When I walked into the L’Arche home six years ago, I saw the reproduction of Rembrandt’s “The Return of the Prodigal Son” on the wall. L’Arche is an international, faith-based nonprofit that creates homes where people with and without intellectual disabilities share life. I was visiting the community in Washington to interview for a position as a direct care assistant. The home and its inhabitants were unfamiliar, the sight of the painting, comforting. Since I minored in art history, seeing a Rembrant was like seeing a friend.

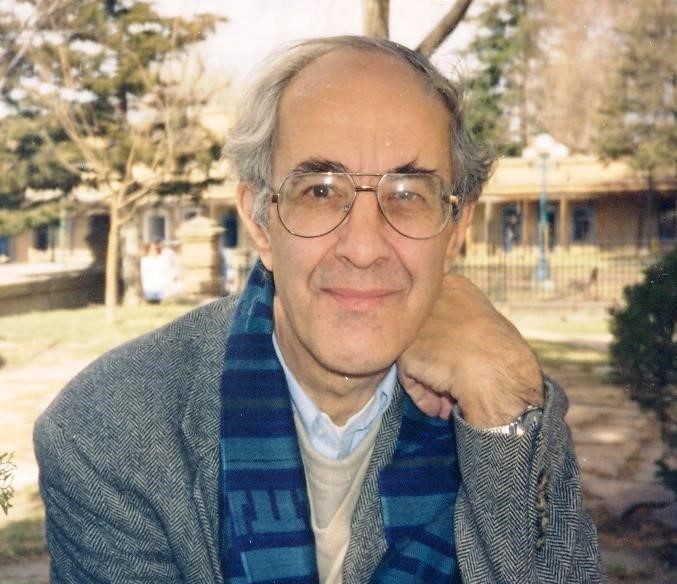

For Henri J.M. Nouwen, a Catholic priest, writer, and theologian, the Rembrandt also stirred intense emotion. While living at the original L’Arche community in Trosly, France, Nouwen encountered a poster of the painting. In his book The Return of the Prodigal Son (Image Books), Nouwen writes that the image “makes me want to cry and laugh at the same time. . . . I can’t tell you what I feel as a I look at it, but it touches me deeply.”

At the time Nouwen was vulnerable, lonely, and exhausted from a lecture tour. Yet soon after discovering the poster, he made a pilgrimage to see the original painting at the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia. After nine months with the Trosly community, he moved to L’Arche Daybreak near Toronto to serve as the community’s pastor.

When I first visited L’Arche, I was tired from travel and nervous about interviews. I wasn’t thinking about remaining long term. But after graduating from Vassar, I moved into the L’Arche home with the Rembrandt reproduction on the wall. I intended to stay one year, and ended up staying five. Nouwen remained at Daybreak for the last 10 years of his life. Something about the Prodigal Son called both of us home.

Nouwen was ordained in 1957 and he published his first book Intimacy: Pastoral Psychology Essays (Fides) in 1969. The slender volume explores the principal theme of Nouwen’s eventual legacy as a spiritual writer and teacher. This question of intimacy underlies his every text: “How can I learn to love, and to let myself be loved?”

Nouwen went on to author a total of 53 books (including posthumous volumes). His books have sold millions of copies and been translated into dozens of languages. His lasting influence is evident; his journals still inspire posthumous publications, such as the recent Discernment: Reading the Signs of Daily Life (HarperOne).

Nouwen’s writings reveal his deep sense of solitude and loneliness, even as they emphasize the importance of community and shared ministry. For those grappling with such paradoxical truths, Nouwen’s books offer a sense of solidarity in the struggle. And for those wounded by legalistic, harsh teachings, Nouwen’s relational, compassionate spirituality offers comfort.

Nouwen received the first intimations of a call to L’Arche in the late 1970s while serving as a professor of pastoral theology at Yale Divinity School. As Deirdre LaNoue recounts in The Spiritual Legacy of Henri Nouwen (Bloomsbury), a woman named Jan Risse traveled to Nouwen’s home to bring greetings from Jean Vanier, L’Arche’s founder. Nouwen was puzzled—at the time, he had met neither Risse nor Vanier—but even so, he welcomed Risse. Vanier later invited Nouwen to a retreat in Chicago, and their friendship flourished. This precipitated Nouwen’s decision to move to L’Arche Daybreak in 1986. It was a rather shocking choice, given his prominence as a top professor and national speaker.

Nouwen was introduced to L’Arche through mysterious means. For me, it was a chance encounter with an ad for L’Arche that changed my life. People didn’t understand why I would pursue L’Arche, but something within me knew that I didn’t need prestige; instead, I needed to love and be loved. Nouwen writes in similar terms in The Return of the Prodigal Son: “Moving from teaching university students to living with mentally handicapped people was, for me at least, a step toward the platform where the father embraces his kneeling son. . . . It is a place that confronts me with the fact that truly accepting love, forgiveness, and healing is often much harder than giving it.”

To be sure, accepting love at L’Arche is not a passive exercise; Nouwen himself found the tasks of community life at Daybreak difficult. In Wounded Prophet: A Portrait of Henri J.M. Nouwen (Doubleday), Michael Ford quotes a monk who worked alongside Nouwen as saying, “I had to tell him everything, even how to use a can opener.” Nouwen persevered, however. And so did I.

As we remained in community, L’Arche brought healing to wounded places. When I came to L’Arche, my relationship with my brother Willie weighed on my heart. Willie, who has autism, had been struggling with aggressive and self-injurious behavior for years. I was the elder son in the parable: compliant on the outside, resenting my brother on the inside.

Nouwen also struggled with anger at his spiritual siblings. In The Return of the Prodigal Son, he writes, “I was the elder son for sure. . . . I had been working very hard on my father’s farm, but had never fully tasted the joy of being at home. . . . I had become a very resentful person: jealous of my younger brothers and sisters who had taken so many risks and were so warmly welcomed back.”

Yet life at L’Arche proved transformative for us both. Gradually we grasped that the younger son in the parable was not so different from us after all. We came to see that we, too, ran away from home, from God, and from people. We began to glimpse the truth in what Nouwen’s close friend Sue Mosteller said: that we are meant to become like the father in Rembrandt’s painting of the parable. We are meant to become that luminous figure with face alight, hands gentle, love palpable.

Nowadays I recognize him in the eyes of my L’Arche friends, my brother, and sometimes—ever so fleetingly—in my own.

Image: Frank Hamilton, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Add comment