Religious communities of men and women have been woven into the fabric of America since its very beginnings. Working in parishes, schools, hospitals, orphanages, social services, and much more, these men and women religious have shaped not only Catholic history but American history as well.

Sister Celsa Heider, O.S.B. taught in Melrose, Minnesota from 1898 to 1965. Except for two of those years, she taught first grade to 2,500 youngsters from three generations. Courtesy of St. Benedict’s Monastery Archives, St. Joseph, Minnesota.

Due to cultural changes and a decreased interest in religious life, today many of these communities have shrunk in membership or even closed. The Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA) reported in 2014 that the total number of women religious in the United States had fallen below 50,000, a 72.5 percent decline from the 1960s, when women’s religious orders were at their peak.

These communities have historically kept archives—books, letters, publications, photographs, artwork, legal documents, and other artifacts—that were “substantial and worth recording,” says Ellen Pierce, a religious archives consultant and former director of the Maryknoll USA archives. But as these communities begin to shrink and eventually close, many are left wondering: What will happen to their archives? Even more important: What will happen to the evidence of their crucial role in American Catholic history?

These archives are historical gold mines that paint a picture of American history not found anywhere else, especially when it comes to ethnic, immigrant, and working class groups. “You can’t understand the formation of the United States without understanding the Catholic population,” says Malachy McCarthy, archivist for the Claretian Missionaries USA-Canada Province. “Religious archives are one of the only places you’re going to find working class history.”

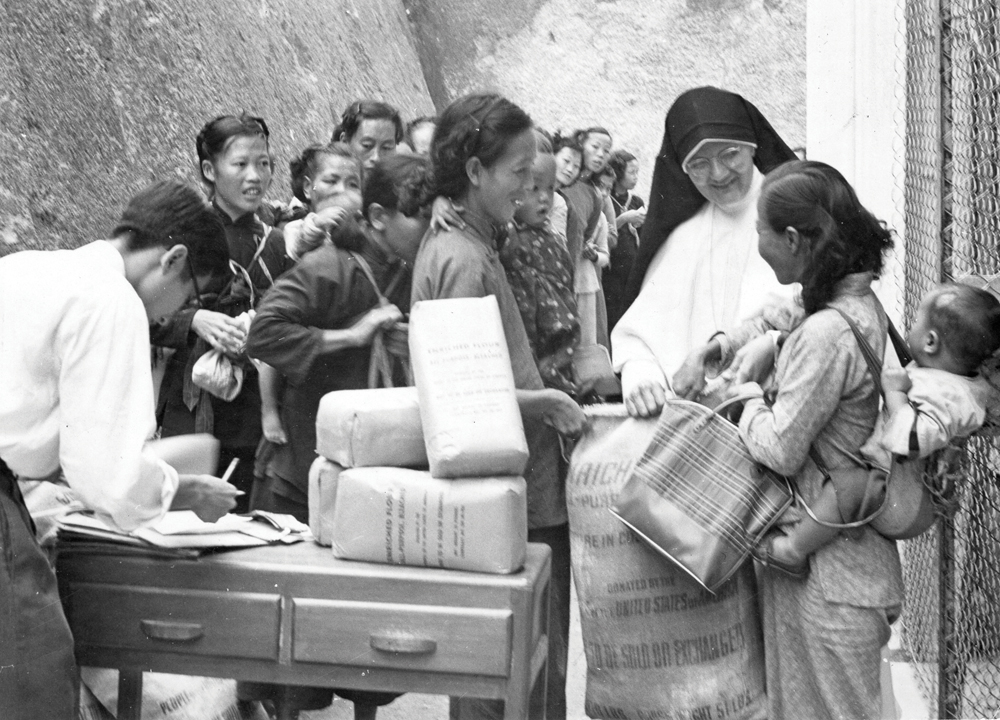

Maryknoll Sister Moira Riehl distributes rice and flour to refugees at King’s Park in Kowloon, Hong Kong in the mid-1950s. Courtesy of the Maryknoll Missions Archives.

McCarthy, along with Christian Dupont, Burns Librarian and Associate University Librarian for Special Collections at the John J. Burns Library at Boston College, organized Envisioning the Future of Catholic Religious Archives, a working conference at Boston College in July that brought together archivists, religious leaders, and historians to begin discussing how best to preserve these Catholic archives—and the important chunk of American history to which they attest.

History worth holding on to

European Catholics started to arrive en masse in the United States in the 1820s and ’30s, and by 1908 they were largest denomination in the country. As these immigrant populations arrived, religious communities of men and women welcomed and helped them begin their lives as Americans.

“The men’s communities provided pastoral leadership because they preserved the culture of their homelands,” McCarthy says. “The women’s communities provided the educational framework, charitable institutions such as orphanages, and the basis of the parochial school system.”

By the mid-1960s more than 200,000 Catholic women in more than 400 religious communities were living and working as an “invisible, and often taken for granted, workforce that had created or staffed thousands of schools and hundreds of hospitals and social service agencies across the country,” writes Carol Coburn, professor and director of the CSJ Heritage Center Department of Religious Studies and Philosophy at Avila University, on the Unmasking the Archives blog.

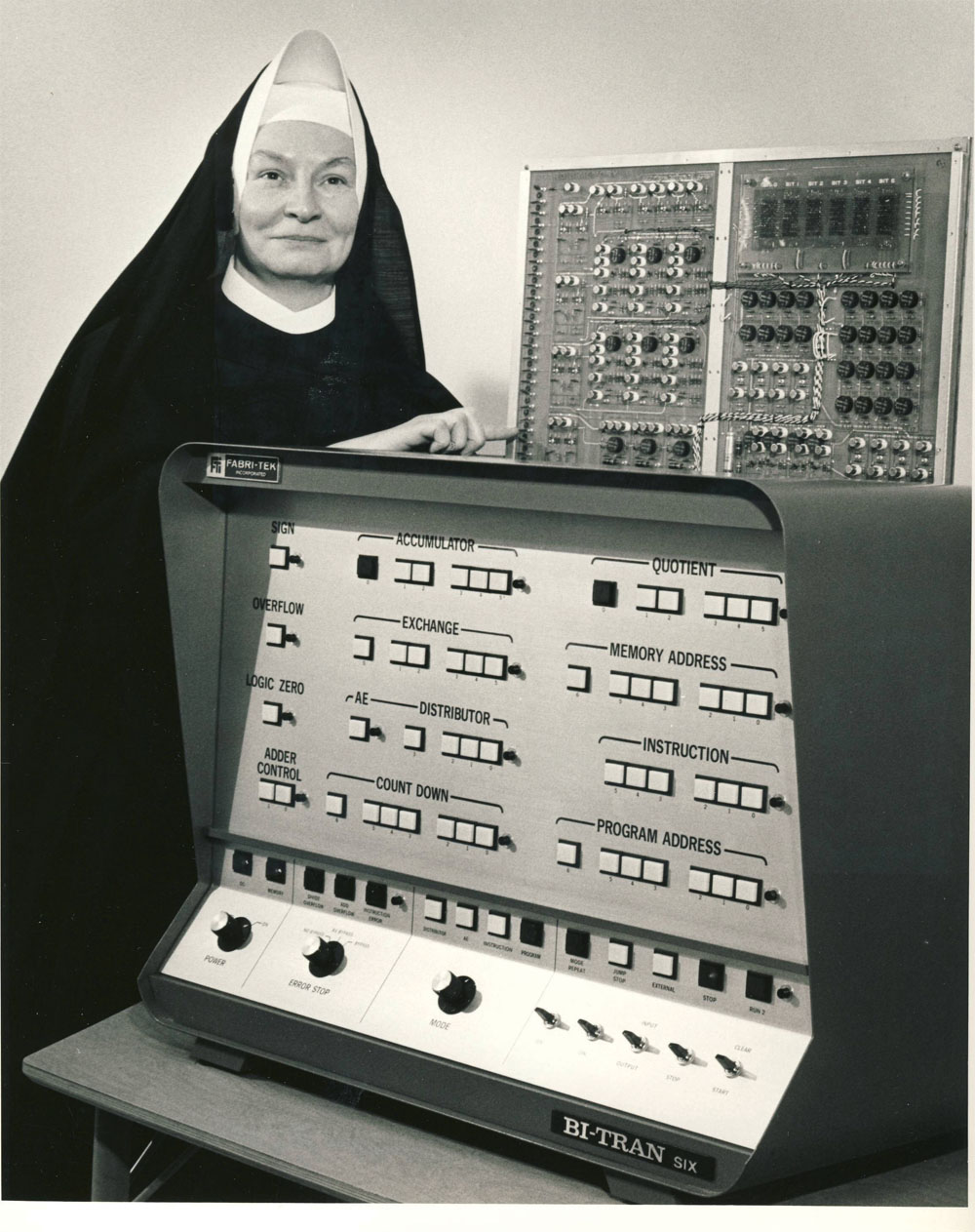

Sister Mary Kenneth Keller, B.V.M. demonstrates the Bi-Tran Six in 1965. She was among the first women to receive a Ph.D. in computer science. Keller anticipated the importance computers would have in the future, recognizing that their “function in information retrieval will make [them] the hub of tomorrow’s libraries.” Courtesy of Clarke University.

These men and women religious were physically rooted in local communities, so they held a unique vantage of the social and cultural struggles immigrant and working class populations faced. They were there to “meet the needs of every aspect of their parishioners’ lives and realize the potential of those in front of them no matter their race, color, or creed,” McCarthy says.

For example in the 1970s the Sisters of St. Joseph in Boston saw a growing population of homeless youth. To help address the needs of these kids they started Bridge Over Troubled Waters, which is still in existence today. Likewise the Sisters of Mercy in Atlanta started the St. Joseph Mobile Health Unit, which attended to the health needs of immigrant communities across Atlanta.

“It is important to remember and emphasize that the lived experience of American sisters is embedded within broader social and cultural struggles that rocked the nation in the last half century,” Coburn writes. “These contributions to social justice cannot be overestimated and provide a significant narrative in American social history, women’s history, and Catholic history in the 20th century.”

It’s only within religious collections that those narratives truly come to life, which is why preserving them is so critical. Catholics and non-Catholics alike have been “impacted by these men and women their whole lives,” says Pierce. These collections show “their history as well as the sisters’ history.”

Not only did women religious educate students by the thousands, they were also “Sister-Builders,” who financed and designed modern schools such as Mundelein College in Chicago. Courtesy of the Women & Leadership Archives of Loyola University Chicago.

An uncertain future

The conference in July at Boston College was the first time archivists, religious leaders, and historians got together to discuss the future of these Catholic religious archives. It was important to bring these groups together, as each has a unique relationship with the collections.

“Archivists themselves know the collections,” McCarthy explains, “religious leaders are responsible for their welfare and the lasting legacy of their communities, and historians are the ones who actually use these collections.”

For Pierce, who has worked with religious archives for over 30 years, getting these collections “out into the sunshine” is incredibly important. “People can see what these men and women religious were doing and connect it with American history,” she says.

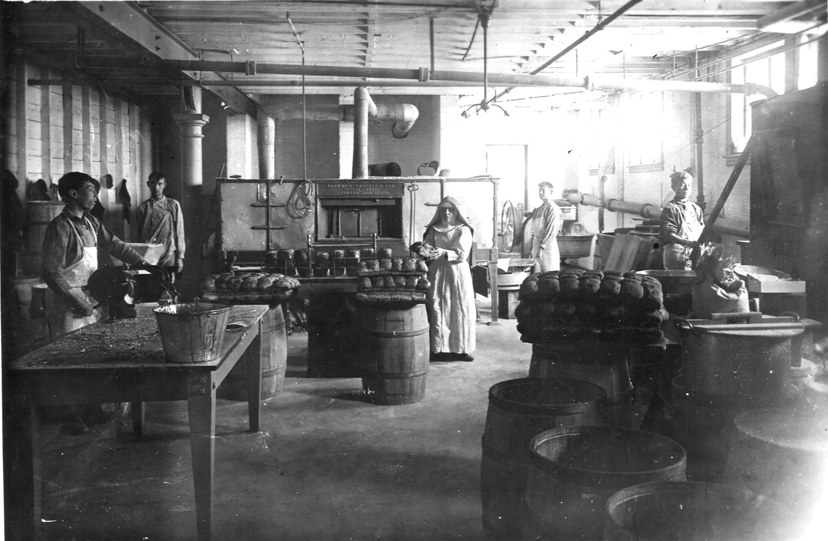

Nazareth Trade School in Farmingdale, Long Island, New York. Courtesy of the Sisters of St. Dominic of Amityville, New York.

For leaders of religious communities the uncertain fate of their archives is deeply troubling—and personal.

“Our archives are the repository of who we are, our history, who we have been,” says Benedictine Sister Lynn Marie McKenzie, president of the Benedictine Sisters of the Federation of St. Scholastica in Cullman, Alabama. “If we don’t take care of them, then we don’t really understand where we’ve come from and are probably destined to commit the same mistakes of the past.”

The archives include “stories full of risk and sacrifice. There are lots of instances of God’s providence and human ingenuity connecting along the way,” Sister Kati Hamm of the Sisters of Charity in Halifax, Nova Scotia says of her community’s collection. “As we journey into the unknown future we are doing it with courage and creativity. The story of grace working through this group of women is one worth holding on to.”

Historians have a different perspective than that of the men and women religious when it comes to maintaining these archives. The research potential within these collections is unparalleled. If located in universities or other research institutions, they would greatly enhance curricula across disciplines—from U.S. history to economics, education, women and gender studies, and more. Coburn says that it’s imperative the material be “preserved, accessible, and communicated globally in a world searching for meaning and survival in the 21st century.”

Finding a place to house and maintain these archives presents myriad logistical—and emotional—challenges. Some religious orders have begun consolidating the archives from their communities across the country into one central location. But, as Pierce points out, “there’s a psychological component to this where people don’t want to get rid of things.”

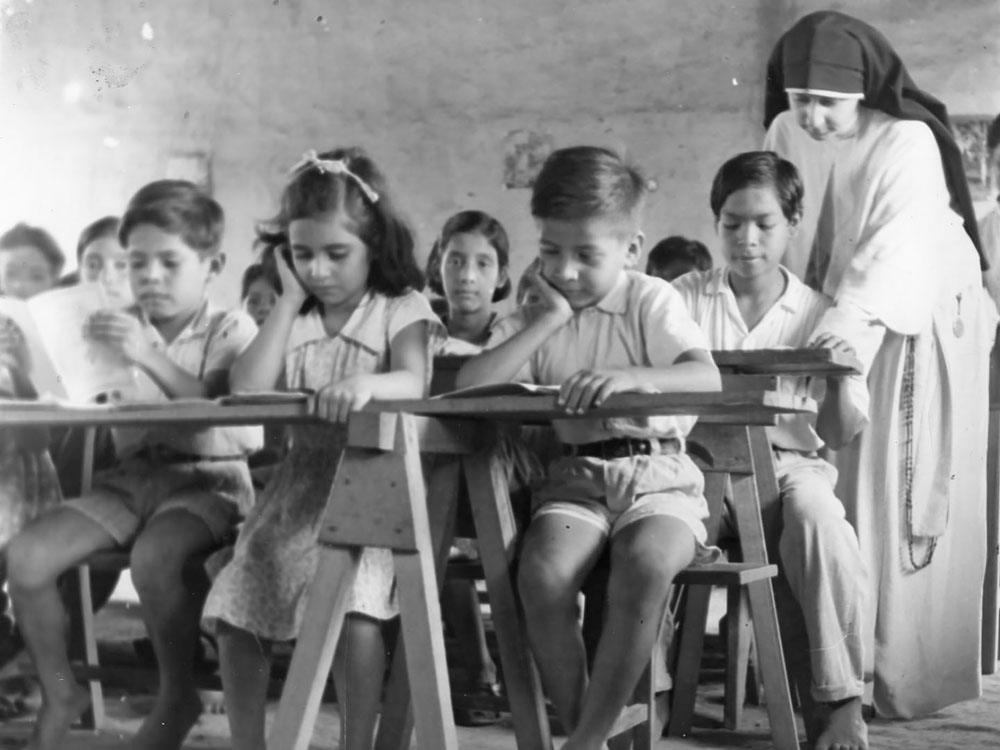

Assigned to Bolivia in 1944, Sister Joanne Connell, M.M., was one of the pioneer Maryknoll Sisters in Latin America. She was a principal and teacher at schools in Riberalta and Guyaramerin and was the foundress of Our Lady of Carmel Parish School in Riberalta. She also served for six years as principal and teacher at Santa Ana Parish School in Cochabamba. Courtesy of the Maryknoll Missions Archive.

There’s also been talk of creating regional or even national repositories where collections from different orders could be held together. That brings up questions of how to standardize the materials, hire and train personnel to maintain the collections, and maintain long-term financial sustainability.

While the future remains uncertain for the archives of dwindling religious communities, the conference was a good first step in acknowledging the severity of this issue. “The critical thing to realize is that time is not on our side,” McCarthy says. The treasure trove of information found in these archives is “foundational to who we are as Americans,” he continues. And that alone makes them worth saving.

This article also appears in the August 2018 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 83, No. 8, pages 12–17).

Header image: Alexian Brothers Hospital ambulance, ambulance drivers, and physician interns in front of Alexian Brothers Hospital in Chicago, Illinois, circa 1920. Courtesy of the Alexian Brothers Provincial Archives, Arlington, Illiniois.

Add comment