Hi. I’m Jennon. I am a middle child, a Virgo, an INFP, an obliger. I prefer dogs to cats, blue to red, city trips to beach vacations. Once I was sorted into Gryffindor House, but the same quiz later sorted me into Ravenclaw. When in front of a newspaper, I will check my horoscope, and sometimes I’ll revisit it the next day to see if anything “came true.” I think I’d like to have my palm read, though it does make me excitedly nervous to see what might be foretold. I like good surprises and to plan for the worst case scenario.

Magazine quizzes, psychology analysis, astrological signs—to me they are fun ways to see how certain traits float to the surface and confirm the accuracy of my self-perception. These aren’t broad-stroked facts nor mystical woo-woo nonsense but something in between. When I learned about the Enneagram, a personality identifying assessment, I decided to dig deeper to learn what other label I could add to my personal toolbox. It’d be fun! I thought.

Very quickly I learned that self-discovery isn’t always fun nor easy, but it is informative.

Origin story

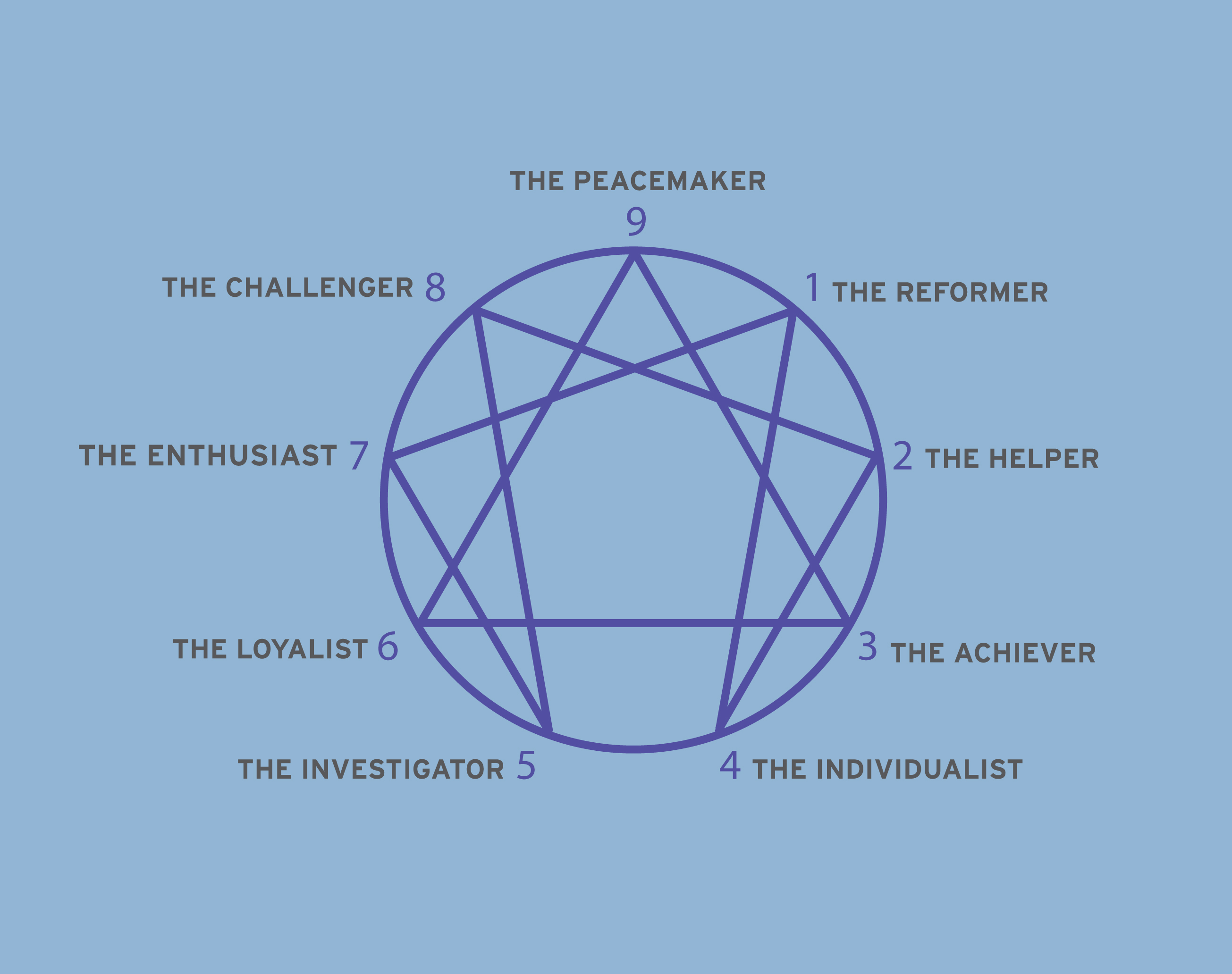

The word ennea is Greek for “nine”; gram is Greek for “picture” or “drawn”, which rudimentarily describes the nine-pointed diagram most commonly identified as the Enneagram symbol. The history of the Enneagram as we know it today has long tendrils dating back to the third and fourth centuries, when variations appeared in the Sufi traditions of Central Asia. There are also Judaic versions featured in Kabballah, echoes of it in Christian mysticism, psychological thumbprints, and Jesuit scholars bringing the ideas to their missionary destinations. The Enneagram does not have a known origination date, but it has traversed continents and centuries in its telling of the human condition.

The Enneagram first came to America’s consciousness in the 1960s with Óscar Ichazo, a Bolivian-born teacher who is recognized as the main source of the modern Enneagram for teaching self-development and personal discovery. By the 1970s and ’80s, prominent spiritual thinkers such as Don Richard Riso, Russ Hudson, Richard Rohr, Elizabeth Wagele, and Helen Palmer popularized the Enneagram with their books and schools of thought. A “self-help” wave in the 1990s helped the Enneagram find its footing in the mainstream for self-reflection and meditation—both in a spiritual sense and in a nonreligious view. Today it is a staple among many in the toolkit for introspection, discernment, therapy, and enlightenment.

For Catholics, the Enneagram is a helpful resource to cut through personal blockages that might be impeding a closer connection to their faith. Because the Enneagram illuminates both strengths and weaknesses within ourselves, it also provides a starting point or guiding hand for how to maximize our potential—for ourselves and for others. Another way to look at it: The Enneagram makes clear the talents, predilections, and gifts God bestows upon each of us.

That is, if you know how to use it.

A useful tool

Briefly, the Enneagram is a tool people use to help make sense of behaviors, actions, habits, and all other quirks and mysteries of our individual personhoods. The most common way to understand the Enneagram is to apply the nine-pointed graphic.

We are all born somewhere on the circle from one through nine. Our number represents our ingrained traits, temperaments, and dispositions. It’s our natural resting state. As we go through the world, each person must individually decide how to navigate their path to achieve basic needs. This is the classic nature versus nurture question. The point on the circle where you most closely align is your nature. How you choose to navigate your world from that starting point is the nurture.

It’s important to make the distinction that the Enneagram test is not a label-maker; we do not principally fit into our type, exclusive of the other types. Instead, the Enneagram is a map of us as a whole—each person is the entire circle, capable of behaving or reacting in any way. Sometimes it fits a pattern because it’s a developed habit, and sometimes we detract completely, thanks to free will. The point on the circle to which you most closely align is your Enneagram type; however, you can swing widely to either side or jump across to the other side as circumstances warrant. But to simply exist in the world as yourself, most people tend to follow the guidelines of a particular type and see evidence that they have always acted in accordance with the typical traits of that type their whole lives.

There are traits and abilities, strengths and weaknesses, high notes and low notes associated with each type. No one place on the circle is better or less than another—each point is equidistant to the center, and each point is equally weighted in itself. The numbers used here are not rankings but simply a labeling construct. Your type on the Enneagram is a point on the map, telling you, “In this journey called Life, you are starting from here, with these tendencies and most conditioned responses and traits. Here is the lens through which you see the world.” Studying the Enneagram further says, “Now let’s understand this lens.”

The Enneagram is a map laid over that circle, and for centuries it has proven to be uncannily accurate when describing and ascribing the personality traits of people.

What’s your type?

When I first started thinking about the Enneagram, a friend who is more familiar asked me my type. Your type is represented by a number. When I said I didn’t know, she quickly replied, “Oh, you’re a Four, for sure.” So naturally I looked up Type Four and perused the list of adjectives. Yes, I could see myself in some of the traits listed: warm, compassionate, creative, supportive. Some of the more unpleasant adjectives included guilt-ridden, stubborn, moody, and self-absorbed. I could think of instances where those applied as well.

Here, I learned my first lesson of the Enneagram process: No one can tell you your personal type. The process is based on starting from a place of open honesty with yourself and recognizing what rings truest to you. My behaviors might look like certain types to certain people at certain times, but only I can know what is authentic to me.

Of the several ways to learn your Enneagram type, the easiest is an online test. There are several available from various sources, so I picked a test that felt the least “hippy dippy” in language. My result came back as Type Two, the Helper. Again, those traits resonated: loving, adaptable, tuned into other’s feelings; martyr-like, manipulative, indirect, overly accommodating. Interesting results, but this type did not feel “right,” either.

Elyse Nakajima, director of digital presence of the Enneagram Institute and coach, assures me that my experience is quite common. “For some people, a common response is to take a test and read a description and just get all the lightning, bells, and lightbulbs right away—that the assessment is so accurate it’s creepy,” she says. “No matter how skeptical the person was to begin with, something about the Enneagram just nails it for them and they find their type right away.”

And for the others? “Then there are people who go on a journey to discover their type—try on a couple—take the test a few times, because what it’s returning is not landing, there’s no giant wake-up or a feeling like a splash of cold water on your face,” Nakajima says. I start to worry that the Enneagram won’t work for me if I can’t nail down my type. Will there ever be an “a-ha moment”?

“The Enneagram is your blind spot. It’s like a fish in water: they don’t see water, it’s just the way it is,” says Clarence Thomson, an Enneagram coach, former priest, and retired director of Credence Cassettes for the National Catholic Reporter. Thomson also holds two master’s degrees in social communication and theology and has spent the better part of his career intensively studying spirituality and humans’ understanding of ourselves, writing several books about the Enneagram, and currently giving Enneagram coaching sessions via phone. So when he tells me that “most of the tests online are very unreliable,” I feel less confused and more open to looking for a more authentic fit.

I took Thomson’s Enneagram assessment, consisted of 12 open-ended questions that sounded more like beauty pageant prompts than deep spiritual vault openers. If you were an animal, what would you be? What would you want written on your tombstone? What is your pet peeve? Some of the questions were so broad that my responses were middling and it felt unhelpful. What I learned later was that it’s not only what I answered but also how that helped Thomson figure out that I am a Type Six: The Loyalist.

While I was initially surprised and a little frustrated to be identified as another type, when Thomson and I had our follow-up call I felt more in tune with the Type Six trademarks—positive and negative: loyal, hard-working, concerned for the common good, great organizers, as well as suspicious, “worst case scenario” thinking, rigid, second-guesser. Thomson said many journalists tend to be Sixes because Sixes inherently ask a lot of questions and want to get to the root of the matter and are often unable to let up. While some aspects felt spot-on, I couldn’t help but be wary of the elements that really felt off the wall for me, personally. Thomson told me, “That’s a very Six thing to think.”

So, what if I don’t want to be a Type Six—can I change my type? The consensus from Thomson, Nakajima, and several other sources, such as Christopher Heuertz’s book The Sacred Enneagram, Richard Rohr’s site Center of Action and Contemplation, and Personality Types by Enneagram Institute founders Don Riso and Russ Hudson is: no, not really. Though people evolve and grow, learning from experiences and adjusting, our Enneagram type is a base part of our nature from birth. While it is only one point on the circle, it is the most dominant or favored point that we use to develop our worldview.

“The Enneagram tells you one important thing about you, but it doesn’t tell you all the important things,” says Thomson. “The Enneagram is your coping skill; it’s not complete, there are lots of other ways to act. It’s something you do, not an identity.”

Nakajima adds, “The Enneagram symbol is a precise map, but it’s not the spiritual work itself. You take that [type] to your practice, apply it, and it’s a powerful tool.”

So my type isn’t set in stone, and knowing that will help as I navigate life experiences in which the Enneagram will help highlight my typical patterns. Which brings up a good point: When should I use the Enneagram?

What’s the use?

We live in a social culture where we thrive on connection and relation. When our actions, or our reactions to others, do not feel centered or balanced, it bothers us, like a pebble in our shoe. Understanding the lens through which we view the world and recognizing the lens by which others operate can go a long way toward having healthy relationships—with ourselves (addiction patterns, destructive thinking, self-sabotaging, outsized or out of control emotions, etc.), with others (toxic friendships; patterns of verbal, emotional, physical abuse; parental relationships; coping mechanisms), and with the universal community (understanding others’ politics, values, beliefs, behaviors). Ways in which to apply the Enneagram are limitless.

Self-reflection is the most common, as it’s the starting point for optimizing personal potential and happiness. While there are many books and countless online resources (many already named above), the depth and breadth of knowledge to gain by studying the Enneagram might best be done with a practiced guide, such as an Enneagram coach or spiritual director.

For Catholics, it’s akin to knowing the gospel message of Jesus but then actively figuring out how to live a modern faith-filled life in accordance with Jesus’ message. Another way to look at is: If “feed the hungry, help the poor” is the catechism, then “how can I apply the talents and strengths God has given me to be the best follower of Christ that I can be?” is the Enneagram.

Peter White is a spiritual director and United Methodist minister who uses the Enneagram when counseling individuals, married couples, and clergy. Every day, he sees practical applications of the Enneagram.

“To me, there are three spheres. The first is the personal, self-aware version: to simply be a better person. That directly spills over to relationships. The second is when someone has questions about the church that never go away,” White says. “[The Enneagram] is a really helpful tool to have empathy for others, really listen to others, to give distance to people, to see there are different options and different perspectives. Thirdly, it’s a tool to talk about what God is like and our relationship with God. How do you relate to God, particularly through your type?”

White adds, “All of humanity is made in the image of God, and these nine types are reflective of what God is like. If we look through scripture, we can see different instances of God looking like each type.”

For these reasons, it’s not surprising that some religious communities have moved toward the Enneagram to help discern the most mysterious of relationships: the one with Jesus. However, some are wary of what the Enneagram represents and think it can be used a false tool for finding communion with God.

For example, in 2003 the Pontifical Council for Culture and Interreligious Dialogue published “Jesus Christ the Bearer of the Water of Life,” in which it warned against the dangers of New Age practices: “Gnosticism . . . has always existed side by side with Christianity, sometimes taking the shape of a philosophical movement, but more often assuming the characteristics of a religion or a para-religion in distinct, if not declared, conflict with all that is essentially Christian. . . . An example of this can be seen in the [E]nneagram, the nine-type tool for character analysis, which when used as a means of spiritual growth introduces an ambiguity in the doctrine and the life of the Christian faith.”

While some in church leadership might be wary of its origins, people are flocking to the Enneagram as an entry point to their relationship with God. White notes, “In the scriptures, the first question God asks is ‘Where are you?’ after Adam and Eve take what they aren’t supposed to take. It speaks to our human condition, our human dilemma. The Enneagram gives us a framework, a way to say, ‘This is where I am, this is how to move forward.’ ”

Speaking to that is a quote I found in Heuertz’s book, The Sacred Enneagram (HarperCollins): “The mark of spiritual growth is when we stop polishing the mask and instead start working on our character.”

Building and fostering quality character is an aspiration beyond spiritual seekers. In fact, corporations are adopting the Enneagram in order to better address office issues, such as communication styles, leadership effectiveness, and how to maximize employees’ strengths and mitigate weaknesses.

“For businesses, psychometric tests are in. Everything from one-off coaches and major global firms who use things like StrengthsFinder, Myers-Briggs, etc., are interested in finding the right application for the Enneagram,” Nakajima says. “Many HR departments or C-suites use it for executive coaching leadership or as part of the on-boarding package [for new employees].” She also notes that the Enneagram Institute often works with a range of industries, from academia and research to health care and therapy. “Once people get into it, they see potential applications everywhere.”

While Thomson, Nakajima, White, and nearly every book I researched cautioned against “typing” another person, Thomson concedes by saying that “Once you know someone’s type, how do you ‘unknow’ it?” Meaning that relating internally to another person through their type is different than labeling them anything specific. I was reminded time and again that there is no right or wrong type.

“I don’t see [typing someone] as a danger,” Becca Russo says, “because it’s not the Scarlet Letter to be any one type. I think that knowing a person’s Enneagram type is having a basic—but not complete—idea of their gifts, and it gives you more understanding of the person.”

This is helpful in the dating scene, when making an authentic and genuine connection in the digital age can feel exhausting. As Millennial urban professionals, Russo and Rosemary Lane find the personality tool to be helpful in their professional and personal lives. They say that knowing a date’s Enneagram type is a fun way to get to know someone, as long as you don’t put too much emphasis on the result. And it’s definitely a more interesting conversation than talking about their job or the weather.

It was in that spirit that I took one last test, the most popular version that has been independently scientifically validated. Developed by Don Riso and Russ Hudson, the cofounders of the Enneagram Institute, the Riso-Hudson Enneagram Type Indicator (RHETI v2.5) is 144 paired statements that promises not just your basic type but also a full personality profile across all nine types. I was ready!

When my results came back as a three-way tie (!!!) it was frustratingly comical, but Nakajima reminded me of a core truth: “The best way to find harmony is understanding and acknowledging the wholeness of ourselves.” I’m not one type, I’m one person of many types, and the three most dominant are Type Six, Eight, and Two. Nakajima pointed me to resources about type misidentification but also offered a daily exercise I can do that might help me fully see my actions as they are in real-time.

“Get really curious about how these patterns are playing out—not how we think they should be or what we want them to be but how it actually is,” Nakajima says.

My frustration gave way to curiosity. The more I dig into the Enneagram, the more I can see that it is what you make of it. Knowing your type is just the start of a conversation with yourself, and it can go as deep and as lengthy as needed. The danger is that you may flail without guidance, over-type yourself, or get so into how much you fit the type that you forget that it’s a baseline, not an edict.

The reality of a tool like the Enneagram—and to be clear, it’s a tool, not a religion—is that there’s always more to uncover. I just have to seek it.

This article also appears in the December 2018 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 83, No. 12, pages 12–17).

Image: Ben Mullins on Unsplash

Add comment