Though his critics persist, Óscar Romero’s martyrdom has finally been recognized.

Just before Robert White was dispatched as U.S. ambassador to El Salvador in 1980, he attended a National Security Council meeting that included a lively discussion of how much Archbishop Óscar Romero was screwing up U.S. Central American strategy. The archbishop’s “anti-American sermons, his politicizing of religion, and his incitement to rebellion” had been noted by an increasingly apprehensive Carter administration.

As White recalled in Commonweal magazine in 2010, the chief White House official present at the meeting suggested White make a brief detour to Rome to see if the Vatican could do something about this meddlesome prelate. “Not for the first time, I marveled at Washington decision-makers’ lack of understanding about the new role of the church in Latin America,” White recalled.

“I had read Romero’s sermons and, while they were certainly combative, they accurately reflected the cruel reality of a lawless country where the poor had given up hope that any moderate government would risk challenging entrenched power. All the people’s trust resided in ‘Monsignor Romero,’ who each Sunday spoke truth to power and inspired millions to believe that change was possible.”

White realized something that many in Washington did not grasp: His success in El Salvador depended on the goodwill of Romero.

Robert White passed away in January at the age of 88. Like Romero, he spent a lifetime speaking truth to power, even as he was an active participant within that power. While others stockpile hope in agitation from the streets, White believed that change can also come from within political establishments. He fought that good fight for many years before he finally spoke one hard truth too many: insisting that the Salvadoran military orchestrated the rape and murder of four American church women just eight months after Romero’s death.

Just about a week before White’s death, a panel of theologians at the Congregation for the Cause of Saints officially recognized the martyrdom of Romero—35 years after his murder on March 24, 1980. It will probably surprise the people of El Salvador, who long ago informally canonized this saint of Central America, that it took the Vatican so long to acknowledge his martyrdom. In his death, as he had been in his life, Romero was swept up in larger political and ideological forces. For decades his cause has been “blocked” in Rome and his martyrdom denied.

Some say Romero was not killed because of the faith; he was “merely” a victim of a political assassination. He preached agitation, not the gospel, his critics say. They argue his martyrdom would be an embarrassment to brother bishops in El Salvador and other hotspots in Central America, where Romero had been vigorously denounced. And Pope John Paul II’s misgivings about liberation theology—owed in part to the decades he spent living behind the Iron Curtain—significantly impeded Romero’s sainthood cause.

But Romero was not a theologian of that kind of liberation; “Romero was a theologian of the Beatitudes,” his friend Roberto Cuellar said. “Give food to the hungry; give drink to the thirsty. . . . What impressed me about him was his ability to make the Beatitudes real—to defend the rights of the poor and later their human rights as well.”

Indeed, Óscar Romero was killed in odium fidei, in hatred of the faith. He died a martyr’s death not because he was shot through the heart while saying Mass, but because he dared to make real gospel demands for dignity and justice on behalf of the defenseless and marginalized in El Salvador.

Back in 1980 at that meeting in Washington, Robert White understood that it was faith—not revolution—that compelled this small, fearful man to heroic activism for the poor. And White martyred his own career trying in vain to make that simple distinction understood.

This column appeared in the March 2015 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 80, No. 3, page 39).

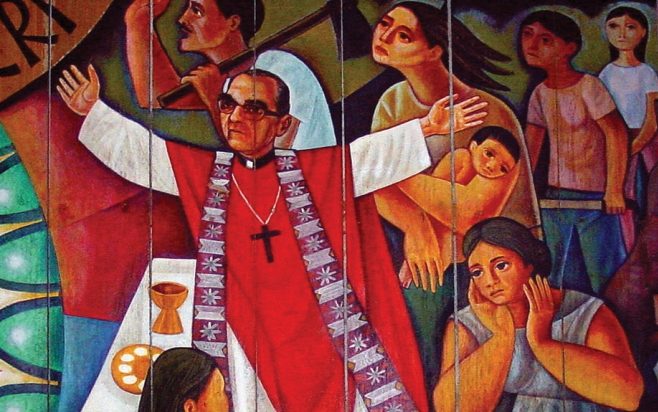

Image: The Claretians/Cerezo Barredo

This article is also available in Spanish.

Add comment