She spoke little English — just isolated words you had to build the intended sentence around in your mind. But it never seemed to get in the way of our conversation. Mrs. Sottopietra was the oldest human being I’d ever seen, though every old person seems a hundred from the perspective of a child.

She lived in the tiny house bordering ours, with the world’s smallest garden. Her “yard” was just a space to the side of the brick steps leading up to her porch, enclosed by a wrought iron fence that kept out more than it held within. That was the mystery: how she made a postagestamp-sized garden into such a land of wonder.

Sometimes when we played ball in the street, the object of our pursuit would wind up on the far side of her gate. If such a thing happened, say, at the Martelli’s down the street, we would instinctively kiss that ball goodbye and go play something else. Some neighbors were like grizzly bears, not worth confronting in their lairs.

If something landed in Mrs. Sottopietra’s yard . . . it might become an opportunity to engage one of the most extraordinary souls in the neighborhood.

But if something landed in Mrs. Sottopietra’s yard, it was no big deal. In fact, it might become an opportunity to engage one of the most extraordinary souls in the neighborhood. If the house seemed quiet and she might be napping, we’d carefully open the gate and tiptoe inside, rescuing the ball without disturbing her.

But often as not, as soon as the gate released its slight squeak of protest at being moved, the screen door would open and Mrs. Sottopietra would stick out her head. Her hair was creamy white and pulled into a bun in the back.

Her face was a contour of deep creases in leathery olive skin, with eyes like shining onyx stones embedded in it. Every crevice of her face seemed to be made for smiling, as if she’d practiced all her life and these amazing wrinkles were the sculptured result.

“Sorry, Mrs. Sottopietra. Our ball is in your yard.”

“Ball?” She’d repeat the word experimentally, as if the sound were novel to her ears. “Bawl?” The child would point to the object in question, and the old woman would step cautiously down the brick steps as if they might break under her slight weight. Then, stooping, she would reach into the thorny bushes and retrieve the sphere–”Bawl!”–and return it to its owner with the mildest, kindest expression in her eyes, to affirm her boundless good will concerning the disturbance. We would retreat from her territory at once, to honor her privacy. But invariably she would call us back, beckoning with both hands. “You? See?”

I always returned to see. She wanted to show us her roses. With an infinitely delicate touch remarkable in her large coarsely lined hands, she’d lift the head of this bloom and that one.

When standing this close to the roses she would whisper, as if afraid to disturb their peace. The miracle was that she had a dozen kinds of roses in every color in that impossibly little space. Their fragrance was heady and sweet, unrivaled by any rose I’ve smelled in the 40 years since.

Mrs. Sottopietra would put her face close to one of those blooms and inhale. “Beautee-ful,” she would say, tears welling up in her eyes. How she loved those flowers.

“Beautiful,” I would murmur in agreement, smelling a rose courteously. And for some reason I did not understand, my eyes would grow moist, too. “Nice girl,” she’d whisper softly, as if not to awaken the flowers.

This was my first experience with transfiguration, though I didn’t know that then.

This was my first experience with transfiguration, though I didn’t know that then. I knew nothing of this old woman: what life had been like in her country far away, what troubles she bore, what loneliness might accompany living in a world where you could not speak to your neighbors. I didn’t know anything about all the years signified by those deep creases on her face.

All I knew was that this tiny old woman, when standing in her garden whispering over her roses, was the most beautiful person I’d ever seen. Her radiant smile and the tears standing in her eyes made me think of God and how being in her yard was a little like being in church: hushed, peaceful, holy, safe.

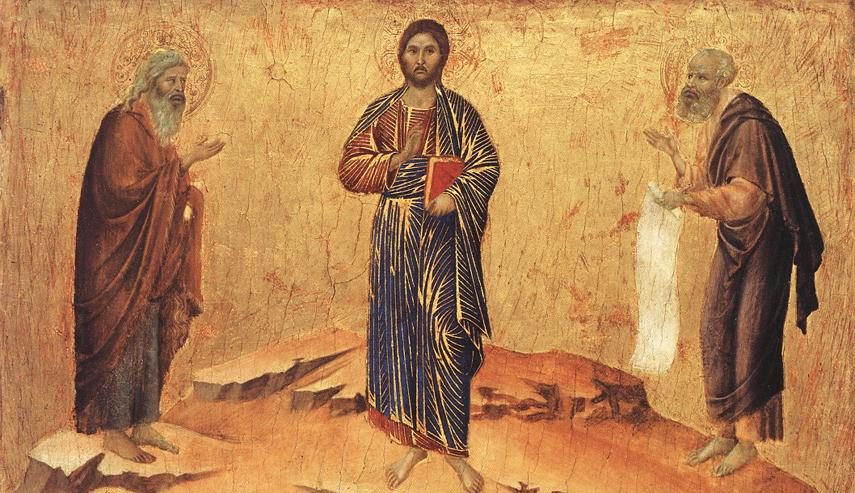

The disciples saw something quite different, perhaps, when they awoke from their usual nap while Jesus was praying, and discovered their teacher transfigured. All of the gospel accounts speak of a brilliance no human factor could achieve. No bleach could make his garments that white; no light could shine as his face did.

In this startling revelation, they saw their teacher–a man they no doubt thought the world of–in conversation with the two greatest figures of Hebrew history, Moses and Elijah. No leader rivaled the authority of Moses, the only human with the courage to speak to God face to face and therefore to receive the law. And no prophet had the power of Elijah, who could raise the dead and command the elements in accordance with God’s will.

These men were giants in the religious imagination, and to find Jesus among them as a peer must have been mind blowing. But more than a peer: as the revelation waned and Jesus was left standing alone, it might have occurred to the disciples that Jesus had superseded the legacy of the law and the prophets, not simply stood equal to it.

But it did not occur to them, as scripture writer Father Paul Boudreau has noted. Peter’s question “Shall I erect three tents? One for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah?” betrays his confusion, not to mention his preference.

Peter would like to hang onto all three brands of authority: the gospel, the law, and the prophets. Peter doesn’t want to have any of his allegiances challenged. He doesn’t want to make a hierarchy of his values. As he proves so many times in the gospels and in the Acts of the Apostles, Peter would like to remain a card-carrying Jew in good standing, as well as a true student in the school of Jesus. If he can escape the crisis of having to choose which authority has ultimate reign over his life, he will gladly do it.

Peter is not alone in his preference. The first generation of the church was largely composed of Jewish Chrisbans trying fervently to be both. Later Christians would make a similar attempt to marry church and state, thinking that a merge between the two would be profitable to both and cause no serious threat to either.

Today not a few of us find ourselves with allegiances in several conflicting camps, “lighting candles at too many altars,” as a poet once said, working to keep all of our gods on speaking terms. And while we are trying to get away with such trespass, to recover our ball and slip away with no harm done, something is being revealed to us that we must not miss.

Nothing had changed, except perhaps their perception of him.

Jesus seemed no different when the disciples hiked down the mountain behind him. His face no longer glowed, his clothes resumed their dusty appearance. Nothing had changed, except perhaps their perception of him. Who was he, really? What did they really know about him? And which was more true: the man they saw before them now, a little tired, hungry, talking his usual mysterious language about the Son of Man rising from the dead? Or the wondrous being they had glimpsed on the mountain, conferring with legendary saints?

He charged them not to talk to anyone about what they had just seen. In some ways, that made it easier to file it away and pretend nothing had happened. They could forget that a voice from heaven had called him “my beloved Son.” Or that they had, for a moment, seen a beauty that made the tears come inexplicably to their eyes.

If they had held onto that vision and not forgotten what they saw, they might have recognized it again during that final meal on the night he was betrayed, when he took bread and gave thanks. They may have been able to accompany him to the cross, look upon that holy face, and not be overwhelmed with despair. They might have known, through those dreadful three days, that there was nothing to fear. They would have understood that when you bury a seed in the ground, it dies, only to produce its fruit.

But the church reminds us of this story twice every year, once during Lent, and once on the feast of Transfiguration, so that we do not forget and miss the transfigurings that come to us.

Like that of the homeless man who sits every day on the corner and asks for money, most days he is indistinguishable from the armies of homeless people I’ve met in every city. But once, on that wild election day some years back when the Florida count was uncertain and nobody knew who the next president would be, the man on the corner did not ask me for money. He asked me what I was hearing about the election. So I stooped down and started discussing the latest polling results. All of a sudden we were two Americans involved in civic affairs.

It did not matter that I was going home to dinner and he would be off to find a rolled up blanket behind a bush after dark. I try to remember the glimpse I had behind that dulled expression to the whole human being whose reality is a lot like mine.

Or how about the apartment-house neighbor who wore me down with her endless stream of poorly chosen romances and cyclical heartbreaks? She seemed the very definition of an unstable personality, ever red-eyed over some lover, a person hard to take seriously.

Yet she was a fine dancer. One night I attended a performance of hers and caught something in her face I had not expected to see. She was completely enveloped in the dance, at the poignant convergence of music and grace. She was focused, centered, balanced with a precision that was breathtaking. I did not recognize the precarious person who lived perched on the edge of reason. Here was quite another woman, whose body was the vessel of perfect knowing.

The glimpses of revelation are legion, once you start looking for them. The pregnant teen at the shelter starts to have the look of the Madonna about her, full of holy light and impossible faith in that tiny life within her. The organist at the cathedral is tethered to drugs, tragically made a thief and liar by his addiction. Yet when he plays that organ on Sundays, he is mystically transfigured into the instrument of God’s mercy and healing and joy to thousands.

The beloved sons and daughters of God are everywhere, and if we cannot see them, it might be we have forgotten something we once saw. We slipped into the yard, grabbed the ball, and missed the rose.

This article appeared in the March 2003 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 68, No. 3, pages 43-47).

Image: Duccio di Buoninsegna / Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Add comment