Mobile, Alabama in autumn feels mutable, sunshine floating down on its filigreed iron railings and azalea gardens, then, suddenly, dispiritingly humid. It’s not just the humidity that weighs on you, it’s the history: the lingering horror of slave markets, cross burnings, and even the 1981 lynching of Michael Donald, a 19-year-old African American, chosen at random, who had been walking home from a convenience store.

I was in Mobile researching a book about the South and its influence on American culture. I was also trying to understand my feelings about my own Southern—and American—heritage. I listened as Scotty Kirkland, curator of history for the Museum of Mobile, led a tour of the city’s civil rights history. He emphasized progress, but it was impossible not to lament the brutal sickness of racism that is woven into Alabama’s and America’s story, in such counterpoint to the faith and courage epitomized by 1950s and ’60s civil rights heroes.

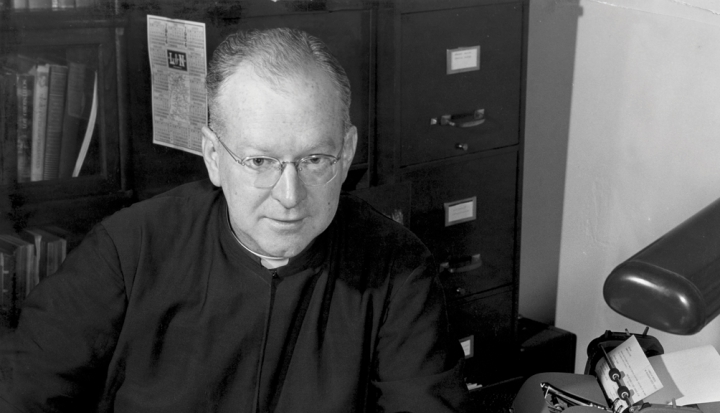

I felt sad that there weren’t more Catholic leaders on that uplifting side of history. With the church’s powerful social justice tradition, why weren’t there more Catholics? So I was grateful when Kirkland pointed me toward Jesuit Father Albert Sidney Foley, who began working for civil rights in the 1940s in Alabama, the state that, more than any other, was at the bloody heart of the civil rights struggle.

Foley, born in New Orleans in 1912, grew up in a world that became more segregated with each passing year. Like most white Southerners, he didn’t give it much thought. Indeed, as a boy he found the racist film The Birth of a Nation to be inspiring.

The church didn’t take a strong stand either. Racism’s reign of normalized terror—from murder to casual disrespect—meant that was just the way things were. The Ku Klux Klan included anti-Catholic messaging in its rhetoric, and the hierarchy in the South was cautious—overly cautious—about speaking out.

Everything changed for Foley in 1943, when, as a young Jesuit, he was assigned to teach the class “Migration, Immigration, and Race” at Spring Hill College in Mobile. His research—which included interviewing local black Catholics and wide-ranging reading—opened his eyes: Segregation was sinful. He looked to the church fathers and social justice teachings to better understand his new realization and to discern what should be done.

Foley’s experience resonated with me. As I research and interview people for articles on justice issues, I, too, come to new understandings. I then turn to church teachings to better understand what I’m learning. Foley modeled for me how a person could best be an informed part of the cultural conversation, listening to others and responsibly speaking out. He then also took the next step, taking action in ways that exposed hypocrisy and lethargy.

He almost immediately got into trouble. Mobile Bishop Thomas Toolen warned him to stay away from the issue of “social equality, which leads to nothing but trouble.” That didn’t stop Foley from organizing student activities, bringing together white and African American students. When Toolen learned about the plans for an integrated pilgrimage in 1944, he insisted that Foley be reassigned.

Foley returned to Spring Hill in 1953 to teach sociology. As chairman of both the Mobile chapter of the Alabama Council on Human Relations and the Alabama Advisory Committee to the United States Civil Rights Commission, he worked with Martin Luther King Jr. and other luminaries of the civil rights movement.

He publicly criticized the church’s hesitance in taking a stand on segregation and racism. He maintained that church leaders should “reassert the traditional position of the church as the highest moral authority in these matters of justice and right.”

In 1956 Foley authored two model ordinances for Mobile. One would ban police from KKK membership, the other would ban “intimidation by exhibit,” i.e., cross burning. In response, the Klan ran an advertisement denouncing Foley as a “man of large profession and small deeds, a communist and quisling of foreign seed who wants to write new city ordinances.”

Foley appealed to the FBI, figuring they were past due in restraining the Klan’s arsons, lynchings, and bombings. After all, the peaceful NAACP was illegal in Alabama at the time. When the FBI didn’t respond, Foley set about doing their job for them.

The scrappy, pragmatic Jesuit bought a list of license plate numbers from the state and paid people to park outside Klan meetings and record the license numbers of the mask-wearing attendees. This might have ended badly; one night he and other observers were followed after they’d done their spying. No one got hurt, though, and Foley soon knew who was active in what he called the “dunce cap and bedsheet brigade.” He paid informants to infiltrate KKK meetings and even rented the apartment above that of Mobile’s “imperial wizard” Elmo Barnard.

One January night in 1957 the Klan retaliated. They arrived on Spring Hill’s campus in a caravan of cars. Before the robed men could erect their cross, however, Spring Hill students raised an alarm and poured out of nearby dorms to chase them away.

Foley would continue to teach at Spring Hill and lead workshops on social justice issues until his death in 1990.

As far as we’ve come, America’s racist past isn’t dead. I can imagine what Foley, that Jesuit sociologist, might say about 17-year-old Trayvon Martin’s “stand your ground” murder in 2012 or about the weakening of voting rights legislation earlier this year. His words would be informed and passionate, and they would echo Catholic social justice teachings.

That’s how I want my words to be as well.

This article appeared in the November 2013 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 78, No. 11, pages 47-48).

Image: Courtesy of Spring Hill College Archives

Add comment