“But about that day and hour no one knows,” Jesus said in talking about his return at the end of time, “neither the angels of heaven, nor the Son, but only the Father” (Matt. 24:36). Note: That’s the Son talking.

Or how about in the Gospel of Luke where the story of Jesus’ childhood ends with the words, “And Jesus increased in wisdom and in years” (Luke 2:52).

In the Gospel of John it appeared Jesus didn’t know his friend Lazarus had died, and on the cross in Mark’s gospel he thought God had abandoned him. In other words, it looks as if he didn’t know certain things and he learned.

For many Christians, to question Jesus’ all-knowingness smacks of irreverence and even blasphemy. If God knows everything and Jesus is God, then Jesus must have known everything, right? Doesn’t thinking that Jesus walked the earth with anything less than the total knowledge of everything that was and was to be take away from his divinity?

Jesus-as-all knowing, however, runs into another basic Christian belief about him: that he was fully human in every way except for sin. To be human means to have human limitations. Does even a morally perfect person like Jesus get an exemption from not being able to know everything all the time? Doesn’t thinking anything else take away from Jesus’ humanity?

The question is dicey because it quickly blows up into the matter of Christ’s divinity and humanity, and the church has been fighting pitched theological battles over that issue since its early centuries. So it’s not surprising that to deal with what Jesus knew and when he knew it, theology has had to walk some pretty fine lines.

The key doctrinal jumping-off point is that when Jesus came into the world, the divine nature took on but did not replace his human nature. His divinity made room for his humanity; his human life expressed divine life without diminishing either. In his human knowledge Jesus understood who he was, but like any human being he grew into that awareness, even though it was the totally unique vocation of being the Son of God.

That his learning was perfect doesn’t mean he didn’t need to learn. In fact, his flawless desire to do the Father’s will gave human beings the model to do the same, even if his perfection is not quite within reach. And that’s a good thing.

“We do not have a high priest who is unable to sympathize with our weaknesses,” the Letter to the Hebrews says of Christ, “but one who has similarly been tested in every way, yet without sin” (Heb. 4:15). Jesus’ earthly life opened the door for humanity to enter into divine life in a new way, and his growth in wisdom and knowledge of the ways of God lets his creatures do the same.

This article appeared in the September 2011 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 76, No. 9, page 54).

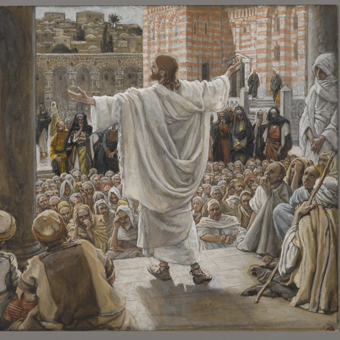

Image: James Joseph Jacques Tissot/Brooklyn Museum

Add comment