The map of the City of Angels is a veritable Litany of the Saints.

Nine years ago I had a sort of “asphalt epiphany.” It wasn’t on the “road to Damascus,” but on the streets of Los Angeles, my hometown.

After walking, riding buses, and driving through this sprawling city for more than 20 years, it occurred to me that I live in a city named for a saint (Nuestra Señora de los Angeles, Our Lady of the Angels), which is also blessed by the presence of dozens of streets also named for saints.

Some of these streets, such as Santa Monica and San Vicente Boulevards, are relatively well known, but dozens more, like Santa Clara Street and San Blas Avenue, are tiny and hidden.

“All these saints in Los Angeles,” I thought that day, “All the saints of this city of angels.”

I already knew enough of the cultural foundations here-Spanish, Mexican, and Catholic-to recognize that places were originally named for saints to invoke their protection. By contrast L.A.’s 103 streets named for saints, dating from the late 19th and 20th centuries, were named largely by real estate developers with scant knowledge of or interest in the origins and meanings of these names.

Yet each harkened back to the life and story of a saint. What, I wondered, would St. Julian think about life on San Julian Street? How would St. Isidore the Laborer fit into his namesake drive in posh Bel-Air? Would St. Clare see herself in today’s Santa Clara Street? More importantly, could I discern her on, or in, her street?

With questions like these in mind I set off on a poetic road trip through L.A., trying to find the convergence between the saints, the streets, and our lives today. Doing so helped me to strive, however falteringly, to see the sacred in everyone. Perhaps if we recognize that the saints were fallible humans like us, we can see that the fallible humans around us also possess some of the saints’ essence.

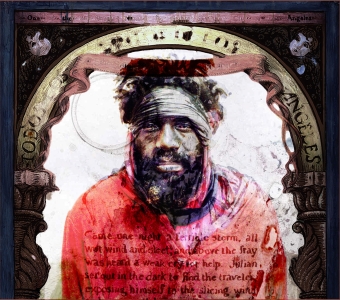

San Julian Street

San Julian Street dates from the 1880s, when the area was part of early Los Angeles’ burgeoning commercial district. Over the past quarter century, San Julian has become the central gathering place for the city’s homeless. Indeed, until recently, its sidewalks were dense with people both day and night, as cardboard scraps and torn plastic tarps marked makeshift sleeping quarters. Most of San Julian’s buildings are missions, drop-in shelters, and single-room-occupancy hotels, serving the indigent population.

This concentration of so much palpable loss and deadened pain on a few city blocks-from Fifth Street to Eighth Street-presents an inexorable challenge. But in the light of the legend of St. Julian the Hospitaller, hope can be found.

Julian, the son of noble parents, was struck by a curse he tried his best to avert. A feeling of doom and hopelessness enveloped Julian, and he wandered the land for years, until one day he settled down beside a road, built himself a shelter, and regained a sense of purpose by providing food and shelter to other wanderers. If Julian is not the official patron saint of both the homeless and those who care for them, he is certainly their patron saint in spirit and story.

And on San Julian Street his tale resonates profoundly in the lived experience of those who walk, work, and live here. Indeed, in one of the clinics I visited, Lamp, many of the employees were themselves-like St. Julian-former wanderers, and considered those they served neither their clients nor their patients but their guests. And these homeless guests offered to pose for my paintings of San Julian Street.

Depicting the homeless as iconic portraits of the saint affords us the opportunity to view them in a new and hallowed light. Just as Julian was a “mere” wanderer for many years, lost and scorned, so, too, the homeless among us are simply at a stage of their journey. If provided the support and care they deserve, they may undergo the same transformation that lifted Julian into the ranks of the canonized-which is to say, they may turn around and lend someone a helping hand.

Santa Clara Street

I located Santa Clara Street on the map and drove to the southeastern edge of downtown, a largely abandoned section of industrial L.A., to seek St. Clare’s spirit. Hers is a short street (not quite two blocks long) and so nearly hidden that one could easily miss it. If found, little would recommend a prolonged visit. Truck dust and dumpsters, razor wire, iron bars, and anonymous doorways are its salient characteristics.

One wonders, is this any way to honor such an important saint, the founder of the Poor Clares?

And then the answer swiftly comes: Yes! It is perfect-on the saint’s humble terms. This unassuming, nondescript sliver of asphalt exudes St. Clare’s humility and the privilege of poverty she sought.

In portraying Santa Clara Street, I used a young friend as my model, Natalie, who struggled with cystic fibrosis. Her bright and positive demeanor in the face of such great challenges mirrored, for me, the light of St. Clare.

Natalie was delighted and inspired to see herself as Santa Clara; and her school hung a print of the piece in its library, in tribute to Natalie’s valiant struggles through the dark days of her illness.

Natalie passed away several years later, but her painted image remains, sustaining her memory and reminding us how many people cope with disease and darkness.

San Ysidro Drive

Half the city and a world away from Skid Row, San Ysidro Drive courses the hills of the upscale community of Bel-Air, neighbor to famed Beverly Hills. Bel-Air was developed by Alphonzo Bell in the 1920s after he struck oil. While enjoying a tour of Europe, Bell jotted down the romantic-sounding names of villages he encountered as names for his streets. Among them was San Ysidro, named for St. Isidore the Laborer.

Isidore was a poor Spanish farmer who worked for wealthy landowners to support his family. How, I wondered, might he relate to Bel-Air? But when I drove along his street, admiring the attractive lawns and gardens, the only people I saw were Latino day-laborers and gardeners-his cultural heirs. Engaging in conversation with one of these gardeners, I asked if he knew for whom the street was named. “Of course,” he replied, “San Ysidro Labrador.”

I considered him, in effect, a contemporary San Ysidro, and asked if he would be willing to pose for me.

“Like this?” he asked, indicating his soiled work shirt and slacks. And thus I portrayed him, a rake in his rugged hand like a nobleman’s scepter, in homage to workers everywhere, in celebration of the dignity of manual labor.

It occurred to me subsequently that we are surrounded by the sons and daughters of San Ysidro. They stoop in the sun to pick our lettuce and strawberries; they pull heavy loads off pickup trucks to build and repair our houses; they clean our offices while we sleep; they take the emptied plates from our tables and wash them in our restaurants; and they watch our children and wash our clothes while we go about our lives.

And they carry a spark of St. Isidore’s essence.

Santa Ynez Street

On Skid Row I also met and photographed a young woman of striking beauty: Jevona, a homeless woman beset by difficulties and continually harassed by men. After I met Jevona, I noticed that the next street named for a female saint I needed to portray was Santa Ynez Street, named for St. Agnes, one of the so-called virgin martyrs.

Like Jevona, Agnes was pursued by men for her looks and subjected to great cruelty. I used Jevona’s face to portray the saint. When I shared my painting with Jevona, she said it made her think of grace.

And it helped me to recognize that for many people-whether homeless, harassed, ill (or helping a loved one who is), or in any of a number of life’s difficulties-just getting through the day can be miracle enough.

Add comment