dystrophy, cystic fibrosis, cataracts, heart disease, and various cancers. One lab is even studying how to modify the genomes of mosquitos in order to stop malaria.

How it affects you

Genetically engineered food is well on its way to showing up on supermarket shelves. While this may help people with restricted diets, such as those with celiac disease, editing plants also runs the risk of decreasing natural plant diversity; a genetically strengthened strain of a plant could overrun naturally occurring ones.

While the technology can be used to make people, and eventually populations, immune to certain diseases, it can also permanently change the human genome. Scientists are concerned that editing a genome could cause unwanted or mistaken changes, which cannot be reversed. Because of this, most research has been in the lab. Clinical trials using CRISPR are still in the very beginning stages; the first trial by a U.S. company, intended to treat a blood disorder, was greenlit only in September 2018.

Questions from the pews

CRISPR’s potential to treat disabilities raises questions about how we define disability, says Marnie Gelbart, director of programs at the Personal Genetics Education Project. Her organization, housed at Harvard Medical School, holds discussions on genetics with community members, faith leaders, research experts, and policymakers.

What if, for example, CRISPR could be used to eradicate Down syndrome? Many parents might choose to do so, despite the fact that people with Down syndrome can live long, happy, healthy lives without feeling that they are disabled. This redefinition of disability also questions God’s creation: If all humans are created in God’s likeness, should we have the power to alter the diversity of ways in which creation presents instelf?

While this kind of technology is far from being widely available, it raises questions for Catholics about whether, given the opportunity, humans should force our personal ideas of what is right or good about creation ahead of God’s.

Geoengineering

In the mid-19th century the city of Chicago was its own worst enemy. Diseases such as typhoid and cholera were rampant because the city’s waste ran into the Chicago River and Lake Michigan, which provided the city’s drinking water. Engineer Ellis Sylvester Chesbrough devised an ambitious plan to reverse the direction of the river so that the waste flowed south: to the Mississippi River instead of into the lake. The project took years and cost the city millions of dollars, but the city felt the positive public health impacts almost immediately. The downside, however, was that many of the diseases affecting the city were carried downstream to downstate Illinois and St. Louis.

The technology

Geoengineering presents a solution to some of our most pressing environmental problems. For example, engineers are developing technologies in hopes of reversing the dangerous pace of global warming. These large-scale interventions include reflecting solar energy back to the sun before it reaches Earth and capturing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere then storing it somewhere such as in the soil. With advances in technology, these ideas have gone from fringe to mainstream in the past few years.

How it affects you

Sixteen of the hottest years on record have occurred since 2000. Climate change affects everyone on the planet. According to the Universal Ecological Fund, economic losses and health damages from climate change will cost the United States $360 billion a year, about half of the country’s expected economic growth.

Large-scale interventions could also promote complacency and move focus away from the root of the problem, says Celia Deane-Drummond, theology professor at the University of Notre Dame in South Bend, Indiana. Having the ability to reverse climate trends reduces the pressure on companies to decrease harmful emissions. People do not need to change their habits if technology can fix the effects.

“The only reason we are in the situation we are in is because of a lack of constraint in consumption,” Deane-Drummond says. “But getting back to the root of the problem, a broken relationship with God, each other, and the earth, may be the first step that needs to be made, rather than seeking solace in technological fixes.”

Questions from the pews

There is little discussion about climate engineering in a religious context, says Laura Hartman, assistant professor of environmental studies at the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh.

While intentionally altering the earth’s climate feels like “playing God,” Hartman says, we’ve been doing this already without realizing it. By damaging the ozone layer and releasing carbon emissions, humans have been changing the world for decades. “We were in fact playing God,” she says. “We were in fact altering the climate.”

Hartman says that a more troubling ethical question is who will benefit from these projects: Who will make money, and how will that money be distributed? While many of these ideas aren’t actually that expensive, if greenlit they will lead to hugely profitable patents and contracts. Historically, developing countries have been left out of climate change talks and could likely be left out of current decisions or, at least, contract negotiations. And, as with reversing the Chicago River, there will be people adversely affected by geoengineering decisions. There will be people whose voices may not be heard.

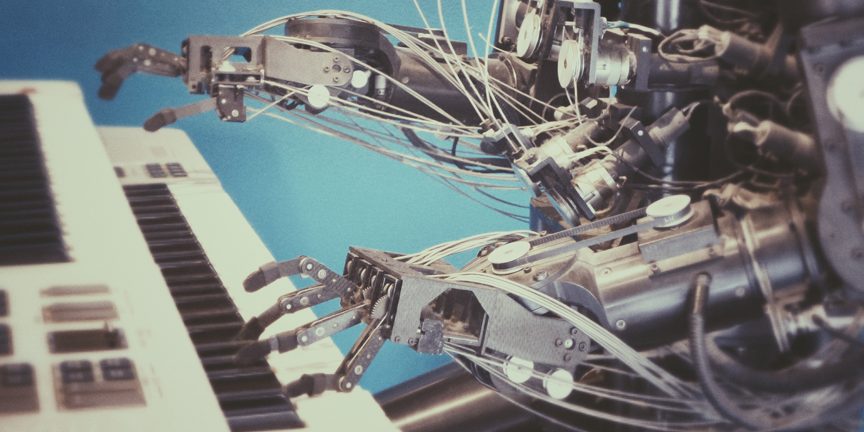

Artificial intelligence

In 2016 doctors diagnosed a 60-year-old Japanese woman with acute myeloid leukemia. However, none of the treatments they gave her worked, and her health continued to decline.

So the medical professionals turned to IBM’s Watson, an artificial intelligence (AI) system, which was able to compare the woman’s genetic information to 20 million cancer studies in 10 minutes. The results saved the woman’s life: The doctors had misdiagnosed her cancer, and she was actually suffering from a much rarer form of leukemia. Watson could do in minutes what would have taken doctors years.

The technology

One study by computer software developer and marketer Hubspot found that 63 percent of people use artificial intelligence without realizing it. From the time you wake to the end of the day, you are surrounded by artificial intelligence. You ask your smart speaker in your home to play your favorite tunes. Siri helps schedule a meeting or gives you reminders. Google monitors the morning traffic, giving you the best route to work. These are all forms of artificial intelligence.

How it affects you

Driverless cars will make travel safer. Digital assistants make vast amounts of information more accessible and can locate the right pieces at a fraction of the speed it would take a human. Algorithms solve complex math problems. The technology could benefit millions of people with disabilities.

But there are also real economic changes caused by AI. Customer service representatives have been outsourced to chatbots that can answer your questions. According to the McKinsey Global Institute, up to 73 million jobs could be destroyed by automation by 2030. Around the world, as many as 375 million people may have to switch occupations.

AI also affects our personal lives. The 2013 movie Her, featuring Joaquin Phoenix, imagines a future in which a man falls in love with a computer after a messy divorce. Parents are concerned their children’s interactions with Siri and Alexa are teaching poor manners—machines do not require “please” and “thank you,” and humans should not be treated like machines.

Questions from the pews

Mark Bourgeois of Notre Dame says our focus on recent advancements in AI and its possible uses takes us further from the root of the problem. Instead he says, “Morally, what we need to be concerned with is not [AI’s] personhood but our own. How does using and interacting with such tools change us?”

AI is blurring the line between human interactions and machine interactions, Bourgeois says. In 2011 Watson, the same computer system that correctly diagnosed the Japanese woman with cancer, beat long-time champions on Jeopardy! People look to Siri for news, weather, jokes, and stories, knowledge that in the past was usually shared through human interaction.

Bourgeois also says that Catholic social teaching can help us navigate AI: “We are called upon to relate to each other fully as persons, to value our community and to consider the common good in the choices we make.” Being able to create technology to replace human interaction is an attack on the dignity of others. Catholic social teaching reminds followers that people are more precious than objects. If creators can design systems and machines to do whatever they please, they are rejecting the inherent value of others and the benefits of being within a diverse community.

Genetic testing and privacy

The Golden State Killer was tied to 12 murders and 50 rapes in the 1970s and ’80s in California, yet law enforcement could never identify him, and for three decades he remained at large. In 2018, genetic testing identified Joseph James DeAngelo as the murderer.

Police used DNA evidence collected from previous investigations and compared it to a public online genetic database used to create family trees. From here, they were able to create a list of the killer’s DNA relatives, and eventually narrowed down the list to one: DeAngelo. Their theory was confirmed when police took a DNA sample from his home.

The technology

Researchers have been able to use individuals’ DNA to identify diseases since the 1950s, and tests to determine someone’s genetic family members have been around since the 1960s. Before the early 2000s though, these kinds of tests were primarily used in research and clinical settings.

It wasn’t until the rise of third-party genetic testing services, such as 23andMe, that this technology and its results were brought directly to consumers. These services use a saliva sample to provide consumers with information on their ancestry and potential genetic health risks. And the services are popular. Direct-to-consumer genetic testing is expected to grow from around $100 million a year to $340 million by 2022. Genetic testing companies also sell this collected data to other companies.

How it affects you

The police work brought a killer to justice, but what does it mean for your genetic data?

Human genomes can quickly be decoded to identify a person’s identity, as seen in the Golden State Killer case. But if this genetic information is leaked into the public domain, insurance companies and medical providers, for example, could use genetic information to discriminate based on preexisting or possible conditions, says Alexandre Martins, professor of theology at Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. While it is illegal for insurance companies to raise rates or deny coverage based on genetic testing results, these protections do not cover life, disability, or long-term care insurance.

The tests are not cheap, either. While some genetic tests can cost $100, others rise to several thousand dollars, which Martins says creates the potential for further inequality. Groups of people will be able to access this technology and select ways to avoid any genetic disorders. Meanwhile other groups will not have the means to take the tests or make any changes, leaving them more vulnerable to disease and with fewer socioeconomic opportunities.

Questions from the pews

Genetic testing raises questions about what Catholics are to do with the knowledge that science provides. There are no clear answers, Martins says, but the public must approach this topic with prudence and humility: prudence to ask ourselves what kinds of information we want to know and humility to determine with whom to share the information.

Genetic testing can help people prepare to face a disease or even make lifestyle changes to decrease their likelihood of developing a disorder. At the same time, these kinds of predictive tests are available for expectant parents. Once a genetic disorder is identified in an unborn child, there is little parents can do to prevent it, Martins says.

“This can create a scenery of terror in which the choice is between continuing or interrupting the pregnancy because a particular family does not want a child with any disability or such genetic probability to develop certain disease,” he says.

Such testing is already available for Down syndrome. But who are we to question or change God’s creation?

Inequalities in research

Henrietta Lacks was born in rural Virginia in 1920. By 1941 the tobacco farmer was married and moved to Baltimore, where she was diagnosed with cervical cancer.

Less than eight months later, Lacks passed away. But two tissue samples taken from her during her treatment at Johns Hopkins continue her legacy. Unlike other cells prepared for laboratory research, Lacks’ cells did not die. Instead, they continued to multiply, allowing scientists to conduct research on human cells in a way that was previously impossible. These cells (referred to as HeLa cells) led to the polio vaccine and have been used to research cancer and HIV/AIDS.

Henrietta Lacks never consented to this use of her cells. The cancer cells were taken without her permission. As Clarence Spignor, University of Washington professor of health services, says, Lacks’ life “is a cautionary tale that reflects the inherent contradiction between the stated purpose of medical research to provide benefit to humankind and the reality of blatant profiteering in the name of the advancement of science.”

The problem

Lacks’ story is only one example of inequalities between who sacrifices and who benefits from scientific research. For example, many research studies do not include women, and this lack of representation can cause adverse outcomes. Women process the sleeping pill Ambien at a rate slower than men, but the recommendations for consumption are written for men because women did not participate in the clinical trials. More than 2 million women experienced negative effects from taking drugs between 2004 and 2013, while just 1.3 million men had problems.

Minorities are also less likely to participate in research, according to the National Institute of Minority Health. This bias continues health disparities: A lack of representation for any group means they will not receive the benefits of improved health care and health outcomes. Instead, those benefits go to the groups that are studied—predominantly white men.

How it affects you

Stories such as that of Henrietta Lacks raise the question of who benefits from scientific research. The ability to grow, divide, and sell human tissue for research became a multibillion dollar industry, thanks to HeLa cells. Meanwhile, one of Lacks’ sons was homeless in Baltimore. The Lacks family never received money from the profits of their relative’s cells. While the Lacks family was eventually given some control over how Henrietta’s cells are used, the public continues to reap the benefits of these experiments.

According to Spignor, Henrietta Lacks is part of a broader trend of ignoring unethical research methods. For example, results from Nazi concentration camp experiments have been used and cited by scientists, despite the fact that the participants never consented and many were killed as a result of the tests. “Unlike the legal point of information or evidence not being admitted into a court if tainted, the fruits of unethical research is used,” he says.

Questions from the pews

Who participates in medical research and how those people are treated in the name of scientific advancement raises questions about the role of human dignity versus the advancement of knowledge. Catholic social teaching underlines the importance of placing the poor and vulnerable first, instead of using them as a means to an end. “I do not know what people can do except to read, read, read and seek out information from as many sources as possible,” Spignor says.

While tissue sharing and testing is not inherently bad, the work requires mindfulness. Rebecca Skloot, author of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (Crown Publishing Group), told Smithsonian magazine that scientists should recognize cells are not inanimate objects. “One of the lessons is that there are human beings behind every biological sample used in the laboratory,” she said.

This article also appears in the January 2019 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 84, No. 1, pages 12–18).

Top image: Flickr cc via Berkshire Community College Bioscience Image Library. Genome editing image Flickr cc via QIAGEN. All other images on Unsplash.

Add comment