Muhammad Ali downed some of the best boxers of all time, but his battle with the Supreme Court truly cemented his legacy.

First a warning, or a reassurance: HBO Films’ Muhammad Ali’s Greatest Fight, which premiered October 5, is not a highlight reel of Ali’s triumphs over Sonny Liston, Joe Frazier, or George Foreman. It is instead a behind-the-scenes courtroom drama about an even greater battle—the time that Ali fought the law, and the law lost.

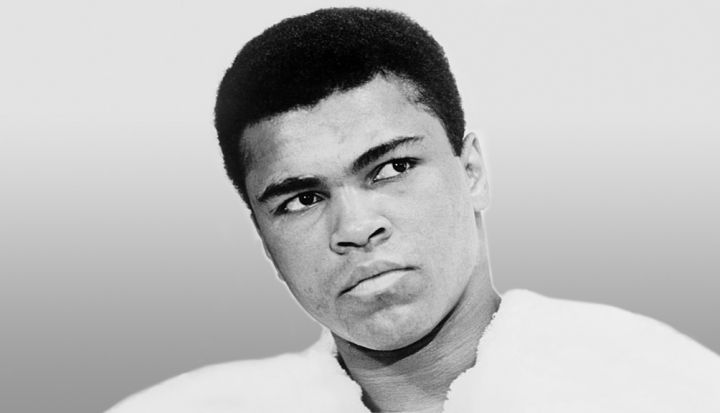

Younger Americans may only know Muhammad Ali as a silent trembling figure, stricken by Parkinson’s disease, a monument to his former self. Whenever the current Ali appears in public, we hear tributes to his courage and integrity, but rarely does anyone explain what he did outside the ring to earn this celebrity sainthood.

For that, you have to go back to Muhammad Ali in his prime. That was the man who, at his first championship fight, included Malcolm X in his ringside entourage. Shortly thereafter, the new champ announced his conversion to Islam and repudiated his “slave name”—Cassius Marcellus Clay. That Muhammad Ali was the man who, in 1967, refused induction into the U.S. Army because, as he put it, “I ain’t got no quarrel with the Viet Cong.”

That’s where the story of Ali’s vaunted courage and integrity begins. He had the guts to stand against his country’s government during a time of war. In 1967 most Americans still supported their president on Vietnam, and Ali’s implication that we were a racist nation engaged in a racist war was downright shocking. Retribution was swift. Ali lost his title as heavyweight boxing champion and was effectively banned from the sport. Meanwhile, the federal government pressed criminal charges and Ali was sentenced to five years imprisonment.

That’s where the HBO film picks up. Ali’s lawyers appealed his case all the way to the Supreme Court, claiming that his religious opposition to the Vietnam War, based on the teaching of the Nation of Islam, should qualify him for conscientious objector status. Under Chief Justice Earl Warren, the court was dominated by liberals who might welcome the opportunity to make a statement against the war.

But by 1971 President Nixon had appointed a new chief justice, Warren Burger (played in the film by Frank Langella), and his “Minnesota twin,” Harry Blackmun (Ed Begley Jr.). Those two combined with the moderate Kennedy appointee Byron White and the Eisenhower conservative John Harlan to support the government’s case against Ali. Thurgood Marshall (Danny Glover) had been U.S. solicitor general when the Ali prosecution began, so he recused himself from the case, leaving the vote a 4-4 tie. That meant the lower court ruling would stand. Ali would go to jail, and Justice Harlan (Christopher Plummer) was assigned to write the opinion.

In the film, while the justices deliberate, their young clerks debate the case and bet on its outcome, and the streets of Washington fill with antiwar protestors. At the same time we, the viewers, are treated to numerous archival film clips of Muhammad Ali explaining himself, his faith, and his view of the war. The footage of young Ali is electrifying. First we see him rhyming about his boxing prowess, but later, with his career on hold and prison waiting, things get more serious. Ali’s claim to conscientious objector status was based on religion, but his objection to the Vietnam War was also political. Why, he asks, should he, a black man, go kill brown men, for freedom he doesn’t even have himself?

Back at the court, the aged Harlan is engaged in a tug of war with his new clerk, Kevin Connolly (Benjamin Walker), who drafts for him a brief supporting Ali’s appeal. Enraged, Harlan orders it rewritten to reflect the prevailing opinion of the court. But Harlan reconsiders as he reads the Quran and Nation of Islam founder Elijah Muhammad’s Message to the Blackman.

The outcome of the case is no surprise, but the film’s story of how the Supreme Court got there is new. And the Upstairs, Downstairs interplay between the justices and their clerks is fascinating. But the court scenes in Ali’s Greatest Fight are especially interesting for their depiction of intra-court politics. In those days, long before Scalia and Thomas, the justices did ideological battle but they could also be swayed by reason, and they could still circle the wagons for the good of the country.

In the end, the Ali decision is unanimous. Even Burger, despite pressure from the Nixon White House, finally joins the majority, convinced that a vote to jail Ali would be perceived as racist and could intensify social unrest in the streets. At that moment, the viewer can’t help but think of the many partisan and divisive Supreme Court rulings of the recent past, from Bush v. Gore to this year’s ruling against the Voting Rights Act, all rammed through on 5-4 votes. It’s enough to generate a wave of nostalgia for the Nixon era and the Burger court.

Meanwhile, Ali’s portions of the film leave us to mourn the triviality and materialism of more recent sports “heroes.” It’s hard to imagine LeBron James or any of his peers taking a stand that would cost them a dollar, and certainly in boxing the fall from Ali to Mike Tyson was long and steep. Perhaps a new generation of athlete-activists will be born from gay rights protests at next year’s Russian Olympics. But for now there is no competition. When he risked his career and his freedom to honor his conscience, Muhammad Ali truly was “The Greatest.”

This article appeared in the November 2013 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 78, No. 11, pages 40-41).

Image: Wikimedia Commons cc by Library of Congress

Add comment