A few days after Election Day, I met with a dear friend who was struggling with unexpected anger after the election of Donald Trump. “I think of myself as a person who embraces diversity. But how diverse can I be if I hate half the people of this country?” She paused for a moment and then noted soberly, “Actually, I am beginning to understand how easy it is to dehumanize a group. All I see when I look at all those Trump supporters is a bunch of racists and bigots.”

It was a jarring statement. My friend is on the whole a very peaceful person who values pluralism and tolerance. But the run-up to the election and its aftermath were hard for her. When the neighbors put up a Trump/Pence sign, she found herself avoiding them. “I don’t like it, but I just can’t stand to be around them and the views they hold,” she told me. “They oppose everything I stand for.”

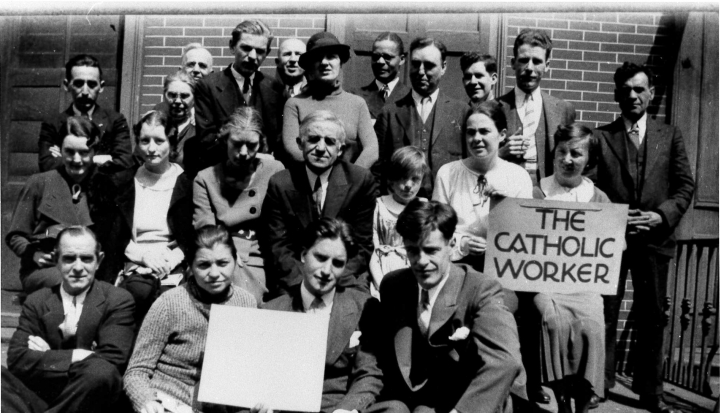

This exchange reminded me of an encounter that Dorothy Day, founder of the Catholic Worker movement, had with an explicitly anti-Semitic and racist elderly guest whose “greatest affliction was having to share the hospitality of the city with Negroes.” Despite the repugnance of his views, Day insisted that this man was still a guest and ought to be welcomed as “Christ among us” by the Catholic Workers.

It can be easy to romanticize the poor, but Day knew that those whom we are called to serve are quite frequently disagreeable and often sinful. As a spiritual practice, hospitality teaches workers to abandon any expectations they may have and resist the ever-present temptation of self-righteousness. Hospitality in its truest form is “making room” for the guest we do not choose. It requires vulnerability and a willingness to be surprised by who we find at our door.

This is particularly challenging when the guest at our door professes values, tacitly or explicitly, that are not only contrary to our own, but, as in my friend’s case, immoral. Yet Jesus ate with sinners. It is one thing to imagine a dinner with adulterers and tax collectors; it is quite another to imagine sharing a table with racists, sexists, xenophobes, and anti-Semites.

For Day, pacifism emerged from such a radical hospitality. To welcome any guest as Christ, particularly a sinner, we need to experience what she called a “disarmament of heart.” This disarmament of heart undergirded the neutrality of the Worker movement during the Spanish Civil War, despite the fact that many Catholics argued for supporting Franco as a last defense against Communism. Day insisted that her workers prayed not for the Franco supporters, nor for the Communist loyalists, but for “the Spanish people—all of them our brothers in Christ—all of them Temples of the Holy Ghost, all of them members or potential members of the Mystical Body of Christ.”

Far from “being passive,” Day’s response to violence was to act “disarmingly,” to remove any barriers that stood in the way of love. The most effective response to violence, thought Day, was a hospitality that humanized. In The Long Loneliness, she writes:

“We cannot love God unless we love each other, and to love we must know each other. We know Him in the breaking of bread, and we know each other in the breaking of bread, and we are not alone anymore.”

My friend’s comments about Trump supporters reveal how deep and visceral the divisions in our country are. The Christian tradition with its commitment to radical hospitality equips us to be a force of unity and reconciliation, but only if we are willing to adopt a sort of Catholic Worker neutrality and make room for our neighbors—in our homes and in our pews—without casting judgment or taking sides. This does not mean that we do not stand up to evil in the world, but it does mean that we refuse to fight on the world’s terms. We can begin by being attentive to opportunities to open our door and say “come in.”

This article also appears in the February 2017 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 82, No. 2, page 10).

Add comment