Flesh and blood deserve equal billing with spirit and soul when talking about human nature.

The children next door are sidewalk theologians—in their spare time, of course. Modern children lead unnaturally busy lives. They go to school five days a week and attend Sunday school on weekends. They have an exhaustive activities schedule coordinated by their parents. And they also play, among the most sobering and time-consuming responsibilities of childhood.

The little boy, perhaps 6, tends to appear on his lawn in a cowboy hat with holsters strapped around his hips. He’s rather shy and prefers to peep out at the world from behind a tree. His sister, a few years older, makes her appearance sometimes as a fairy and sometimes as a ladybug, species optional, wings mandatory. She flits liberally and magnificently around the front yard as if considering a run for public office.

Neither of these children look much like theologians, which proves that looks are deceiving.

The children are good with chalk, especially the older sister. They decorate the entire sidewalk in front of their house with the predictable hearts, flowers, and stars in pink, blue, and yellow. The grid for hopscotch is also omnipresent.

This stretch of pavement gets a lot of foot traffic between the library on one end of the block and the post office on the other, so the kids have to renew their artistic efforts weekly to ensure their survival.

Their career in theology mysteriously began the week that Apple founder Steve Jobs died. It’s unclear how this event triggered a new vocation that didn’t involve guns or wings. The family computer could be a Mac.

All of a sudden, Jobs-isms sprouted on the sidewalk in the midst of the flowers: “Being the richest man in the cemetery doesn’t matter to me,” the sidewalk proclaimed that week. A few days later: “We just know there’s something much bigger than any of us here. —SJ”

Finally, Jobs’ last reported words appeared in large blue caps: “OH WOW, OH WOW, OH WOW.”

It was hard not to study the pavement more seriously after that. My small neighbors followed up their foray into meditation a week later with another dead philosopher: “You may say that I’m a dreamer, but I’m not the only one,” John Lennon declared underfoot. Not only was the family computer a Mac, but the parents were vintage rockers. Other passersby began to slow down and walk around the chalk respectfully, even going into the gutter or up onto the lawn to avoid smudging the words.

Some weeks later, however, the kids tipped their hand. Printed across the walk in all three colors: “You do not have a soul. You are a soul. You have a body.” What was this? A recitation of last week’s Sunday school lesson? Or something Mom said last night before she turned out the light? I had to go Googling to find out. The source of the quote: English spiritual writer C. S. Lewis.

I began to suspect the kids were being coached. Or there’s something really odd about that chalk.

This time I was the one veering off into the gutter to respect the words. I carried them around for the rest of the day. You do not have a soul, you are a soul, you have a body. Do I believe that? Or rather, is that what we believe?

It contradicts Thomas Aquinas, for one. He believed the human body is an essential aspect of the human person. You cannot say a human being “has” a body when it’s the nature of a human being to consist of both soul and body. And since it’s the nature of a soul to be incorruptible, Aquinas further argued, there is something about the body that is likewise incorruptible. Cue the glorified body we’re taught to anticipate in eternity.

Meanwhile our present generation, hung up on possessions, views personhood in terms of ownership. I possess my body. It’s mine to do with as I please. A lawyer explained to me that I own not simply my body but also the six inches of space around it, so that if anyone moves into that proximity, I have territorial rights protected by law that can be invoked. At least in this country.

If, however, I decline to consider the body as one more thing to be possessed, then what? Humanity spins into a spectacular new dimension, that’s what.

To be essentially soul and body means that the self cannot be defined principally in terms of one or the other. I’m not just a soul temporarily nesting in a shell of irrelevant flesh. Nor am I a lustily vital body temporarily animated by some elaborate chemical soup that religious people like to call a soul.

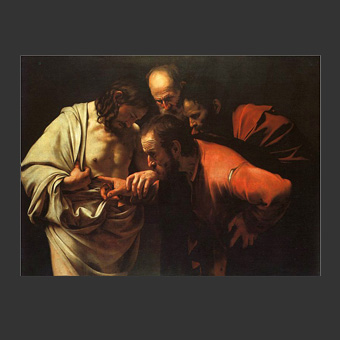

If I am essentially both, as Jesus is God and flesh according to our creeds, then neither is about to disappear. “Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up,” Jesus tells his detractors. What’s more, when he reappears, Jesus does have a tangible body that eats and drinks, with familiar wounds that can be explored by the hand of a friend.

Yet it’s painfully clear that the body we presently “are” does not last, not on terms we perceive and understand, anyway. The body betrays, weakens, sickens, and dies. It fails us on every front, losing its original lines, its youthful strength, its easy function. It’s hard to credit that we are a body or can hope to remain one when the only viable part of us appears to be the essence we cannot touch.

Despite all that, our loyalty to the body is fiercer than to the soul, since the body’s been our solitary address all these years. If someone tells you their only allegiance is to the soul, just hold a match to them for a second. I’ve known good and holy friends who approached death believing resolutely in the life of their immortal souls. Yet they still cried when chemo shed their hair, when stroke took their words away, when morphine couldn’t dull the pain, and when their failing bodies humbly soiled the sheets.

Destroy this temple, and it will be restored. That’s a promise. That this temple can and will be destroyed is also without a doubt. The giver of body and soul pledges that a grain of wheat falling to the ground will bear much fruit. But first it has to fall. And maybe the most convincing evidence that we are a body, every bit as much as we are a soul, is that we can’t bear the loss of this animal, not even when its further existence is insupportable.

We can’t separate our self-understanding from the creature we are. If what our faith teaches is to be believed, we won’t have to for long. Or as the iPod theologian put it: We just know there’s something much bigger than any of us here. Oh wow.

This article appeared in the March 2012 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 77, No. 3, pages 44-46).

Add comment