Even if you’re eligible for AARP, don’t be a snob about young adult fiction. It’s some of the most creative literature around.

This spring I took a class called “Writing the Young Adult Novel.” I’ve long been interested in penning a contribution to one of my favorite literary genres, ever since I was once a young adult. While I had considered myself relatively up on which young adult (YA) authors to pay attention to, I realized I’d merely been sticking my toes in the genre.

It’s hard to avoid the strong hold that YA fiction has taken on popular culture in the past decade. We can blame that on (or thank) the story of a boy wizard with a lightning-shaped scar. J. K. Rowling’s seven-part tale of Harry Potter and his friends was extraordinarily fun to read not just for middle schoolers but for their parents, too. Just days after the final book was released, while riding the train to work, I counted four people with their noses in copies.

What’s remarkable about such a phenomenon is the lack of sheepishness about toting around a copy of a book written for kids and young adults. The books’ themes of loss, persistence, loyalty, and courage (among others) appeal to readers of any age, and Rowling’s superior writing presented them honestly and gave them the gravity they deserved.

She cleared the path for the trends that quickly followed: romances with vampires and werewolves, and later, chronicles of teenage heroes in a dystopian future earth. Twilight, The Hunger Games, and Divergent have all become franchises similar to Harry Potter (minus the theme park), but they all began as books written for young readers that have also been consumed by adults.

David Levithan, publisher and editorial director for Scholastic, told Newsweek several years ago that this second golden age of YA literature (the first being in the late 1960s and 1970s, when books such as Judy Blume’s controversial Forever were first published) is the result not just of good writing, but, among other factors, an increasing awareness of the genre as its own thing, separate from children’s literature.

A similar acknowledgement is taking place in the church as ministers and pastors call for better, more age-appropriate tools for catechesis and young adult spiritual development. Until recently, as with literature, there had been only two designations: children and adult.

In my class, when one student suggested that perhaps today’s adults are just more immature readers than previous generations, the rest of us got predictably defensive and named all the reasons an adult might read and enjoy YA literature. I’m a sucker for a satisfying plot, which I think the YA genre delivers more consistently than a lot of adult fiction. And without the baggage of a lifetime of mistakes and experiences, teenage characters are focused and pure even in their intentions and narrative. Even in the darkest, most dystopian tales I’ve read, there is hope and a sense that all of the drama, emotion, and intensity of teenage experiences matter.

If you’re willing to go past the end caps devoted to the latest literary franchise, you’ll find some special stuff that can appeal to more than just the teen set. Books like David Levithan’s Every Day, which follows the life of A., who wakes up in a different body each day. Levithan’s most recent book beautifully explores questions about identity and personhood. Frankly, it’s a service to the young adult reader to assume they want to grapple with questions of such gravity: What makes a person a person? Is it a body? Is it a mind? Is it a soul? Can these things be separated?

I recently finished reading Feed by M. T. Anderson. Hauntingly prescient (the book came out in 2002), Feed explores the pressing in of consumer culture to such an extent that it becomes a part of the very makeup of our brains. Anderson is a master of prose, and the humor and sting of satire is present right down to the words the characters use as slang. It feels at once familiar and otherworldly. The author is a successful children’s author, but he lets his imagination run just as wild in his books geared toward older readers.

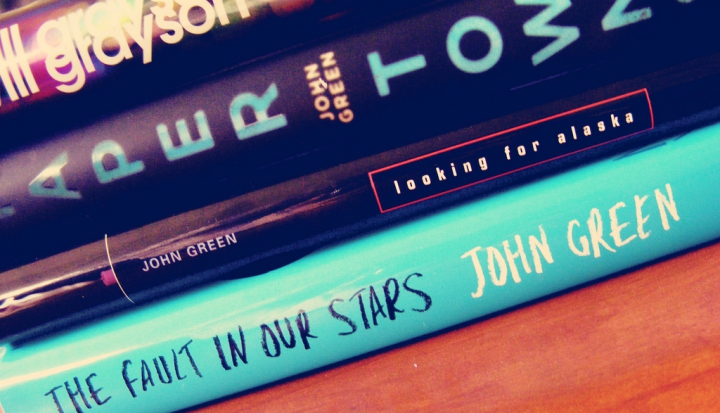

I know many people who have John Green to thank for opening up their reading repertoire to include the YA genre. Green writes with the assumption that teens are just as smart as he is. In Looking for Alaska, the day-to-day issues that young adults face—crushes, friendships, homework, and teachers—are given credence and appropriate urgency. Like plenty of other YA novels, this one takes place at a boarding school, a device that conveniently rids the characters of parents who could otherwise get in the way of plot. Green’s characters are regular teens figuring themselves out, trying to fit in, and discovering life’s twisted mysteries.

In my class I had the privilege of reading some nascent novels that make me optimistic about the future of the written word. One classmate was writing about a Type A gymnast whose competitiveness was driving a wedge between her and her friends. Another was exploring the life of a high-functioning autistic girl dealing with the aftermath of her identical twin sister’s mysterious death. Race and politics in Detroit were major themes of one classmate’s completed first draft.

There has been lots of hand-wringing about the younger generation. We grown-ups may cluck our tongues and shake our heads in frustration and superiority when we see them typing away madly with their thumbs on their phones. We talk forlornly about the dumbing down of culture.

Before you find yourself expounding to a teen about how things were when you were their age, pick up a YA book written in the past decade. You’ll see how much you have in common.

This article appeared in the August 2013 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 78, No. 8, pages 40-41).

Image: Flickr photo cc by sonyazombiee

Add comment