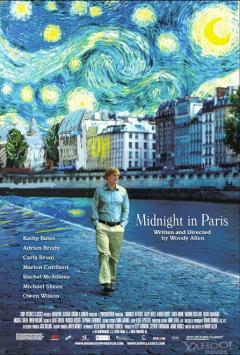

Midnight in Paris

Directed by Woody Allen (Sony Pictures, 2011)

When I was a doctoral student in Paris in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, I used to fantasize about the Paris of the 13th century, when my hero, Thomas Aquinas, was composing his theological masterpieces and when the cathedral of Notre Dame and the Sainte Chapelle were being brought to completion. From the perspective of late 20th-century Paris, when a bored skepticism held sway in much of the high culture, that time when ardent faith and high intellectual achievement went hand in hand seemed to me a golden age indeed. It is just this tendency to hanker nostalgically after a beautiful lost epoch that Woody Allen affectionately mocks in his witty new film, Midnight in Paris.

When I was a doctoral student in Paris in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, I used to fantasize about the Paris of the 13th century, when my hero, Thomas Aquinas, was composing his theological masterpieces and when the cathedral of Notre Dame and the Sainte Chapelle were being brought to completion. From the perspective of late 20th-century Paris, when a bored skepticism held sway in much of the high culture, that time when ardent faith and high intellectual achievement went hand in hand seemed to me a golden age indeed. It is just this tendency to hanker nostalgically after a beautiful lost epoch that Woody Allen affectionately mocks in his witty new film, Midnight in Paris.

The story centers around Gil Pender, a writer of third-rate Hollywood movies who longs to compose a great novel, like those of Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Gil finds himself with his fiancée in modern-day Paris, but the present interests him much less than the roaring-20s when his heroes strode the cultural stage in the city of lights.

Tired after a late night stroll through the city, Gil reclines on a set of stairs and considers his sad condition. Suddenly, a car from the 1920’s pulls up, and a group of revelers beckon him to join them. They deliver him to a rollicking gathering where he meets a young woman, in full flapper mode, who introduces herself as “Zelda,” and her husband, who blandly presents himself as “Scott Fitzgerald.” While Gil tries to make sense of what can only be an elaborate prank, he spies Cole Porter at the piano, singing one of his most fetching lyrics, and then, to his utter astonishment, a dashing, black-mustachioed young man enters the room and is greeted as “Hemingway.” Gil realizes that he has indeed passed through a sort of time warp into the Paris of the 1920’s.

In the course of three or four visits to this new/old world, Gil manages to meet most of the major cultural players of the period. Besides Hemingway, Porter, and Fitzgerald, he runs into Picasso, Dali, Man Ray, Luis Bunuel, and T.S. Eliot—and everyone acts precisely according to type. Hemingway speaks in the clear, chiseled prose of his novels and is always angling for a fight; Dali is both charming and bizarre; Picasso is all stormy intensity; Cole Porter is unfailingly witty and urbane. I was, at first, put off by what I took to be a rather cartoonish evocation of these figures, but I then surmised that Woody Allen is exposing (and mocking) precisely our romanticizing predilection to paint the past in primary colors.

At Gertrude Stein’s salon, Gil meets a young woman, who is currently the mistress of Picasso and who had also had flings with Modigliani and Braques (why not?). As he shares with her his boundless enthusiasm for the Paris of the 1920’s, she registers a certain boredom and sadness. How much better than the present, she says, was the Paris of the belle époque, when Toulouse-Lautrec, Gauguin, Degas, and Van Gogh dominated the artistic scene and when Maxim’s glowed in all of its splendor. Someone from inside Gil’s fantasy world exhibits, in short, the same tendency to denigrate the present and romanticize the past, to live somewhere other than in the now.

In a sort of dream-within-a-dream sequence, Gil and his girlfriend are transported from the ’20s back to the Maxim’s of the belle époque where they meet Toulouse-Lautrec and Gauguin, who wax nostalgically about Renaissance! The grass, it seems, is always greener on the other side of the temporal divide between now and “back then.”

The point seems to be that fantasizing about the past is, psychologically and spiritually, a non-starter, for the only time that is fully real is the present. And in this, Woody Allen makes common cause with many of the great spiritual teachers, who have warned about the dangers of living so thoroughly in the past (or the future) that we miss the opportunity to sink into the dense texture of the here and the now.

His gentle mocking of Gil and his girlfriend is meant as a kind of spiritual exercise: Don’t create fantasies about the past. Realize that the same Hemingway who wrote splendid, crystalline prose was also a tortured man who eventually took his life; realize that the same Scott Fitzgerald who composed some of the most beautiful sentences of the 20th century was also a hopeless alcoholic who died penniless; realize that the same Picasso who was the best painter since Rembrandt was also a shameless abuser of women.

This exercise is not meant to sully the memories of these people; it is meant to remind us that the past was every bit as grubby and ambiguous as the present. Therefore, we should live now; create now; love now; follow the will of God now. For this time, with all of its complexity and darkness, is the time that we have.

At the end of the film, Gil reveals that he got this message. Paris, he says, is always most beautiful in the rain.

Add comment