As I begin to write this, I’m sitting in the observation car of the California Zephyr. The time approaches 10 p.m., and the endless plains of Nebraska recede into the surrounding darkness. I sip scotch and write, hoping that a lithe Eva Marie Saint will step out of Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest, put a finger to my lips, and beckon me into her stateroom.

I know this probably won’t happen. My section of coach is full of German-speaking Mennonites from somewhere in Wisconsin—not the type for late-night rendezvous or sleeper cars, I’d imagine, although I do admire the bonnets. I’m not sure how blond double agents cross the country these days, but evidently train travel is a little out of fashion.

Walker Percy and his characters do everything in their power to escape the crushing weight of everyday existence. They wander aimlessly, go to movies, womanize (sometimes on trains!), and drink. A lot.

My introduction to Percy was a battered volume entitled Love in the Ruins: The Adventures of a Bad Catholic at a Time Near the End of the World (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux). The bad Catholic in question here is Dr. Thomas More, a tippling Louisiana doctor with a history of mental illness and an ex-wife who loved St. Francis of Assisi, “not because he loved Christ, but because he loved titmice.”

Fresh out of the psychiatric ward, and armed with his soul-diagnosing Ontological Lapsometer, More sets out to save a broken world—battling gin fizzes (he’s allergic to egg whites), a demonic businessman (out to use More’s invention for ill while simultaneously winning him the Nobel Prize), and the heavy burdens of everyday life. Eventually, More escapes to a dilapidated Howard Johnson’s stocked to the gills with the classics of world literature, cases of bourbon, and three women who are all in love with him.

Walker Percy’s early life was defined by tragedy. His grandfather died by suicide in 1917, going up into the attic and shooting himself in the head. In 1929 Percy’s father ended his life in the exact same manner. A number of years later, Walker’s mother drove her car into a lake and drowned. Her son never considered this to be an accident.

Raised from a young age by his war hero-cum-poet uncle, Will Percy, young Walker was soon introduced to the best of a Southern culture still reeling from the aftershocks of the Civil War. By adhering, for a least a time, to his uncle’s Southern brand of almost Greek stoicism, Percy found a reason to live where his ancestors had not.

Putting his faith in medicine, Walker Percy trained as a pathologist at Columbia University, earning a medical degree in 1941. He quickly became acquainted with the corpses of the New York City indigent population, and, shortly after the death of his uncle in 1942, Percy contracted tuberculosis while performing autopsies. He was sent to the Trudeau Sanatorium in Saranac Lake, New York for rest and recuperation.

Laid up in bed like Ignatius of Loyola, Percy had nothing to do but read. But rather than read the lives of the saints, Percy took up the Great Dane, 19th-century philosopher and theologian Søren Kierkegaard. Emerging in 1944, Percy no longer believed the pursuits of education and empirical science held all the answers.

He still found the draw of science alluring—many of his best characters being scientists and skeptics themselves. And while his best novels are rife with tension between science and faith, Percy had clearly put his own faith in a higher power. After examining the church’s position on evolution, Percy converted to Catholicism in 1947.

Echoing Kierkegaard, Percy believed that as long as you’re still on the search—for truth, beauty, or self—you’re still alive. To die is to get so caught up in the daily grind that we lose sight of these goals. No matter how we try to fill the void in our hearts with stuff, ideology, or food, we ourselves are still left over, remainders.

Eventually we have to turn to the mirror and deal with the mystery of ourselves—enfleshed spirits “on this insignificant cinder spinning away in a dark corner of the universe.” Walker Percy holds the mirror up for us. He won’t allow us to escape the absurdity of ourselves. We have a predicament shared in common: the suspicion that something is wrong. But, as he sits there, bourbon in hand, he’s smiling. At the end, he likes what he sees.

I undertook the quixotic train journey in the first paragraph as the sort of desperate search that a character of Percy’s might have embarked on. Tomorrow morning I’ll board the train again, this time with the same group of familiar but nameless commuters who move toward the northern peripheries of Chicago while the great masses press toward the downtown center. None of them look like Eva Marie Saint.

I’ll get off at the Linden station in Wilmette, Illinois, the northern-most station in the Chicago “L” network. Each day, it gives me some comfort to know that Binx Bolling, the hero of Percy’s very first novel, The Moviegoer (Vintage), ended his quest in exactly the same town where I stagger onto the pavement at 7:30 each morning, coffee in hand, and begin the daily walk to work.

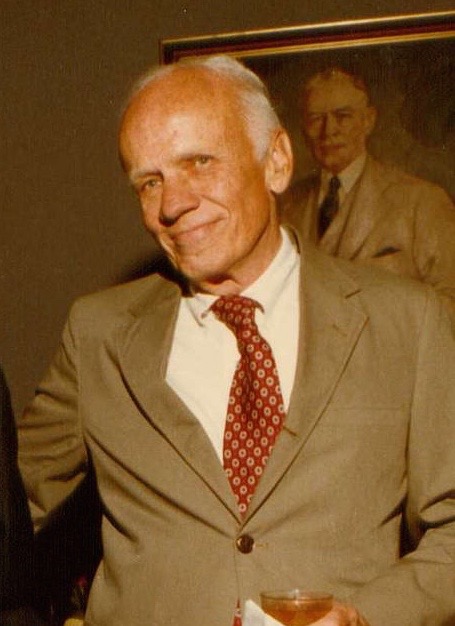

Image: Aspen Institute Pictures, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Add comment