“Nothing is more practical than finding God, that is, than falling in love in a quite absolute, final way. What you are in love with, what seizes upon your imagination, will affect everything. It will decide what will get you out of bed in the morning, what you do with your evenings, how you will spend your weekends, what you read, who you know, what breaks your heart, and what amazes you with joy and gratitude. Fall in love, stay in love, and it will decide everything.”

—Pedro Arrupe

“Arrupe House,” said the young man answering the phone.

“Oh sorry,” I responded, thinking I had dialed the wrong number. “I wanted the, um, Jesuit novitiate?”

“Yeah,” he said, and I could almost hear him rolling his eyes. “That’s us. Arrupe House.”

Before joining the Jesuits, I hadn’t a clue who Arrupe was, but these days I’m amazed that Pedro Arrupe, the superior general of the Jesuits from 1965 to 1983, isn’t more well known. Not that all Jesuit superior generals should be household names. Rather, Arrupe’s life is so relevant to contemporary believers that many could benefit from knowing his astonishing story.

Born in Spain in 1907, Pedro Arrupe briefly studied medicine before entering the Society of Jesus at 19, having witnessed a miracle at Lourdes. Shortly after his ordination in 1932, he was sent to a parish in Yamaguchi, Japan.

By 1945 Father Arrupe was the Jesuit novice director in Hiroshima, where, on August 6, he witnessed the dropping of the atomic bomb. Using his medical training, Arrupe converted the novitiate into a makeshift hospital and performed simple surgery on the victims.

In 1959 he was appointed superior of the Jesuits in Japan. Six years later he was elected superior general of the Jesuits. He would preside over the Society of Jesus and serve as a polestar for many other religious orders during a period of volcanic change in the Catholic Church.

The Spanish novice director in Japan seemed the perfect man for the job: a person with international experience and vision, a priest who had lived in both the East and West, and a Jesuit who understood that the church’s center of gravity was moving away from Europe and toward Asia and Africa. Arrupe understood the word inculturation long before it became popular.

Don Pedro, as he was affectionately known, was a faithful Christian, a prayerful Jesuit, and a holy priest. And he was funny. When two young American Jesuits passed through Rome en route to India, Arrupe laughed, “It certainly costs us a lot of money to teach our men about the poor!”

Arrupe was best known for his initiatives on behalf of the poor, urging the Society of Jesus to promote what became known as the “faith that does justice.” In response to the Second Vatican Council’s call for religious orders to return to the vision of their founders, Arrupe sent Jesuits to work among the poor in Latin American favelas (shanty towns), American inner cities, and the teeming slums of India. In 1980 he founded the Jesuit Refugee Service using simple logic: There are refugees everywhere and there are Jesuits everywhere, he reasoned. Why not bring them together?

He also knew that this work would exact a price. Are we ready, he asked the Jesuits, “to take up this responsibility and to carry it out to its ultimate consequence?” Many Jesuits have been martyred because of their work with the poor.

There was another, unintended consequence. Rumors that his efforts carried the whiff of socialism earned Arrupe the suspicion of some in the Vatican, including, at times, Pope John Paul II. The pope was deeply critical of anything that seemed close to socialism or communism. A loyal son of the church, Arrupe would defend his Jesuits but would also beg some to be more prudent: “Please make it easier for me to defend you!”

My own admiration for Pedro Arrupe centers not simply on what he did, but on who he was. In 1981, at age 74, he suffered an incapacitating stroke and was forced to appoint a temporary successor. Then, in a move widely regarded as a personal rebuke, the pope, still critical of the Jesuits’ social justice activity, replaced Arrupe’s man with his own “delegate,” another Jesuit. Arrupe urged his men to be obedient to the pope’s wishes, and the Jesuits eventually weathered the ecclesiastical storm. Nonetheless it was a crushing blow for the ailing Arrupe, who wept at the news.

During this long illness, which he bore patiently until his death in 1991, Arrupe composed a remarkable prayer, a moving testimony of spiritual surrender. Here Arrupe becomes for me, and for all those who have felt crushed under the weight of suffering, marginalized by their own church, and confused by life’s baffling ways, a ringing testament of faith.

“More than ever,” he wrote, “I find myself in the hands of God. This is what I have wanted all my life, from my youth. But now there is a difference—the initiative is entirely with God. It is indeed a profound experience to know and to feel myself so totally in God’s hands.”

This essay is excerpted from My Life with the Saints (Loyola Press, 2006) by James Marin, S.J.

This article also appears in the April 2007 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 72, No. 4). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

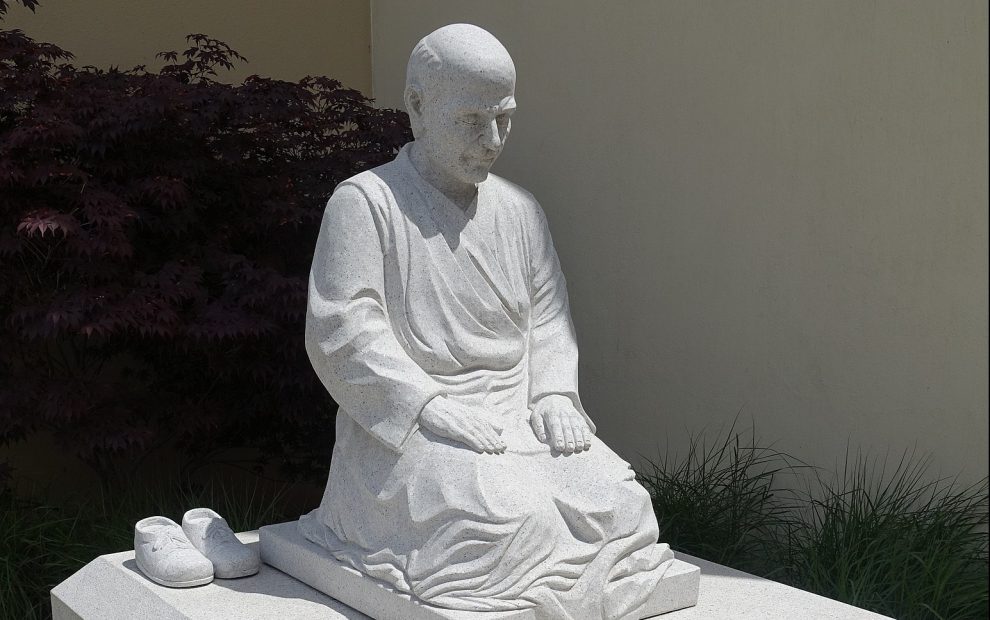

Image: Wikimedia Commons/Daderot

Selected Resources:

Pedro Arrupe: Essential Writings selected by and with an introduction by Kevin Burke, S.J. (Orbis Books, 2004)

One Jesuit’s Spiritual Journey by Pedro Arrupe, S.J. with Jean-Claude Dietsch, S.J. (Institute of Jesuit Sources, 1986)

Justice with Faith Today by Pedro Arrupe, S.J. with Jerome Aixala, S.J. (Institute of Jesuit Sources, 1980)

“More than Ever,” My Life with the Saints by James Martin, S.J. (Loyola Press, 2006)

Add comment