Suffering meets consolation in the Chaplet of the Divine Mercy.

For the sake of his sorrowful passion . . .

It was 3 p.m. and it was time to say the Chaplet of the Divine Mercy. I had a rosary in my hands and was counting out the litany in the midst of a small prayer group that I had been invited to join for the day.

It was hard for me to focus since I was afraid I would be called upon by the group leader to lead the next set. I chuckled to myself at the reversal of roles: I realized how my college students must feel when my eyes scan the class looking for someone to make eye contact with so that I can ask about the day’s reading. I hadn’t done my homework and came unprepared with none of the chaplet prayers memorized.

The leader passed me over and asked the woman in front of me to begin the next set.

For the sake of his sorrowful passion . . .

As a Catholic and college professor, I sometimes find myself torn between insider and outsider perspectives concerning Catholic devotions.

As far as the “insider” part of me goes, saying the chaplet has a link to my most tender childhood memory. My grandmother would say her rosary next to my bed since I was afraid of the dark. And so whenever I’d take out my rosary beads to say the Chaplet of the Divine Mercy, I’d have a warm, comfortable feeling.

Although I had never said the devotion alone, as a “Catholic insider” I was always eager to practice it in a group.

But looking at the devotion as an outsider, it did have some undeniably controversial elements. The devotion was revealed through visions and locutions to a Polish nun and stigmatist, Maria Faustina Kowalska, who died in 1938 at the age of 33.

If visions, locutions, and stigmata weren’t enough, there was Faustina’s insistence that the chaplet be said at 3 p.m. (the time of Jesus’ death) and that those who recite the chaplet would receive “great mercy” at the moment of death.

Putting all this together with other ostentatious claims about the chaplet somehow being related to the end times, it was surprising that a normally cautious institution like the Catholic Church would promote it.

But devotion to the divine mercy resonated with the spirituality of Pope John Paul II, and he made his fellow Pole Faustina Kowalska the first saint of the new millennium. The Sunday after Easter is now called Divine Mercy Sunday.

For the sake of his sorrowful passion . . .

It was the Sunday following Divine Mercy Sunday when I was saying the chaplet, having just been passed over by the leader of the small prayer gathering. He had given his own personal testimony about how he had experienced the divine mercy in his own life: He had forgiven his wife for an affair, and they had rededicated themselves to their marriage.

After the chaplet ended, members of the group began to mingle and talk. One woman spoke of how her breast cancer had metastasized, another spoke about how her kidney disease had reached its final stage. A couple shared their experience of losing their child, and a nun mentioned that she was about to lose her only sister to a rapidly advancing illness.

That Sunday there probably were some who were praying for the specific graces promised to Faustina in her visions. Perhaps some thought that invoking the divine mercy was a prelude to the immanent vindication of God at the end of days. But if this was the case, it was hidden from my eyes and ears.

Instead, everyone simply shared the consolations they received during their encounters with illness and loss.

It was then that I realized that the core of the divine mercy devotion really did not have to do with locutions, visions, or stigmata. The devotion was about how the love elicited by suffering reveals the divine mercy. Through sharing grief in a community, divine mercy helps us move beyond sadness and despair.

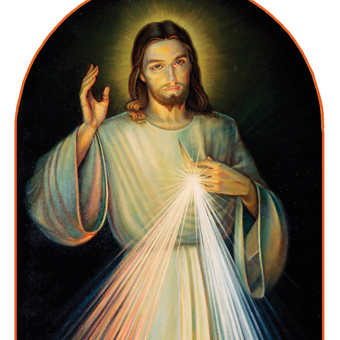

St. Faustina’s image of The Divine mercy shows Jesus with his right hand extended and two rays of light

shining from his heart to illuminate the world.

Faustina wrote that Jesus told her the rays “represent blood and water,” an allusion to the saving blood and water pouring from his side as he was pierced on the cross. One could also interpret the rays as reflections of the divine and human aspects of mercy incarnate in Jesus, true God and true human. We experience divine mercy when we experience human mercy.

I have to admit that I don’t drop everything at 3 p.m. to say the chaplet. But I can admit that I sometimes say it alone, for even in solitude I can feel the sense of community and connectedness that makes God’s mercy real.

For the sake of his sorrowful passion, have mercy on us and on the whole world.

This article appeared on the October 2008 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 73, No. 10, pages 37-38).

Add comment