“From now on, everyone stands on his own feet. . . . The time for relying on structures has disappeared. They are good and they should help us, and we should do the best we can with them. But they may be taken away, and if everything is taken away, what do you do next?”

Fifty years since Thomas Merton died, and during this year, as tumultuous and violent as any since he died, we are face to face with the reality that Merton set before us only moments before he disappeared from view: “The time for relying on structures has disappeared.”

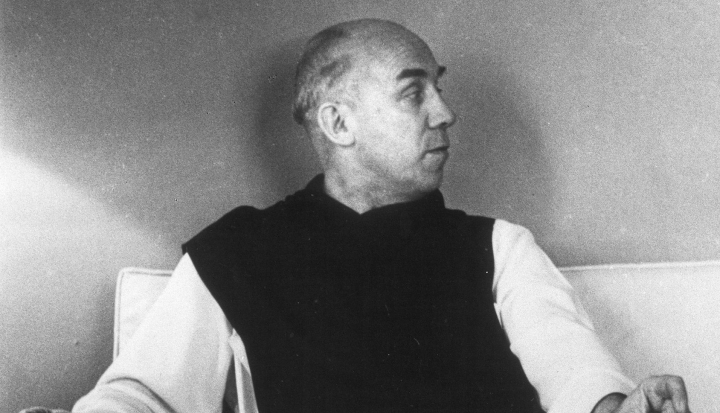

Thomas Merton was born in France on January 31, 1915. After a dissolute youth in Britain and New York, Merton professed as a Cistercian monk in the Abbey of Gethsemani of Kentucky in 1941. Seven years later, he published The Seven Storey Mountain, an autobiographical account of his conversion and one of the most important books of the 20th century. It has remained in print for seventy years.

A poet, artist, and social critic as well as a spiritual writer Merton’s retreat into Trappist silence made him a global figure during the 1950s and 1960s. While at a conference in Bangkok, Merton was accidentally electrocuted and died on December 10, 1968.

Merton died shortly after offering remarks on Marxism and monasticism. While noting some similarities between them, Merton observed that the important difference between Marxism and monasticism is found in their relationships to the world. Marxism is concerned with the structures of worldly existence, most of all with economics. The Marxist believes that we can transform human life if we transform those structures. The Christian knows that real transformation is found in metanoia, change of heart. Christianity teaches us to be concerned about worldly structures because they are directly connected to our effective care for others. When we care for the hopeless, the sick, and the poor, we must talk about economics and politics, all sorts of structures in our world. But our conversion does not come from a structure. Our hearts are changed by grace.

In his Bangkok remarks, Merton related a story told by the Dalai Lama about two Buddhist monks amid Chinese persecution in Tibet. One monk wrote to the other for advice. The reply said, “From now on, Brother, everyone stands on his own feet.” The structures that supported their monasticism were gone. Now each monk is totally responsible for himself, with no help from a monastic tradition while yet bearing the total duty of the monastic commitment.

The point is important and frightening. It also is a point that comes from the deepest reaches of our Christian faith in grace: All worldly structures are transient. All of them. And, as those Buddhist monks learned, the structures on which we rely may vanish suddenly. What remains when we find ourselves alone, when the structures fail?

Merton’s implication is plain. Christianity is not found in a structure. Christianity is found in the loving heart of each believer who is moved by love of God and love of neighbor to live a life of intimate friendship with God and with all that God has created. We should say (as Merton did say) that this is not some variety of Pelagianism. The church is not like other structures in the world, and it does not depend on us. But the church is a structure.

Since the Pennsylvania grand jury report, the revelations about Theodore McCarrick, and the “testimonies” of Archbishop Carlo Mario Viganò, the anger everywhere in the church that we must experience all of this again, because the bishops did not take the necessary steps in 2002, is palpable. The structure of the visible church in the world looks shakier than it has looked for at least five centuries. And for Americans, as the ending of 2018 finds us so bitterly encamped against one another amid a rising tide of political violence, there also are reasons to worry that other familiar structures are at risk.

What can we do?

These questions persuade me that this anniversary of Merton’s death is a moment of grace. It is an opportunity to hear a message about how to live as Christian believers, nurtured in the silence of Merton’s monastic heart. The message was timely in 1968, and it is even timelier today. As structures fail us, how can we know what we should do? What and whom should we trust?

I am reminded of a reflection Merton wrote about Advent:

Into this world, this demented inn, in which there is absolutely no room for him at all, Christ has come uninvited. But because he cannot be at home in it, because he is out of place in it, and yet he must be in it, his place is with those others for whom there is no room. His place is with those who do not belong, who are rejected by power because they are regarded as weak, those who are discredited, who are denied the status of persons, tortured, exterminated. With those for whom there is no room, Christ is present in this world.

This is such a simple idea that we forget too often in our Christian lives. Amid all the controversy and heated argument, this simplest and most essential message of Christianity can be too easy to overlook.

We put our trust in no church, or structure, or living person—not in catechism, canon law, or Catholic clergy. Finally, we put our trust in a loving God who entered our world uninvited, who found no welcome and still who desired only to be closer to us (for reasons surpassing all human understanding). We must seek always to be more like him.

Peace of Advent be with all who read these words while they struggle to keep the faith of the church in these difficult times. And, blessed be the monk of Gethsemani who struggled himself while he helped us to grasp that faith for ourselves.

Image: Flickr cc via Jim Forest

Add comment