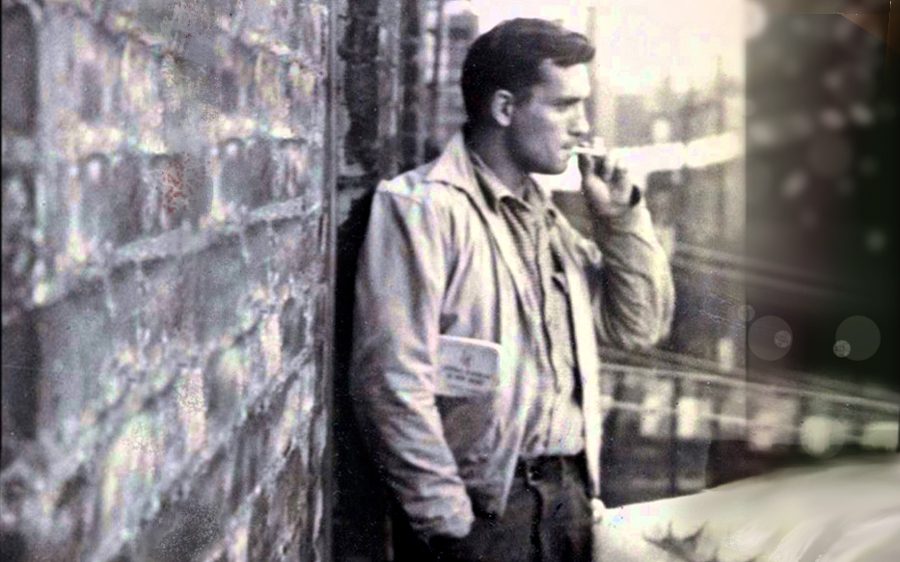

Those more familiar with Jack Kerouac’s dissolute public life than with his literary output may be surprised to see him numbered among Catholic authors. But, like James Joyce, whom Kerouac admired and sometimes imitated, Kerouac’s writing was remarkably informed by his Catholic upbringing.

On the Feast of St. Joseph, 1922, Kerouac was baptized in the basement of the church of St. Louis de France in Lowell, Massachusetts. He later attended the parish elementary school, where the Sisters of the Assumption of the Blessed Mary taught him. He experienced all the events of a Catholic childhood, and in his case these experiences were cast in French Canadian terms. For Penance before his First Communion, he was assigned Notre Peres and Salut Maries.

When he was 5, Kerouac transferred to a grade school run by Canadian Jesuit brothers. For a time the brothers thought they had a vocation, and their impact was so strong on young Jack he often quipped in later life that he was a closet Jesuit.

Youngsters take away from their earliest religious experiences the things that speak most specifically to them. What impressed Jean Louis (Jack) Kerouac were the dark mysteries associated with the Crucifixion and the wages of sin.

These fears became manifest when at age 4, Kerouac witnessed his brother Gerard’s death, funeral, and, on a glum rainy day, his burial. Jack idolized his older brother and attributed to him everything that was good, in contrast to what he saw as his own weak and sinful nature. In his later years he even fantasized that his saintly brother was guiding his hand as he wrote. This conviction that his writing was somehow inspired made Kerouac reluctant to revise and also hypersensitive to criticism.

The Depression-era Lowell in which Kerouac grew up was a city struggling to stay alive. The textile mills were moving to the South where the labor was cheaper. There was a sort of gloom that pervaded everything and reached into the enclaves of the Irish in the Acre section of town, the hard-working Greeks who settled near downtown, the Billerica Poles and the French Canadians who inhabited Moody Street and Pawtucketville. No doubt influenced by his paranoid father, who felt others in the city were out to get the French Canadians, young Jack dreamed of moving elsewhere and becoming a great writer.

Because his friends and family scoffed at this ambition, Jack sought out his parish priest, Father Armand “Spike” Morissette. This priest friend encouraged Kerouac to ignore the naysayers and follow his dream. He advised him to go to New York where he felt his writing would be appreciated and advanced.

Readers of Kerouac’s 30-plus published works will find a wealth of Catholic symbolism.

Advertisement

But Jack had no money to support himself in a distant city. Morissette convinced him a scholarship to college was the only solution. In this his mother concurred.

Several colleges, impressed by Kerouac’s feats on the gridiron, had come calling. Among them was the Jesuit Boston College, which his father’s boss (who did the college’s printing) pushed for. Jack, abetted by his mother, opted for Columbia University in New York where he felt his literary ambitions would be better realized and where his mother figured he might carve out a business career in something like insurance. The New York move cost Kerouac’s father his job.

In order to satisfy some academic deficiencies and to gain some weight for football, Jack enrolled in Horace Mann prep school. Here he felt out of his element, a poor boy among rich kids.

Columbia was different, but Kerouac still felt like an outsider, like Li’l Abner in New York City, as he put it.

But even though he felt at odds with the fast-paced environment that swallowed him up, he soon yielded to the temptations the metropolis provided, allowing himself the forbidden pleasures of sex and alcohol the big city afforded. Eventually he would experiment with everything, adding drugs and homosexual encounters. He struggled in his classes and on the football field. Still, he kept his goal of being a great writer, and his contrition for his lapses was real and constant.

In The Town and the City, Kerouac’s fictional counterpart, Mickie Martin, chastises himself: “What am I doing? Oh Christ, what am I doing to everybody?” He felt guilty for the sacrifices his parents had made so he could attend college.

This guilt followed him everywhere, through his abortive athletic career, his stint in the Merchant Marines during the Second World War, and his Bohemian existence during the days of writing disappointment and infrequent success.

Kerouac’s notion of the root word was beatific, which he described as living the Beatitudes “in a state of joy.”

Advertisement

This guilt was one reason he tried Buddhism, attracted by its First Noble Principle that existence was suffering. He also felt that Zen discipline might free him from his errant habits. At least two of his published works are heavy with Buddhist thought and meditation. At length he confessed that he failed to conquer his growing dependence on alcohol and he drifted away from Zen beliefs he saw as coming to nothing. The memories of his Catholic childhood stayed with him when his The Town and the City finally found a publisher. He fell to his knees in his kitchen and recited a prayer of thanksgiving.

Success came slowly and sporadically, while Kerouac continued to live life on the edge. He is credited with coining the phrase “the Beat Generation,” even though he disavowed the direction the movement took. “I’m no Beatnik,” he averred in a CBS interview with Mike Wallace, “I’m a Catholic.”

Still, he was viewed as the spokesman for a cultural movement that accelerated after the publication of his On the Road. Jack’s own derivation of the word didn’t emphasize the downtrodden, alienated, bongo-drum caricatures popular with dissidents. Kerouac’s notion of the root word was beatific, which he described as living the Beatitudes “in a state of joy.”

His decision to live life boldly, along with his naïve trust of others, contributed to his homosexual episodes, which repelled and haunted him even as he recorded them in his journals and elsewhere.

For years, Kerouac was frequently on the move: New York, California, Lowell, and Florida, to which his beloved mother moved. He spent time in Mexico and Morocco and had a brief sojourn in Paris. The American journeys were collapsed into a single trip in On the Road, which the author states he saw as a pilgrimage with himself as a sort of Christ figure sent to redeem the American soul.

Readers of Kerouac’s 30-plus published works will find a wealth of Catholic symbolism. He meditates before a cross in a dark church and contemplates the tiny crucifix on the gift rosary from his First Communion. He remembers his own home with its abundance of holy pictures and prayer cards, especially those of Saint Therese of Lisieux.

Several of his books also canonize his elder brother Gerard and recount his own childhood fears and terrors when confronted by such Catholic devotions as the outdoor Stations of the Cross set in a sim collection of grottoes near Lowell’s Merrimack River. Kerouac, in Doctor Sax, recounts seeing a dark shape flitting among these stations and the culminating Crucifixion mound.

While I was acquainted with Jack Kerouac only as a fellow member of the Lowell High track team and never guessed at his literary aspirations, I still feel saddened by his slow decline, his transformation into a bloated drunk in the city that once spurned him and now embraced him. His latter presence was a far cry from the Golden Boy I remembered—a shy, talented athlete who made few waves except in sports.

Kerouac died in October 1969, but he had really been dying for a long time. As one of his Mexico City Blues choruses tells us, he long felt he was falling through dark tunnels of hate toward a vision of a radiant eternity.

Many others profited from the short-lived popularity of the Beat Generation and Jack’s manuscripts now fetch healthy sums, but he tasted very little of the rewards of fame while suffering most of its negative aspects.

Kerouac’s plain flat headstone states, “He Honored Life.”

Jack’s wayward journey, which included three marriages, multiple drunken orgies, and other excesses, is easy to condemn. Yet there is much to admire in Kerouac—his joy of living accompanied by a recognition and sorrow for sin. He encountered Christ, as we are encouraged to do, and he also met Satan.

Kerouac’s plain flat headstone states, “He Honored Life.” He was buried at St. Jean Baptiste Church in Lowell, where he once served as an altar boy. His old confidant, Father Morissette, celebrated the Solemn High Requiem Mass, and for the scriptural readings he chose a passage from the Book of Revelation: “They shall rest from their labors, for they will take their works with them.”

There are now other monuments in Lowell commemorating Kerouac. The city has come to terms with its all-too-human native son. We should do no less.

This article also appears in the April 2004 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 69, No. 4, pages 31-33). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Flickr/Geoth

Add comment