One night in 1967, Marcelino Ramos entered the United States illegally in the trunk of a car. Crammed with him as the smuggler's car crossed the border without incident from Tijuana, Mexico were his wife, María, his 7-year-old son, Humberto, and his 5-year-old daughter, Rosa. It is the heat that Humberto, now the assistant director of Hispanic ministry for the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, most remembers.

"I always tell people that I am a wetback, not from swimming the river but because I was wet with sweat."

The Ramos family is among those immigrants whom Jesuit Father Allan Figueroa Deck, a leading authority on Hispanic ministry, classifies as "the second wave": the millions from Latin America and from the Asian Pacific region who have come to the U.S. since World War II. Though they are not the "teeming masses" who arrived in the 19th and 20th centuries, they are like the millions of immigrants who, from colonial days, have revitalized the Catholic Church in this country. They arrived poor but hardworking-and filled with an indomitable faith in God and in their own possibilities.

Those qualities can be seen in the success of the 10 children of Marcelino and Maria Ramos. Sergio is a Norbertine priest; Hector, a physician; Rosa, a city corrections officer; Ricardo, an architect; Ramiro, a state corrections officer; Jaime, a doctoral candidate in economics; Estella, a psychologist; Gloria, a teacher with a master's degree from Harvard; and Lorena, still in college.

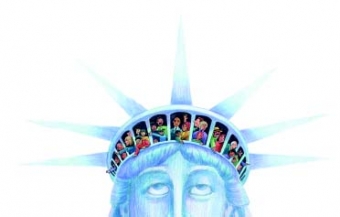

Encuentro 2000, the U.S. bishops' official Jubilee Year celebration held in July, invited the "many faces in God's house"-whites, blacks, Asians, Native Americans, and all shades in between-"to come together to cherish the histories of all our peoples and discover Christ in each other's stories, so that in solidarity we may cross into the new millennium."

The history of the Catholic Church in the United States is one of immigrant people creating a new spiritual home for themselves while seeking to maintain links to their religious traditions. It is the story of outsiders becoming insiders and then failing to welcome those who come after them, a process that repeats itself again and again with each succeeding group. It is the slow, often painful, process of coping with diversity.

Religion has always been important for the peoples of the Americas, whether they arrived 30 or 30,000 years ago. Deck wrote that the most notable feature of the Mesoamerican world was the importance given religion in every sphere of life. Native American reverence for the earth and its ecology has become an important element of modern-day theology. For Christopher Columbus, Hernán Cortés, or John Calvert-the Catholic founder of the Maryland colony-planting the faith went hand-in-hand with exploration, conquest, or settlement. Missioners from various nations left a beautiful saga of dedication, bravery, sacrifice, and martyrdom.

Perhaps because of all these influences, and irrespective of country of origin, Americans take their religion more seriously than do the inhabitants of their motherlands. The Ramoses knelt down every night as a family to pray the rosary. In 1913, Japanese immigrant Leo Hatekeyama went all over Los Angeles looking for a priest who spoke Japanese to hear his Confession. Finding none, he wrote to the bishop of Japan asking permission to send his Confession by registered mail, and to receive absolution and penance by the same means. As a result, Japanese missions were begun in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Seattle.

Whether they came to New Mexico in 1598 or to the East Coast 200 years later, immigrants organized around their religion. Parishes were the center of religious, social, and even political activity. In the former 13 colonies, immigrants organized national parishes, often led by priests who came with them from the mother country. Historian Jay Dolan writes that the church building itself was so important to an Irish neighborhood in Detroit in the 1850s that, when the population began to shift, they "jacked up the building and rolled it 15 blocks northwest."

Similarly, Marcelino Ramos, being too poor to buy a car-even by working as a janitor by night and a gardener by day, rented a two-room house five blocks from a parish church in San Gabriel, California. He led his family there every Saturday for Confession and every Sunday for Mass. "The church represents a familiar institution [for Hispanic immigrants]," writes Deck. "It is one of the few with which they can identify in an otherwise inhospitable land."

In 1820, Catholics were the smallest denomination in the United States, with only 195,000 members. By 1860, they were the largest, with 3.1 million members. The churches had increased from 124 to 2,385 and the number of clergy from 150 to 2,235. Fed by wave upon wave of immigrants-mainly Irish and German-Catholicism had gone a long way toward becoming the church of immigrants, says Dolan.

Immigrants identified their religion with their native culture, customs, and language. The Germans, who by 1860 numbered 50,000 and occupied one of every four Catholic churches in the United States, had the slogan: "Language saves faith." A priest said it was fine to learn English because it was needed to count dollars. But he added that "in German you speak with your children, your confessor, and your God." In San Francisco, where in 1856 the French had their own parish, Notre Dame de Victoires, a local historian described it as "a place where the soft sounds of French are spoken, where friends can gather, and where the customs are familiar." Italians, Czechs, and Slavs, who came later, shared similar values.

By the end of the 19th century, however, the Catholic population had increased to the point where Protestants were concerned about a papist takeover. Out of that concern came the Know-Nothing political party, whose platform was explicitly antiforeign and anti-Catholic. To the nativist mind, Catholics could not be good Americans because of their religion and foreign birth. The nativists feared that in being loyal to the pope, Catholics could not be completely loyal U.S. citizens.

Orestes Brownson, in an 1884 essay titled "Native Americanism," wrote that the Irish and all other immigrants "must ultimately lose their own nationality and become assimilated in general character to the Anglo-American race." A convert, he insisted that a person could be both a good American and a good Catholic.

To counter anti-Catholic prejudice, the bishops promoted Americanization. "What I mean by Americanization is the filling of the heart with love for America and her institutions," said Archbishop John Ireland of St. Paul, Minnesota. "It is the harmonizing of ourselves to our surroundings, so that we will be as to the manner born, and not as strangers in a strange land, caring but slightly for it, and entitled to receive from it but meager favor. It is the knowing of the language of the land and failing in nothing to prove our attachment to our laws and our willingness to adapt, as dutiful citizens, all that is good and lovable in its social life and civilization."

Because immigrants then-as now-were loyal and patriotic, love of the new homeland and the desire to obey its laws were not the issue. As Dolan says: "People were not arguing about such accidental issues as dress, social behavior, or proper speech but about sensitive issues of how to pray, how to worship, and how to educate their children; in other words, passing on a cultural heritage that had been passed on in families for generations and was a vital link both within the past (their family) and the present (their God)."

The Germans, who at first led the opposition to Americanization, ultimately became advocates. By 1916 Chicago Archbishop George Mundelein, a third-generation German, was a leading proponent of Americanization. He opposed national parishes for Poles and Mexicans, who were just beginning to arrive in large numbers to the Chicago area. Mundelein also ordered the Catholic parochial schools to teach only in English. "There is hardly an institution here in the country that does so much to bring about a sure, safe, and sane Americanization of immigrant peoples as do our parochial schools," he wrote to Theodore Roosevelt.

Americanization helped to create a church with an Irish identity. Early on, the Irish gained control in every section of the country and, by the end of the 19th century, two thirds of the bishops were Irish. Germans, Poles, and, more recently, Hispanics fought-with meager success-for more bishops. Appeals to Rome had little effect. Even in St. Louis, where German clergy were in the majority, all but one of the 12 priests elevated to bishop between 1854 and 1922 were of Irish birth or descent. Only about 15 Polish priests were ordained bishop in the 70 years after a protest to Rome led to the appointment of Paul Rhode as auxiliary in the Archdiocese of Chicago in 1908. Mexican Americans in the Southwest, territory seized by the United States from Mexico in 1846, waited 124 years before one of their own priests, Patricio Flores, was ordained a bishop in 1970.

Worse, as the first groups assimilated, they rejected those who came after them. When Italians began to arrive in St. Paul, Minnesota toward the end of the 19th century, Archbishop Ireland invited Father Nicola Carlo Odone from Genoa to take charge of the Catholic mission in St. Paul. For several years the Italians worshiped in the dark, humid basement of the cathedral. It was a humiliating experience for "we children of Catholic Italy," bemoaned Odone, "to have to meet under the feet of a different people [the Irish] which looks at us from above with contempt."

Half a century later, Puerto Rican leader Encarnación Armas complained that Puerto Ricans in New York were forced to worship in the basement and that they had to file through the alley to get there. In New Jersey, Puerto Ricans in one parish had to worship in a chicken house. Mexicans in Texas, as blacks everywhere in the South, had separate churches or chapels. In San Francisco, historian Jeffrey Burns reported "intense racial prejudice and hatred of Asians." A pastor said, "Americans will leave if a Japanese comes in their pew." Blacks were not welcomed in white parishes when, in well-meaning efforts to end segregation, the bishops closed the separate black churches. Now, however, those who were rejected fill the churches, though not at the same time as those who assimilated long ago.

In the interim, cultural pluralism has flourished. The civil-rights movement of the 1960s raised awareness about the importance of ethnic identity and pride. Court decisions and civil-rights laws defended the rights of minorities. All that was part of a wider movement. Karl Rahner wrote that Vatican II was the beginning of a "world church" equally at home everywhere, as Asian and African in its self-understanding as it is European. Tolerance for diversity increased.

Furthermore, Catholic loyalty to the nation was no longer in doubt. Recent immigrants have found it easier to maintain their culture, and some of those who had assimilated reclaimed their heritage. The church has made greater efforts to serve the special needs of newcomers. The Archdiocese of New York alone has sent hundreds of priests to Puerto Rico to learn Spanish, now required in many seminaries.

As a result, ethnic Catholicism flourishes as never before. The rejected have found a home. The Puerto Ricans who worshiped in the chicken house are now in the main church. In St. Ann Parish in Ossining, New York, the Mass is celebrated each week in English, Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian. It is celebrated in 52 languages in the Archdiocese of Newark, says Sister María Iglesias, S.C., Hispanic RENEW Coordinator for New Jersey-based RENEW International. The Mass is celebrated in more than 40 languages in Los Angeles.

The melting pot church is giving way to a multicultural model in which Hispanics will soon be the majority. Hispanic bishops are leading the move to embrace the multicultural paradigm. This is entirely fitting, says Alejandro Aguilera-Titus, assistant director of the bishops' Secretariat for Hispanics, "because the blood of many cultures runs in our veins."

Add comment